The Everest Fallacy

A method for making better decisions should you ever find yourself in Kathmandu, or paying for SEO, or hoping to see the Supreme Court.

Many years ago, my grandmother took a trip to India and Nepal. While in Kathmandu, she had the opportunity to take a helicopter ride to see Everest. As I recall, the ride was $80. She decided against it, feeling that $80 (or however much it cost1) was too expensive.

Upon her return, she mentioned this to my father. He pointed out, if you live in Utah, the cost to see Everest is thousands and thousands of dollars. She just refused to pay the last $80. When framed that way, my grandmother realized that she had made a mistake.

Despite occurring decades ago, this anecdote has always stuck with me. It seemed to point to a broader lesson—a mental framework that might help with certain kinds of decisions. A paradigm which could be applied to areas and endeavors beyond helicopter rides to the world's highest peak.

I’ve taken to calling it the Everest Fallacy. I’m not sure whether it’s a true fallacy, something that belongs on the official “List of Fallacies”.

Despite this, I’ve found it to be very clarifying in a number of different situations. Consequently I thought it was worth passing along. Had my grandmother been aware of it she probably would have taken that ride. And once you’re aware of it perhaps you’ll make different, and ultimately better decisions as well.

Though I’ve carried this around in my head for a long time, I recently came across a situation where it seemed particularly pertinent.

My company has been working with a search engine optimization (SEO) firm. For those unfamiliar with the endeavor, everyone wants to get leads from their website—it’s why you have a website. But before that can happen people need to be able to find your website. And by find, I mean it needs to show up in the top two or three results. Every SEO provider promises this outcome, but if they promise it will be cheap or easy they’re lying. There’s a lot of competition for those spots, and it’s going to take awhile to rise from obscurity to authority. The Google algorithm needs to be wooed. (She’s both fickle and mercurial.)

When I started the process, I talked to at least half a dozen providers. All of them came highly recommended by people I knew personally. People who’d used them and gotten good results. I did independent research on top of that and felt like I’d done everything in my power to pick a solid and competent firm. Despite all this, the SEO firm has been at it for 20 months, and I’ve gotten—if I’m generous—two leads. In the meantime I’ve spent tens thousands of dollars. That’s a truly awful price to pay per lead. But every month, my search engine position has gone up on the terms I care about. Am I just a few months from a #1 position and a steady supply of leads? If I cancel it now will I be falling prey to the Everest Fallacy? Having travelled all the way to Kathmandu, but balking at the helicopter ride?

Some may feel that this situation doesn’t belong in the same bucket as my grandmother’s. My grandmother knew that if she spent $80, she'd almost certainly get to see Everest. As opposed to this, I don’t know what will happen if I keep spending money on SEO. From this perspective her mistake seems straightforward, my mistake far less so. It could very well be a mistake to spend another dime on SEO.

I would argue that it’s more a difference of degree than of kind. I’m sure that uncertainty played a strong part in my grandmother’s decision not to take that helicopter ride. Perhaps they’d get close and it would turn out that Everest was completely covered by clouds. Maybe she’d find out that helicopter rides made her sick. And yes, on occasion, people travelling in foreign countries where they don’t speak the language, get scammed.

The key thing is the position we find ourselves in. My grandmother would never again find herself so close to Everest, and she had spent quite a bit of money to be in that position. I will never again find myself so close to having my website show up at the top of the search results, and I’ve spent quite a bit of money to get this close. But of course I don’t know what will happen on the final leg of that journey. The people who are currently in first position might be spending just as much money as I am, and they’re doing it from a stronger starting point. Also even if I get into first position how many leads does that actually amount to? And how suitable are those leads? In both examples we have elements of uncertainty, positioning, and resources already expended.

As I grappled with this issue, it occurred to me that what I’m calling the Everest Fallacy might be viewed as the mirror image of the Sunk Cost Fallacy—particularly in this case.

If I decide to continue paying the SEO company, am I foolishly falling prey to the sunk cost fallacy?

That is, spending more money in an ultimately-doomed quest to justify the money I already spent. Or am I avoiding the Everest Fallacy, because I’ve done 90% of the things necessary to have a lead generating website, but all of that money will have been for naught if I decide to not spend the final 10%?

Certainly having the framing of the Everest Fallacy has led me to think differently about this decision, just as it probably would have caused my grandmother to make a different decision as well. Obviously such things are easier to determine in hindsight. To illustrate that, let’s turn to a few further examples of times where I failed to properly apply it.

A few years ago the band “Oingo Boingo Former Members”2 was playing in my town. I’d always enjoyed Oingo Boingo so I went to see them. As is so often the case, the show didn’t start till quite late. As a further annoyance, that night was the beginning of Daylight Saving Time, so on top of staying up late for the concert I was losing an hour to the time change. Given these factors, when they took a long break between the first and second set I decided to head home. Did I commit the Everest Fallacy? I’d put in all the effort to acquire tickets, get there, and secure a spot next to the stage. I was already going to be tired the next day regardless. Did I just refuse to suck it up a little bit and enjoy the second half of a great concert? With the distance of time, I can’t remember how tired I even ended up being or what I accomplished that next day that I wouldn’t have otherwise. But with the distance of time I regret leaving early. Increasingly I’m unlikely to even try to attend a concert. Accordingly, should I find myself at one, I need to take full advantage of the opportunity.

Once again it’s difficult to say for sure how much this qualifies as a true fallacy and how much it falls into the normal regrets of life. Is it possible that I’ve just been discussing some variant of FOMO (fear of missing out)? Arguably much of what I’ve said falls into the category: the fear of missing out on seeing Everest, not being at the top of the search results, or missing the last half of the OBFM concert. FOMO often leads one to spend time and money they shouldn’t in search of experiences that aren’t that great. (Being in a dingy run-down club on a Saturday at midnight, is not nearly as cool as people think.)

While I think the Everest Fallacy has and will continue to be useful. I’m still not 100% sure that it represents a separate mental model with distinctive attributes that set it apart as a distinct category of mistake. So allow me to offer up another example that might hit closer to home.

This past October I was lucky enough to attend the meetup for a forum I participate in. The meetup was in DC, and one of the attendees noted that the Supreme Court was in session, and it should be possible to see them in person. This attendee indicated that it should be no problem to get in because it was an extremely obscure case. They started seating people at 9 am, so that’s when we showed up. As you might imagine, given that I’m using it as an example, we did not make it in.

Had I remembered and applied the Everest Fallacy, say the night before, I would have realized that the time and expense required for someone from Utah to see the Supreme Court is at least a couple of days and hundreds of dollars. Also I would have taken into account that the advice I was receiving about the arrival time was almost entirely speculative. Based on this it would be a shame to miss out because I neglected to spend a couple more hours to get in line early. But of course missing out is precisely what happened. Once I was in line, it quickly became apparent that we weren’t going to make it in, and I was reminded of the fallacy. So I stayed in line, though it could be argued that by doing so I had switched to partaking in the Sunk Cost Fallacy.

This ping-ponging between the Everest Fallacy and the Sunk Cost Fallacy seems to be one of the central difficulties of trying to avoid one or the other. Perhaps the clearest example is my company’s SEO spending. I have decided to give them four more months—making a full two years—before calling it off. Is this me wastefully throwing away several thousand additional dollars because I’m in the grip of the Sunk Cost Fallacy, or is this me wisely paying the “final $80” required to actually see Everest? Of course my problem is more acute than my grandmother’s. She at least had already accumulated a whole host of interesting experiences in her tour of India and Nepal. Should I cancel things now, I would have gotten essentially nothing for my money.

Obviously we would like to avoid both fallacies, but it appears that avoiding one makes us vulnerable to the other. If we’re avoiding the Sunk Cost Fallacy, we may cancel things prematurely before we realize the potential benefits. But in our attempts to avoid the Everest Fallacy we may be wasting money searching for a payout that will never arrive.

If it were possible to know precisely which situation we’re in, then things would be easy. And sometimes we are blessed with such certainty, or at least a greater degree of certainty, in which case acting incorrectly is less excusable. My grandmother was more certain she would see Everest by paying $80 than I am of reaching the top of all the searches. And, if we had shown up at 6 am to stand in line for the Supreme Court I have no doubt that we would have gotten in.

I couldn’t be certain that I would have enjoyed OBFM if I had stayed. They had already played most of my favorite songs (one of the reasons why I left) so perhaps if I had stayed I would have looked back on it as a mistake. But really out of all these examples, the decision of whether or not to continue paying for SEO is the most difficult and potentially the most costly. How does a business steer a course between the two fallacies?

Part of my reason for writing this is that I’m not sure, and I’m hoping someone will see this and tell me. Clearly there’s a method which involves calculating the expected value of the SEO if it works, multiplying that by the chance that it will work, and then comparing that value to how much I’ve spent. If the expected profit is greater than the cost you would proceed. Unfortunately all of the numbers on the left side of that equation are basically no more than poorly informed guesses. It’d be nice if there was an incisive rule of thumb, though I would not be surprised if there wasn’t.

In part this is because I’ve already described two rules of thumb, and there probably isn’t a third which just happens to perfectly strike a balance between the Sunk Cost Fallacy and the Everest Fallacy. And in fact it’s possible that the Everest Fallacy should be considered as little more than an addendum to the Sunk Cost Fallacy, or a special case of FOMO, or a menagerie of vaguely connected examples in search of a common moral. But if I was going to try to come up with an official definition for both fallacies they would go something like this:

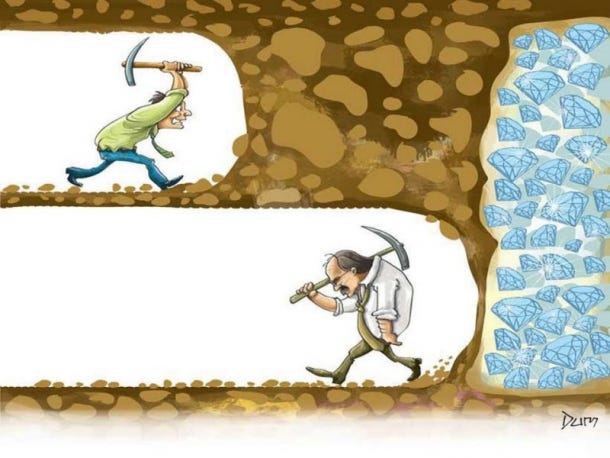

Everest Fallacy: When someone fails to consider the resources already committed towards reaching an objective which has set them such that further allocation of resources are disproportionately more beneficial. (Each additional dollar packs more punch than the previous ones.) And because of this lack of consideration they neglect to allocate those resources.

Sunk Cost Fallacy: When someone gives too much consideration towards already committed resources, reasoning that previous resources have made additional resources more impactful, when in reality if they were going to succeed they already would have, and further allocation is disproportionately less beneficial. Because of this fallacious reasoning they continue to wastefully allocate resources to an objective which is already out of reach.

I’m interested in what you think of the Everest Fallacy. Is it truly a separate bias we should be guarding against or is it some lesser construct?

In any case, I hope that I’ve provided a new way of thinking about things which might come in handy should you ever find yourself in Kathmandu.

I’m sure there have been many times when you’ve been halfway through one of my posts, and you’ve thought, “I should stop now, this is boring.” But then you’ve thought about how much time you’d already spent. But then you thought about the Sunk Cost Fallacy, and wisely stopped. Hopefully now I’ve tricked you into continuing to press on in hopes of seeing a magnificent Himalayan peak, and perhaps every so often you will, at least metaphorically (Though… perhaps I should start including pictures of such peaks at the end of my posts.)

I’m not sure how accurate the $80 figure is. When I did some searching just now, helicopter rides to see Everest cost at least $1000. However this happened at least 30 years ago, and a lot has changed since then.

Essentially everyone but Danny Elfman.

The SEO issue opens up the question of whether being in the top actually produces the leads you want? You can brute force your way into results for those search terms by buying the clicks from ad words. When you do so, do they actually produce leads or are you just paying for casual searches? Perhaps different terms are needed rather than going the last mile on the ones you're using? Do the top holders seem to be targeting those terms and are they doing with their sites what you're trying to do?

The Everest fallacy needs to ask for more information. What did your grandmother do with that $80? Did she have great conversations all night long in a local cafe? Explore parts of the city ignored by tourists obsessed with the mountain? You must weigh those experiences against maybe a half hour packed in a helicopter that may not be the safest out there. It then follows when will your next $80 get spent? By lunch time? Tomorrow? Is that $80 less important because it isn't $80 next door to Everest on the last day of your vacation?

I would've stayed at the concert, because I don't like leaving things in the middle. I'm a big FOMO person.

Regarding the SEO company, did they give you any kind of timetable on when you can expect results? Maybe they would give you one if you asked. Or have any of their reviews mentioned any time periods; "I saw my leads shoot up after two weeks!" If there's a commonality of success after such-and-such a time, and you've already passed it, that could be a clue it's not going to work for you.

On the Supreme Court trip, you said it was "apparent" once you got in line that you wouldn't get in. Did you surmise that from the size of the line, or did someone say, "Sorry, folks, we're full"? If it was the latter, and you stayed in line anyway, hoping for a miracle, then I'd say you were a victim of the Sunk Cost Fallacy. But if you took one look at the line and merely guessed, without anyone cofirming, that you wouldn't make it in before seats were full, then unless there was something else you'd been hoping to get to that day, you'd be victim of the Everest Fallacy by leaving.

Basically it seems that the better you can count the cost in any situation, the more likely you can avoid the extremes for either fallacy.