Traditions: Separating the Important from the Inconsequential - 2023

There's significant evidence that traditional practices were beneficial and adaptive. But many reject traditions as relics of a barbarous past. How do we make that determination?

I. Cultural Evolution, Traditions, and Cassava

For anyone who has been paying attention, it should be obvious that I get a lot of my material from Scott Alexander of Slate Star Codex.1 Optimistically, I take his ideas and expand upon them in an interesting fashion. Realistically, the relationship is more that of parasite and host. But regardless, I bring it up because I am once again returning to that well. This time, to talk about a 2019 series of posts he did on cultural evolution.

What’s cultural evolution, you ask? Well in brief it’s evolution that works by changing culture, rather than evolution that works by changing genes, but is still evolution working in service of increased survival and reproduction. That this variety of evolution should exist and show up in the form of cultural “traditions” almost goes without saying.

(I put traditions in scare quotes because the elements of cultural evolution can take many forms, out of these some would definitely be called traditions, but others are more properly classified as taboos, habits, beliefs, behaviors and so on. I’ll be using tradition throughout just to keep things simple.)

Some traditions so obviously serve to enhance the survival and reproduction of the people within that culture that their identification is trivial. A blatantly obvious example would be the crafting and wearing of heavy clothing during the winter, a tradition that is present in all northern cultures. The enhanced survival which derives from these sorts of traditions is obvious, but for many if not most people it’s equally obvious that this cannot be said for all traditions. Some traditions are useless, probably silly and potentially harmful. Should we be able to identify these traditions then getting rid of them would carry no long term harmful consequences. As many of the traditions which have been passed down over the years impose significant restrictions on behavior, there has been a lot of argument over which traditions should go into which bucket: which traditions are important and should be preserved, and which are inconsequential and can safely be discarded?

Initially you may be under the impression that it should be fairly obvious which traditions enhance survival and which are meaningless, but one of the key insights contained in Alexander’s posts, an insight based largely on his reading of The Secret of Our Success by Joseph Henrich, is that sometimes it’s not obvious at all. As an example, let me quote Alexander’s quote of Henrich (I told you I was a parasite) as he talks about cassava, or manioc as it’s sometimes known — edible starchy root tuber:

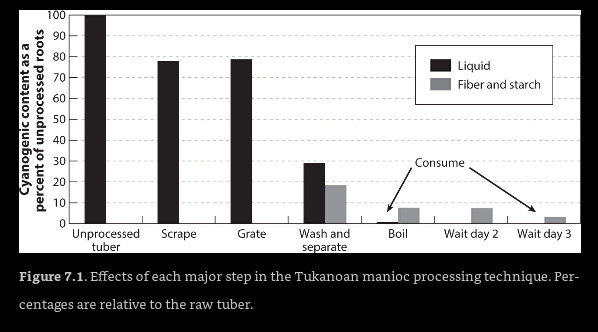

In the Americas, where manioc was first domesticated, societies who have relied on bitter varieties for thousands of years show no evidence of chronic cyanide poisoning. In the Colombian Amazon, for example, indigenous Tukanoans use a multistep, multiday processing technique that involves scraping, grating, and finally washing the roots in order to separate the fiber, starch, and liquid. Once separated, the liquid is boiled into a beverage, but the fiber and starch must then sit for two more days, when they can then be baked and eaten. Figure 7.1 shows the percentage of cyanogenic content in the liquid, fiber, and starch remaining through each major step in this processing.

Such processing techniques are crucial for living in many parts of Amazonia, where other crops are difficult to cultivate and often unproductive. However, despite their utility, one person would have a difficult time figuring out the detoxification technique. Consider the situation from the point of view of the children and adolescents who are learning the techniques. They would have rarely, if ever, seen anyone get cyanide poisoning, because the techniques work. And even if the processing was ineffective, such that cases of goiter (swollen necks) or neurological problems were common, it would still be hard to recognize the link between these chronic health issues and eating manioc. Most people would have eaten manioc for years with no apparent effects. Low cyanogenic varieties are typically boiled, but boiling alone is insufficient to prevent the chronic conditions for bitter varieties. Boiling does, however, remove or reduce the bitter taste and prevent the acute symptoms (e.g., diarrhea, stomach troubles, and vomiting).

So, if one did the common-sense thing and just boiled the high-cyanogenic manioc, everything would seem fine. Since the multistep task of processing manioc is long, arduous, and boring, sticking with it is certainly non-intuitive. Tukanoan women spend about a quarter of their day detoxifying manioc, so this is a costly technique in the short term.

Henrich then goes on to imagine what might happen if someone decided to start questioning traditional methods of manioc preparation.

Now consider what might result if a self-reliant Tukanoan mother decided to drop any seemingly unnecessary steps from the processing of her bitter manioc. She might critically examine the procedure handed down to her from earlier generations and conclude that the goal of the procedure is to remove the bitter taste. She might then experiment with alternative procedures by dropping some of the more labor-intensive or time-consuming steps. She’d find that with a shorter and much less labor-intensive process, she could remove the bitter taste. Adopting this easier protocol, she would have more time for other activities, like caring for her children. Of course, years or decades later her family would begin to develop the symptoms of chronic cyanide poisoning.

Thus, the unwillingness of this mother to take on faith the practices handed down to her from earlier generations would result in sickness and early death for members of her family. Individual learning does not pay here, and intuitions are misleading. The problem is that the steps in this procedure are causally opaque—an individual cannot readily infer their functions, interrelationships, or importance. The causal opacity of many cultural adaptations had a big impact on our psychology.

Henrich then proceeds to examine the almost magical way that cultural evolution works. A slow and steady accretion of knowledge, much like natural evolution where you can’t get where you’re going by straight logical jumps.

Wait. Maybe I’m wrong about manioc processing. Perhaps it’s actually rather easy to individually figure out the detoxification steps for manioc? Fortunately, history has provided a test case. At the beginning of the seventeenth century, the Portuguese transported manioc from South America to West Africa for the first time. They did not, however, transport the age-old indigenous processing protocols or the underlying commitment to using those techniques. Because it is easy to plant and provides high yields in infertile or drought-prone areas, manioc spread rapidly across Africa and became a staple food for many populations. The processing techniques, however, were not readily or consistently regenerated. Even after hundreds of years, chronic cyanide poisoning remains a serious health problem in Africa. Detailed studies of local preparation techniques show that high levels of cyanide often remain and that many individuals carry low levels of cyanide in their blood or urine, which haven’t yet manifested in symptoms. In some places, there’s no processing at all, or sometimes the processing actually increases the cyanogenic content. On the positive side, some African groups have in fact culturally evolved effective processing techniques, but these techniques are spreading only slowly.

I understand that’s a long selection, but there’s a lot going on when you’re talking about cultural evolution and I wanted to make sure we got all of the various aspects out on the table. Also while I’m only going to include the example of cassava/manioc, the modern world offers many examples of similar things happening. It’s always easiest to see with diet where poor choices show up decades later.

II- Applying the Lessons of Cassava to the Question of Traditions in General

To begin with we can see that it’s not easy to tell which traditions are important and which are inconsequential. Accordingly, we should exercise significant humility when we decide whether to put a given tradition into the “survival” or the “silly” bucket. In particular, one of the things which should be obvious is that cause and effect can be separated by a very large gap in time. Now that we have modern techniques for testing the cyanogenic content of something we can identify how much it’s reduced at each step in the manioc preparation process, but that wouldn’t have been clear to the Tukanoans. Rather, they could only go by eventual health effects which could take years to manifest and would be hard to connect when they eventually did end up appearing. As Henrich points out, you would first have to make the connection between someone’s health issues and eating manioc, and then further make the connection to whatever step they had skipped or gotten rid of.

It’s also interesting to note that one component of a tradition can seem to hold most or all of the utility. In the example of the cassava, just boiling it gets rid of all the immediately noticeable issues: it “removes or reduces the bitter taste and prevents the acute symptoms (e.g., diarrhea, stomach troubles, and vomiting).” We can imagine something similar happening with other traditions. Like cassava preparation, lots of traditions come as packages, for example most religions have a whole host of prohibitions and injunctions related to sex. And you can imagine someone saying, “oh what they’re really worried about is STIs and unplanned pregnancies, now that we’ve invented latex condoms, we don’t have to worry about any of the injunctions against extramarital sex. We’ve identified the bit that affected survival and now the rest of it is just silly.” But all of this might be the same as someone deciding that boiling was the only tradition necessary to make cassava safe, and deciding all other steps were superfluous. When, in reality, the benefits of the other steps are just as important, but more subtle.

Finally, there’s Henrich’s point that traditions, and the benefits they provide, are often non-intuitive. Alexander even goes so far as to speculate, in his commentary, that trying to use reason to determine which traditions are important could actually take you farther away from the correct answer, at least in the near term. And this is one of the chief difficulties we encounter when grappling with our central question. How do we decide if a tradition can be safely discarded? When we’re looking for evidence of whether something confers an advantage to survival and reproduction, how long of a time horizon do we need to consider? Henrich points out with cassava that it would take several years before the health problems from improper preparation were even noticeable. How much longer after that would it take before people were able to make the connection between the problems and the tradition they’d eliminated? Remember, even hundreds of years after its introduction into Africa, cyanide poisoning is still a serious health problem. The fact that the Africans never had certain traditions of preparation to begin with makes things harder, but you’re still looking at an awfully long time during which culture hasn’t absorbed a connection between cause and effect.

It seems entirely possible that even if you were being very rational, and very careful about collecting data, that it might, nevertheless, take multiple generations, all building on one another, before you could make the connection between the harm being prevented by a tradition and the tradition itself. Certainly it appears to take numerous generations to come up with the traditions in the first place.

To sum it all up, when attempting to determine which traditions are important, you’re going to encounter numerous difficulties. Chief among them is the enormous amount of time it’s going to take before you can say anything for certain. And during this time, when you are trying to make a determination, much of the evidence is going to point in the wrong direction. In particular there seems to be a recent bias towards dismissing traditions as unimportant. This is assisted by the fact that technology has done quite a bit to alleviate some of the perceived harms. We’ve already discussed our ability to detect the cyanide remaining at various points in the preparation of cassava. On the other hand it might do the opposite. Technology might lead us to giving undue weight to sources of harm or benefit which are easy to detect. Something of a streetlight effect.

As I mentioned at the beginning there’s been a lot of arguing over this question of which traditions are important and which are inconsequential. To be fair, this argument has been going on for a long time, at least the last several hundred years and probably even longer, but I would argue that it’s accelerated considerably over the last few decades. In particular three things seemed to have changed recently:

First, support for traditional religion has gone into a nosedive. There are, of course, various statistics showing the percent of believers (in the US) going from 83 to 77 between 2007 and 2014 and the number of unbelievers rising by a nearly identical amount, and this may not seem like that big of a deal. But it’s important to note how quickly that decline happened. Also it’s almost certainly gotten worse since then, nor did the pandemic help. But more importantly as it relates to this topic, even if 77% of people are still religious, the definition of “religious” has been changing. Things like premarital sex barely raise an eyebrow. Female ordination has been common for decades in many Christian denominations even while it still provokes fights in others. Beyond significant changes at the level of the organization, the abandonment of many religious principles has been even greater at the individual level.

Second, technology has made it easier to work around traditions. For one, survival is no longer a concern for most people, meaning that traditions which increased survival, particularly in the near term, are no longer necessary. As another example, in the past, traditional gender roles were hard to subvert due to the lack of birth control, but now we can go so far as to medically transition people from one sex to another, at least superficially. The list could go on and on, and while I’m sure that in some cases the fact that technology can subvert tradition means that it should, I don’t think that’s clear in all cases.

And finally, perhaps following from the first two points, or perhaps causing them, progressive ideology appears to come with a hostility to many traditions already baked in, particularly those traditions seen to impinge on individual autonomy.

Pulling all of this together once again brings us to our original question: Which traditions can be dispensed with? Increasingly the answer is “Most of them!” Perhaps people are correct about this. Maybe we have ended up with a bunch of silly traditions which need to be gotten rid of, but if we can take anything from the lesson of cassava, it’s going to take a long time to be sure of that, and reason isn’t necessarily going to be of much help.

If, in fact, the normal methods of collecting and evaluating evidence in a scientific manner take too long to operate effectively with respect to traditions, you might be wondering what other tools we have for deciding this question? I would submit four for your consideration (there may be others):

1- The duration of the tradition. How long has it been around?

2- The strength of enforcement for the tradition. Historically, how severe were the penalties for violating it?

3- The frequency of the tradition among the various cultures. How widespread is it? Is it present in many different cultures?

4- The domain of the tradition. Does the tradition relate to something which could impact survival or reproduction? For example the traditional method of cassava preparation related to the staple crop for most of those who ate it, and there are many taboos and traditions around sex.

To the above I would add one other consideration which doesn’t necessarily speak to the intrinsic value of any given tradition, but might suggest to us another method for choosing whether to keep or discard it.

5- The difficulty of maintaining the tradition. This speaks to the issue of tradeoffs. How costly is it to keep the tradition? How much time are we potentially wasting? What are the downsides of continuing as is? Reversing things, if we abandon the tradition what are the potential consequences? Is there any possibility of something catastrophic happening? Even if the actual probability is relatively low?

You might recognize this as a very Talebian way of thinking, and indeed he’s a pretty strong defender of traditions. He would probably go even farther at this point and declare that traditions must be either robust or antifragile, otherwise they’re fragile and would have “broken” long ago, but I spent a previous post going down that road, and at the moment I want to focus on other aspects of the argument.

III- An Example of a Recently Discarded Taboo

Enough of generalities, starchy tubers and Taleb! It’s time to take the tools we’ve assembled and apply them to a current debate. In order to really test the limits of things we should take a tradition that has recently been declared to be not just inconsequential and irrelevant but downright harmful and malicious. With these criteria in mind I think the historical taboo against Same Sex Marriage (SSM), a taboo that has recently been decisively repudiated, is an excellent candidate.

Before we begin I want to clarify a few things. First it is obvious that historically gay individuals have been treated horribly. And I am by no means advocating that we should return to that. Honestly, I really hope that traditions and taboos around homosexuality and SSM can be discarded and that nothing bad will happen, but I can’t shake the feeling that these traditions and taboos were there for a reason. Also given that 71% of Americans support SSM, not only is this a great tradition to use as an example for all of the above, it’s also very unlikely that anything I or anyone else says will change things. Finally my impression is that many people offer up homosexuality and SSM as the gold standard for where reason came up with the right answer and tradition came up with the wrong answer. All this makes it a great place to start.

One of the key arguments in the broader discussion is that past individuals did things based on irrational biases, but now that we’re more rational, and can look at things in the cold light of reason, we can eliminate those biases and do the correct thing rather than the superstitious thing. But considered rationally, what is the basis for SSM?

(I should mention I’m mostly going to restrict myself to the narrower question of SSM, as opposed to tackling the issue of homosexuality more broadly.)

Don’t get me wrong, I understand the moral argument in favor of SSM, and it’s a powerful one, but I’m not sure I understand the argument from reason.

As has been long remarked upon, homosexuality does not make a lot of sense from an evolutionary perspective, which is not to say that people haven’t tried. Taking something that already doesn’t make sense and slapping the sanction of the state on it with SSM, if anything just makes it worse by giving gays even less incentive to reproduce. So while it’s entirely possible to make a moral argument for the practice, reason doesn’t seem to play much of a role.

Moving beyond that, most SSM proponents seem to argue that its legalization harms no one. That it’s not only immoral to withhold marriage from individuals who want it, but that it doesn’t inconvenience anyone else to give them this right. Here’s where I think the question of time horizons brought up by Henrich is particularly salient. He offers plenty of examples of traditions where the harm prevented by the tradition will only manifest many years later. And even without those examples, I think the idea that it could take a generation or two for certain kinds of harm to manifest and that the connection between cause and effect might not be clear even when it does, is entirely reasonable. (There’s that word again.) To put it another way, it's impossible to know how long it takes for something to manifest, or to be entirely sure that we have “waited long enough”. As a reminder, Obergefell just barely had its eighth anniversary. That ***definitely*** does not seem like long enough to draw a firm, and final conclusion.

To return to my parasitism, Alexander just barely posted2 about one explanation for the more general category of all sexual purity taboos (including homosexuality) and that’s to prevent the spread of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). A couple of selections:

STIs were a bigger problem in the past than most people think. Things got especially bad after the rise of syphilis: British studies find an urban syphilis rate of 8-10% from the 1700s to the early 1900s. At the time the condition was incurable, and progressed to insanity and death in about a quarter of patients.

[T]he AIDS epidemic proves that STIs transmitted primarily through homosexual contact can be real and deadly. Men who have sex with men are also forty times more likely to get syphilis and about three times more likely to get gonorrhea (though they may be less likely to get other conditions like chlamydia).

In the previous thread, some people suggested that this could be an effect of stigma, where gays are afraid to get medical care, or where laws against gay marriage cause gays to have more partners. But Glick et al find that the biology of anal sex “would result in significant disparities in HIV rates between MSM and heterosexuals even if both populations had similar numbers of sex partners, frequency of sex, and condom use levels”.

This is probably part of the explanation for the taboo, and I would direct you to Alexander’s post if you want more detail. For my part I worry that uncovering the STI link is akin to finding out that boiling cassava “remove[s] or reduce[s] the bitter taste and prevent[s] the acute symptoms (e.g., diarrhea, stomach troubles, and vomiting)”. That in both cases it will lead someone to feel that they have uncovered everything they need to know about the reason for the taboo. That in the same way they might decide other parts of the cassava preparation tradition are unnecessary, they might also decide that if we have other ways of avoiding STIs that there’s no need to continue to worry about taboos around sexual purity either. It is true since I’m trying (somewhat unsuccessfully) to restrict discussion to SSM rather than homosexuality more broadly, that this point doesn’t apply. The question is does the recognition of same sex unions increase promiscuity in this area or does it decrease it?

Thus far, while I’ve offered some evidence for the case that the taboo against SSM and homosexuality more broadly probably increased our survival, we’re a long way from reaching a definitive answer. Also, we still have to grapple with the role that technology plays in this discussion. In other words we have yet to conclusively answer whether we should continue to observe these taboos, or whether, in the modern era, we should dispense with them.

Having examined the ways in which Henrich’s book might help, let’s turn to the standards I suggested:

1- The duration of the tradition. How long has it been around?

I’m not an expert on historical homosexuality, but it seems pretty clear that taboos against SSM have been around in one form or another for all of recorded history. Wikipedia’s Timeline of Same Sex Marriage dedicates 4% of its space to everything before 1970, and the other 96% to stuff that happened after 1970. So yes, it wasn’t entirely unknown, but there was definitely a taboo against it at every historical point you care to imagine.

2- The strength of enforcement for the tradition. How severe are the penalties for going against it?

Historically punishments for homosexuality have been severe. I assume that, at least on this point, I won’t get much of an argument from anyone. Though it is true that the most severe punishments seem to have been in Europe and the Middle East, severe punishment wasn’t limited to those areas either. Where the taboo existed (nearly everywhere) it was very strong. And even in times and places where the taboo against homosexuality was not particularly extreme it was still strong enough that it was extraordinarily rare for people to be in a position to confront the, yet further still taboo, against SSM.

3- The frequency of the tradition among the various cultures. How widespread is it? Is it present in many different cultures?

As I mentioned, a taboo against SSM was basically present at all times throughout human history, but it’s clear that further it was present in nearly all places as well. It should be noted that even today 75% of the world’s population still lives in countries where it’s illegal.

At this point if I were on the other side of that argument (and I am, a little bit, but it’s also apparent that that side doesn’t need any help) then I would use the ubiquity of the taboo to argue that it’s not cultural, it’s technological. It’s not that everyone had the same culture, it’s that everyone still had the same, relatively primitive, technology. I’m not sure current technology makes as big of a difference to this sort of thing as we think, but there's at least an interesting discussion to be had on the topic.

4- The domain of the tradition. Is the tradition related to something which could impact survival or reproduction?

I would argue that this is the point that most people overlook or at the very least minimize. If culture evolves to enhance survival, then you would expect a lot of what comes out of cultural evolution to involve things which directly impact not only survival but reproduction, since that’s what you’re selecting for. Meaning that, when you’re trying to decide whether a given tradition is important or not, asking whether it has any impact on those two things would be a good place to start. And clearly the traditions we’re talking about do. Up until the very recent past there were a lot of people who were born who otherwise wouldn’t have been, had there been no taboos. Anecdotally, I have four cousin in-laws who wouldn’t have existed if Stonewall had happened 20 years earlier. Which is to say, my wife's uncle would have never gotten married and had children if the taboos hadn't existed.

5- The difficulty of maintaining the tradition. This speaks to the issue of tradeoffs. How costly is it to keep the tradition? How much time are we potentially wasting? What are the downsides of continuing as is? Reversing things, if we abandon the tradition what are the potential consequences? Is there any possibility of something catastrophic happening? Even if the actual probability is relatively low?

I’ve been conflating and separating SSM from other taboos against homosexuality more or less as it suits me, and with, admittedly, less rigor than would be ideal, but when it comes to the issue of trade offs this distinction is very important.

In terms of behavior, SSM doesn’t allow or deny anything that isn’t covered by general taboos against homosexuality, but from the standpoint of what might be called “respectability” it’s very different. With most taboos, there are always going to be significant violations that end up being overlooked. Where you might say an “understanding” exists. For homosexuality, this was the era of “Don’t Ask. Don’t Tell.” But when it moves from being decriminalized to legal, to sanctioned (which is the role SSM plays for homosexuality) we have not merely overlooked that taboo, we have essentially inverted it. That the Rubicon we’re crossing (for good or ill) is not in what behaviors we overlook, but in what behaviors we celebrate.

For we are indeed crossing a Rubicon, and there would appear to be a lot of things indicating that this crossing is not inconsequential. For reasons of charity, I hope I’m wrong about this, but also because I don’t see any chance of things reversing themselves, if my fears are proven legitimate, and we are headed for a bad outcome. There is some chance I’m right about the role of these traditions, that they were important, but recent technology has rendered them inconsequential. But given all of the above, I think the entire issue should be approached with more humility.

In the end I keep coming back to a point I’ve made in the past. You have two options: You can assume that the vast majority of people in the vast majority of places throughout all of history down to the present day were hateful, irrational bigots, or you can assume that maybe somewhere in all of this that there was some wisdom, and we should attempt to understand what that wisdom was before we abandon it.

Some additional thoughts in 2023:

I remember a quote from Ross Douthat that I can’t seem to find. But basically he said that: If a conservative had claimed back in 2015 that the legalization of SSM would be followed in less than 10 years by a doubling in the number of youth who identify as transgender, huge fights over puberty blockers and other interventions for those same youth, along with all the other culture war fights we’ve seen — they would have been labeled as an extreme reactionary fear-monger. And yet, that’s precisely what’s happened…

I think the idea that we’ve crossed a Rubicon of some sort has held up rather well…

If you’re also following my Patheos blog you’ll notice quite a bit of overlap between this Substack post and the two Patheos posts which bracket it — the last one and the next one. I debated doing something different, but I thought it might be interesting to see the issue from a bunch of different angles. Oh, and there’s the fact that I’m lazy, that also played a role. If you’re interested in encouraging me to be less lazy, consider donating.

That’s what it was in 2019, and that’s what it will always be in my heart, but currently he blogs at Astral Codex Ten.

The “just barely posted” happened in 2019, but I’m leaving the wording in because it’s important to recognize that it came up in the middle of my writing.