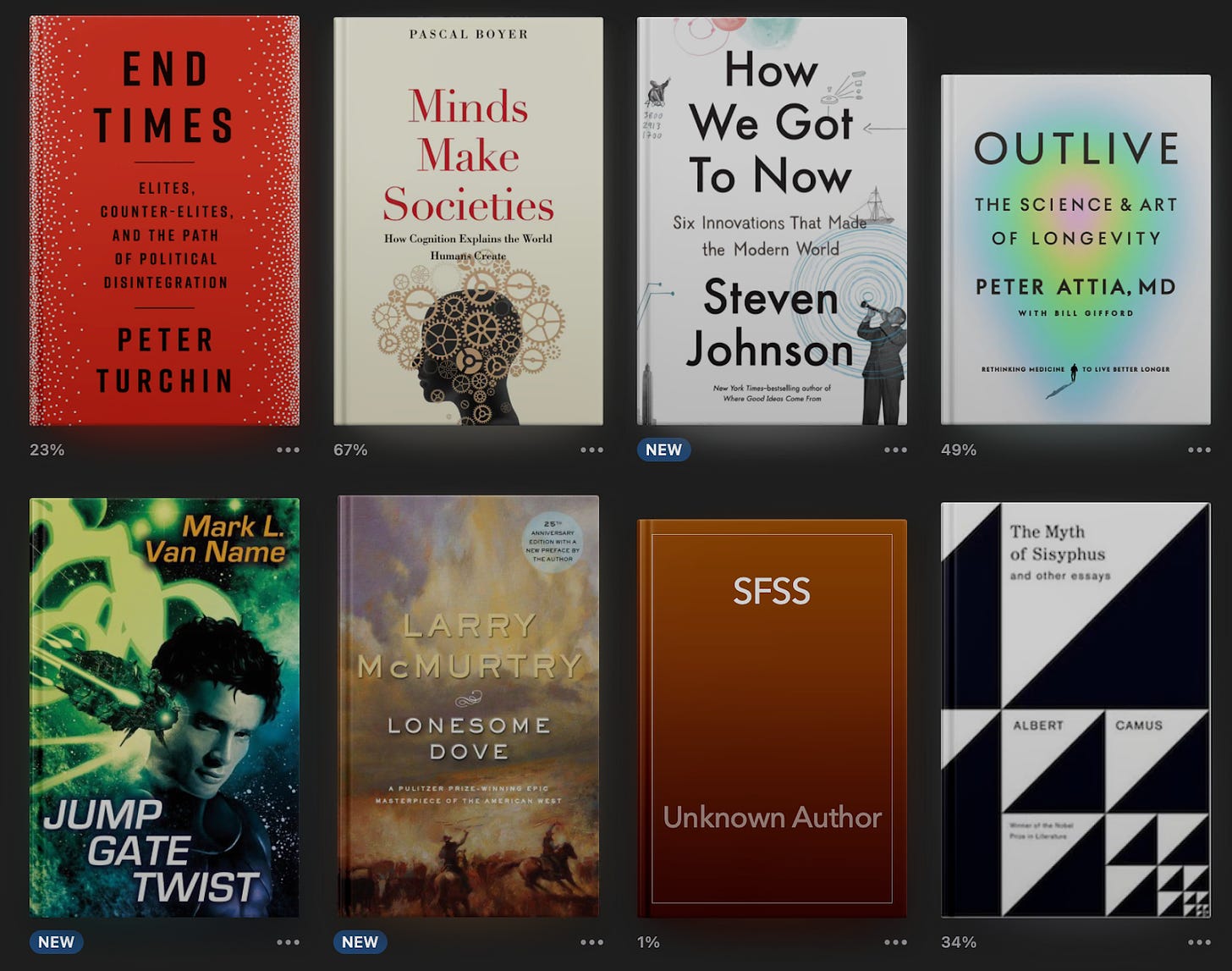

The 9 Books I Finished in July and the One I Didn’t

Some Turchin, some Attia, some Camus, some popsci, and a large dash of obscure science fiction.

End Times: Elites, Counter-Elites, and the Path of Political Disintegration by: Peter Turchin

Minds Make Societies: How Cognition Explains the World Humans Create by: Pascal Boyer

How We Got to Now: Six Innovations That Made the Modern World by: Steven Johnson

Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by: Peter Attia MD

Jump Gate Twist by: Mark L. Van Name

Lonesome Dove by: Larry McMurtry

Send Us Your Armies (Pilgrim's Path, #1) by: Vic Davis

Science Fiction Short Stories compiled by: Guy d'Andigne

Adventures of Tom Stranger, Interdimensional Insurance Agent by: Larry Correia

The Myth of Sisyphus by: Albert Camus

July is my least favorite month, and this year was no exception. It’s mostly due to the heat, so I will frequently take a vacation somewhere cooler, or at least somewhere different. This year I did the opposite and I ended up going to Moab, which is still in Utah, just a hotter part of Utah. Not only is it hotter, but I spent the vast majority of my time out of doors, camping, sans AC. We did river rafting, canyoneering, climbing, off-roading and hiking. It was a ton of fun, but it was also very hot.

It was also less than three weeks after getting back from Europe, which meant I had just barely dug out from that before I had to rush to get ahead so I could leave again. But as busy as those weeks were it was nothing compared to after the Moab Trip. A week after getting back from Moab I was scheduled to give a 45 minute presentation at a religious symposium, and despite lots of good intentions I had done nothing to prepare for that other than creating the barest of outlines. And a couple of days after the presentation I was leaving again for Gen Con. It was madness.

Gen Con was great, but I returned to another mountain of work, and this time it was too much, which is why this post is late. And things were already fraying around the edges as you may have noticed if you were following my podcast (I mixed up two recordings.) So at this point I’m going to take next week off, even from editing and reposting something old, and catch my breath.

I’m not traveling again until December, when I will be attending the Natal Conference in Austin. I’ll definitely have more to say about that as it gets closer, but for now…

I- Eschatological Review

End Times: Elites, Counter-Elites, and the Path of Political Disintegration

By: Peter Turchin

Published: 2023

368 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

That when times are good a wealth pump is created. This wealth pump inevitably immiserates the masses while serving to overproduce elites. The frustrated elites thus created pair with the increasingly angry hoi polloi to vent their frustration by upending society, sometimes violently.

What's the author's angle?

Turchin is the founder and chief advocate for cliodynamics, a (supposed?) science of history he has been developing for decades. This book is that science in a digestible form.

Who should read this book?

If you’ve ever wanted to read some Turchin this is the book to start with. I’ve read one of his previous books, Secular Cycles, and this book was much more accessible. And short, the main text was only 241 pages, though the appendices (included in the audiobook) were very accessible as well.

General Thoughts

I default to skepticism on a lot of things, but particularly specific predictions about the future, which is precisely what Turchin claims to be doing. But you have to give him some amount of credit, he was predicting back in the halcyon days of 2010 that things were going to get rocky starting in 2020. And they did. He’s definitely not the first to claim that history is cyclical in some respect, but he’s the first I’m aware of who correctly predicted the start of the next cycle.

I was curious about his original prediction, which appeared in Nature in 2010. This is not the entirety of the article (though it is quite short) but it’s the meat of his prediction:

Very long 'secular cycles' interact with shorter-term processes. In the United States, 50-year instability spikes occurred around 1870, 1920 and 1970, so another could be due around 2020. We are also entering a dip in the so-called Kondratiev wave, which traces 40-60-year economic-growth cycles. This could mean that future recessions will be severe. In addition, the next decade will see a rapid growth in the number of people in their twenties, like the youth bulge that accompanied the turbulence of the 1960s and 1970s. All these cycles look set to peak in the years around 2020.

Of course, with all such predictions there’s always going to be a fair amount of wiggle room with how it’s interpreted, and you can see where Turchin left himself a lot of wiggle room. He already admits that the 1970 peak started in the 60’s, and most people would say instability spiked in the early 1860’s with the civil war, and in the 1930s with the great depression, not the 1870s and 1920s. Still, despite the squishiness of things, one gets the sense that he might be onto something and we should at least keep this framework in mind as we attempt to navigate the coming years.

While much of the attention has been focused on his idea of “elite overproduction”, it’s when you combine it with the immiseration of the masses you end up in a familiar and well trod debate over inequality. I’ve seen many people arguing that inequality doesn’t matter. As an example Turchin relates the following conversation:

About a year or two after Donald Trump astounded the world by getting himself elected, when our political elites were still trying to process this shocking turn of events, I had an interesting conversation with one of them. Kathryn, a one-percenter herself, lives in Washington, DC, and has extensive connections among both wealthy philanthropists and established as well as aspiring politicians. She often acts as an intermediary between the two groups. She had heard somewhere that years ago I had published a forecast predicting the coming instability in the US, and she wanted to know what this forecast was based on. More specifically, she was looking for insights into why so many people voted for Trump in 2016.

I started to give her my usual spiel about the drivers of social and political instability, but I didn’t get beyond the first one, popular immiseration. “What immiseration?” countered Kathryn. “Life has never been better than today!” She then advised me to read Enlightenment Now, a then just published book by Steven Pinker. She also suggested that I take a look at the graphs on Max Roser’s website, Our World in Data. Channeling both, she urged me to rethink my take: “Just follow the data. Life, health, prosperity, safety, peace, knowledge, and happiness are on the rise.” Global poverty is declining; child mortality is declining; violence is declining. Everybody, even in the poorest African country, has a smartphone, which contains a level of technology that is miraculous compared to what previous generations had.

This is a very frequent retort, that things have never been better than now. Therefore to the extent that there is inequality it shouldn’t matter, since even the very poor are doing great on an historical basis. As mentioned in the quote Pinker is one of the chief advocates for this idea. (See my review of Enlightenment Now here.) The statistics are mixed on the question. Turchin mentions stagnating wages. But what seems more clear is that people don’t feel like things are going great, and this is what neither Pinker nor Kathryn fully acknowledge: people’s perception. Increasingly people don’t feel like they’re doing great.

As one major piece of evidence Turchin points to the massive increase in deaths of despair, the most extreme manifestation of not doing great. These deaths are a huge problem and one we’re not adequately addressing. Less dramatic, but more broad in its effect is the idea of the “precariat”. This was a term coined by Guy Standing, a British labor economist, who described the idea thusly:

It consists of people who go to college, promised by their parents, teachers and politicians that this will grant them a career. They soon realize they were sold a lottery ticket and come out without a future and with plenty of debt. This faction is dangerous in a more positive way. They are unlikely to support populists. But they also reject old conservative or social democratic political parties. Intuitively, they are looking for a new politics of paradise, which they do not see in the old political spectrum or in such bodies as trade unions.

This describes exactly the kind of surplus elite that Turchin worries about. And it’s unclear what this looks like in the statistics. They often have jobs, and a decent income, but they imagine they’d have their dream jobs and a great income. The question is how revolutionary does this make them? Certainly one gets the impression that there’s quite a bit of unrest with these people and Turchin points out that they have been a huge factor in all societal upheavals “from the Revolutions of 1848 to the Arab Spring of 2011”. Pair that with an equally dissatisfied lower class and you have a very flammable combination, one that appears to just be getting started.

Eschatological Implications

Where does all of this take us? Turchin likes to use the analogy of a game of musical chairs. Elite overproduction means that there are more and more players being created. The question most economists would ask is what's happening to the number of chairs? Many people argue that opportunities are increasing, but clearly that’s not the case everywhere. One well known example is the number of tenured professorships. This number does not seem to be increasing but the number of people getting graduate degrees has gone way up. This glut in supply has allowed universities to hire these people cheaply as adjunct professors. So the picture seems a little bit mixed.

What if some people decide to not play the game? The pandemic actually brought about a shortage of workers, leading to staffing problems in a lot of industries. Though it appears that this was mostly low wage industries, like restaurants. It didn’t solve the aforementioned problems in academia.

In addition to people choosing not to play the game (perhaps because it sucks) what if we just have fewer people overall? I’m speaking here of the much discussed declining fertility rates in the developed world. If we’re producing less people but the number of chairs stays the same then Turchin’s problem is solved. And certainly in all of the previous revolutions he’s looked at through history, declining population wasn’t a factor, since declining TFR is a very modern phenomenon.

I wonder how the surveillance state plays into this. In the past we didn’t track the number of chairs, or the people who didn’t get into chairs, or the conversations between the people who didn’t get into the chairs. These days we do. Does that make things less vulnerable to revolutions and upheavals? Or does it just delay things and make them more explosive when they eventually do happen?

On top of whatever game of musical chairs we’re playing with each other, it seems like another game of musical chairs is going on at the level of nations. There’s one chair marked hegemon, and the US has been in it for a long time, and will likely remain there for yet more time, but things are heating up. And if Turchin is correct there will be another round of unrest around 2070. But in another 50 years who knows what will happen and what the world will be like.

I’ve reached the end of my time and space and I only went through about a third of my notes. Perhaps I’ll have to revisit things at some point, but for now…

II- Non-Fiction Reviews

Minds Make Societies: How Cognition Explains the World Humans Create

by: Pascal Boyer

Published: 2018

376 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Evolutionary psychology, and the many ways in which societies and behaviors are the results of ancient incentives.

What's the author's angle?

Boyer is an anthropologist and a professor. Publish or perish doesn’t just apply to academic papers, if you really want to prosper it’s also a pretty paramount to produce popular publications.

Who should read this book?

If you want an entry point into evopsych (as it’s often called) this book is a good place to start, but for me I’d already encountered these ideas in deeper form elsewhere. Also, particularly if you spend much time in the rationalist space they’re already pretty much “in the water”.

General Thoughts

This was July’s book for the SSC/ACX book club, and everyone seemed to enjoy it. Probably because it was comfortable and didn’t challenge their biases very much. But don’t tell them I said that. (What? They sometimes read these reviews? Well crap…)

The book did provide me with one insight that I’d like to highlight:

HUMANS STAND APART FROM OTHER species in the amount and diversity of information they acquire by paying attention to other humans’ behavior, to what others do, and, crucially, to what they say. It is difficult for us to realize how much information is socially transmitted, because the amount is staggering and the process is largely transparent. There is an ocean, a mountain, a continent—such metaphors are all apt and all misleading—at any rate, an extraordinarily large amount of information that is being transferred between people, at any point, however small the community. Information is our environment, our niche, and as we are complex animals we constantly transform that niche, sometimes in ways that make it possible to acquire even more information from our surroundings.

Talking about the amount of information is important, but more important for this process to work is the amount of information you have about any given person. If we look at our early tribal roots where we were in communities of 150 people (or thereabouts) we had an enormous amount of information on each of those individuals, because we saw them every day, and knew them for years on end.

On the other end of that spectrum — the ratio of information per individual — is Twitter/X where we get tiny bits of information about tens of thousands of people. And it’s reduced to the narrowest possible bandwidth. We don’t get to hear their tone, or examine their facial expressions. We have no opportunity to observe them in a wide variety of contexts or see them interact with other people we also know well.

We’ve taken what was previously a mountain of information, and because we like the way mountains look rather than actually climbing them we take thousands of pictures of them, and spend our days watching montages of mountain scenery. Unaware of where the mountain is located or whether it’s real or generated by AI. We just like the fact that it stirs our “mountains are pretty!” sensors.

How We Got to Now: Six Innovations That Made the Modern World

by: Steven Johnson

Published: 2015

320 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The coincidental inventions and insights that created the world we now live in.

What's the author's angle?

Johnson is a popular science writer, so he has a stake in popularizing the science not necessarily nailing the implications.

Who should read this book?

If you like reading about interesting coincidences and thinking about second order effects you should enjoy this book. However I don’t think it goes particularly deep.

General Thoughts

Johnson opens his book by introducing the idea of the “hummingbird effect”. The specific term arises from the observation that the reproductive strategies of flowers led eventually and indirectly to the design of hummingbird wings. He gives several examples of this happening in the book with respect to technology. Two that stuck out to me

The invention of the printing press led to more books, which led to more people wanting to read, which led to people needing glasses, which led to better lens manufacturing, which led to telescopes and microscopes.

The invention of air-conditioning led to a lot of people moving to hotter climes which led to a rebalancing of population which led to a change in US presidential election strategy, for example Florida being a pivotal state.

It was fine as far as it went, but I think I prefer deeper analysis on a more narrow topic than this sort of wide and shallow examination. Also it’s hard to know what one should do with this information. Are these sorts of bizarre second order effects good, bad, or neutral? Should we be looking forward to unexpected innovation out of this process, unforeseen doom, or just the occasional interesting book by a popular science writer trying to make a buck?

Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity

by: Peter Attia MD

Published: 2023

496 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

An examination of the various interventions which might increase healthspan. (The span that someone is healthy, as opposed to life span which is just the span that you’re alive for, but which might include some years where you wish you were dead.)

What's the author's angle?

Attia has a very popular podcast, and while I think he would have continued to do just fine without a book to market around, I’m sure that marketing opportunities had to play some role in his decision to write it three years ago. The intervening difficulties of actually getting it across the finish line seemed to have made it more personal.

Who should read this book?

If you’re interested in the topic of health (and you probably should be) then this is a great collection of advice and recommendations from someone who seems to know his stuff.

General Thoughts

Last month I read Metabolical by Robert Lustig and I mentioned that this month I would read Outlive, and compare the two. Having done so I can confidently state I preferred Outlive. The focus was broader, though Attia agrees with Lustig on the central importance of metabolic issues, but Attia focuses on all four “horsemen” as he calls them:

Heart disease

Cancer

Neurodegenerative disease

Type 2 diabetes and related metabolic dysfunction

Outlive was also better in that it contained more actionable recommendations, though they were somewhat scattered. An appendix where he distilled down everything he had recommended in the course of the book would have been nice — perhaps a list of bullet points. (It’s possible that such an appendix is in the book, but not included in the audio. I did buy a hardcopy, but I haven’t had the chance to review it yet.)

Also Attia’s recommendations feel, in general, to be easier to follow and more realistic. Though like Lustig, when it comes to the specific area he cares about, his suggestions end up being pretty extreme. For Lustig it’s eating any kind of processed food, for Attia it’s the amount and kind of exercise. Near as I can tell Attia recommends doing about 15 hours of exercise a week of one form or another. My estimate might be high or low, as I said he doesn’t provide a distilled set of recommendations, but when he talks about his personal routine it’s clear he’s doing a lot, and a lot of different kinds. (For example he spends two hours a week just working on his stability.) But even so, exercising seems easier for me to do than avoiding all processed food, and at least Attia recommends some specific exercises while Lustig barely mentions a single food by name. I mean how am I supposed to know if ding-dongs are good or bad?

III- Fiction Reviews

Jump Gate Twist

By: Mark L. Van Name

Published: 2010

736 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The adventures of Jon and his intelligent spaceship Lobo. Military science fiction set in a universe where nanotechnology does not play well with humans, except in one case, Jon.

Who should read this book?

If you’re desperate for more military science fiction then this book will probably scratch that itch, personally I couldn’t finish it.

General Thoughts

Jon Moore is the only person in the known galaxy with beneficial nanobots inside of him. He can use them offensively, and they come in really handy on defense as well. But this fact is a secret. Jon is the lone survivor of an experiment that everyone else believes was a cataclysmic failure. As you can imagine he would like to keep this success a secret, fearing that if word got out he’d be hunted by everyone.

In addition to the offensive and defensive capabilities I already mentioned. Jon’s nanobots allow him to easily communicate with machines. They have apparently solved the AI alignment problem in this world. Without the ability or desire to plot to take over the world, AIs are forced to spend their days chatting with other AIs. This mostly consists of petty gossip.

You probably want to know why I choose to not finish the book. I’ll try to summarize:

I had hoped for a lot of interesting interactions and humor out of Jon’s ability to talk to machines. And the idea started strong, but it seemed to fade into the background pretty fast.

Like many of the books I’ve read recently Jon has a sidekick. Lobo, a small, but super deadly military ship. Lobo mostly takes over talking to machines once he enters the scene and then Jon just talks to Lobo. This would be fine if Lobo was more interesting, but let’s just say he’s no Skippy (Expeditionary Force) or Princess Donut (Dungeon Crawler Carl).

It’s not all the fault of Lobo, Jon isn’t a very interesting character either. He’s not particularly funny. He’s kind of flat, and to the extent he does have texture it involves him introspecting on how psychologically wounded he is from all the violence — before going on to commit even more violence.

The thing that actually made me stop was about 40% of the way in there was a twist. A twist I partially saw coming, and I just wasn’t interested in seeing how that twist played out. It made things more complicated and in a direction I wasn’t that interested in.

Finally, I have a goal to skip more books, since there’s a lot of them out there, and I’d hate for a mediocre book to keep me from reading (or re-reading) one that was truly great. Speaking of which:

Lonesome Dove

by: Larry McMurtry

Published: 1985

843 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Two renowned former Texas rangers decide to set off on a cattle drive which begins on the Rio Grande and ends in Montana. They encounter numerous adventures and dangers along the way.

Who should read this book?

Probably anyone who reads fiction, possibly anyone who reads period. And if you’re not much of a reader you should watch the mini-series. It’s all great.

General Thoughts

As I’ve mentioned from time to time in this space, I’m increasingly convinced that one of the best ways to relax is re-reading some classic work of fiction you enjoyed in the past, and you could hardly find a book more enjoyable than Lonesome Dove.

This time around I listened to it, and I thought the narration was excellent. Gus McCrae pops off the page, but he pops even more from the narration. I would contend that Gus belongs in the pantheon of great characters, with people like Sherlock Holmes, Hamlet, or Jane Eyre.

Speaking of great literature, I will say that some of the coincidences in the book remind me of reading Dickens, almost too improbable to be believable. But given that the population of Dickensian London was around 2.5 million and the population of 1870’s Texas was only 800,000 perhaps McMurtry’s coincidences are more forgivable.

I will say that this time around I found Elmira and July even more annoying, so annoying that it actually decreased my enjoyment a tiny bit, but just a tiny bit. Everything else is so good that such minor issues are easily overlooked. But this time around I got the feeling that they are unrealistically dumb. But perhaps that’s precisely what McMurtry was going for since it could be argued that Gus is unrealistically competent. But I far prefer reading about the latter than the former.

Send Us Your Armies (Pilgrim's Path #1)

By: Vic Davis

Published: 2020

323 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

It used to be very common that fantasy and science fiction books would feature normal humans who are somehow transported to a strange world as their protagonists. (Think John Carter of Mars, and the Pevensies in Narnia.) This is a throwback to that sort of book, though a very unusual one. Pilgrim, the human in question, is transported to a strange world of energy and thought. So it’s only his soul that’s transferred, he looks like an ovoid, who can manifest tendrils, create armored plating and turn himself into an actual one dimensional line.

Who should read this book?

This is an unusual book, it kind of has an old school feel both for the reasons mentioned above but also because it’s bildungsroman, albeit a very strange one. If that sounds appealing then you might like this book, but it’s self-published and that shows. There’s lots of initial cleverness, but it doesn’t go very deep. Though I suppose eventually it might, there are two more books.

General Thoughts

The Large Hadron Collider starts giving weird results, so humanity builds an even bigger supercollider, and eventually they realize the anomalous results represents a code which says three things:

YOU ARE IN DANGER

SEND US YOUR ARMIES

THE KEY TO THE GATE

The final bit was followed by the design of a gate, and also warnings that if they didn’t build the gate various calamities would befall them. As you might imagine, if someone can communicate with you by changing the laws of physics as revealed by a supercollider, then at a minimum they’re very powerful. And I suppose also trustworthy? Of course books like this are going to end up seeming hopelessly out of date, because the key difficulty is not deciding whether to trust the message being generated by the colliders. It’s whether to trust the scientists running the colliders, who have interpreted this data and are now communicating it to the masses.

But I digress. What I’ve described is just the prologue. From there you jump into a pretty weird world, and for a bit I wasn’t sure I was going to continue reading, but by the time Pilgrim is introduced in chapter 7 it’s settled down and it’s actually pretty enjoyable if a little bit amateurish. I would say there’s a 70% chance I’ll read book two in the series.

You may be wondering how on earth I came across this book. Well it was recommended on a blog I used to read many years ago, and after abandoning Jump Gate Twist (recommended to me by yet another guy at a networking event) I decided to try and get through the stuff that had been on my kindle forever, and that’s what this was.

Science Fiction Short Stories

Compiled By: Guy d'Andigne

Published: Other than a few outliers most of the stories were published between 1952-62

200 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

A fan-curated collection of old science fiction.

Who should read this book?

There are better collections of short science fiction. This one was okay. I wouldn’t start with it, but if you’re ravenous for short SF content, then it’s got some interesting stuff.

General Thoughts

This was another one that ended up on my kindle and I don’t remember how, and I was catching up. It’s probably a lesson about being more discriminating… But as I said the stories were decent. I think the stand out for me was “The Die-Hard” by Alfred Bester. It was basically the story of an old man who gives the middle finger to the future.

Adventures of Tom Stranger, Interdimensional Insurance Agent

By: Larry Correia Narrated by: Adam Baldwin

Published: 2016

Audio only- Two hours

Briefly, what is this book about?

The high octane life of an interdimensional insurance agent. Also it’s very self-referential.

Who should read this book?

It’s a stretch to call it a book, but if you’re a fan of either Correia, or Baldwin, or if you want some decidedly un-woke fiction, this is for you.

General Thoughts

Adam Baldwin narrates the piece, and in the book he’s also the president of an alternate Earth where Firefly ran for five seasons and brought about a cowboy-libertarian revolution. Correia is also a character in the book. Overall it was a quick, fun listen.

IV- Religious Reviews

The Myth of Sisyphus

By: Albert Camus

Published: 1942

134 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

It was pretty dense so I think I’ll just steal this from Wikipedia:

The absurd lies in the juxtaposition between the fundamental human need to attribute meaning to life and the "unreasonable silence" of the universe in response. Camus claims that the realization of the absurd does not justify suicide, and instead requires "revolt."

Who should read this book?

As I said it’s pretty dense, but if you like dense continental philosophy that makes you think then this fits the bill

General Thoughts

There’s always going to be quite a bit of overlap between philosophy and religion, but this book seemed to almost be making the case that, while Camus didn’t believe in God, if one could it would be better. I assume that I received this impression in part from my many biases, but here are some quotes, which in addition to being suggestive, are also just great quotes. (The book is full of great quotes.)

The meaning of life is the most urgent of questions.

If man realized that the universe like him can love and suffer he would be reconciled.

I want everything explained to me or nothing.

He wants to find out if it is possible to live without appeal.

Mystics, to begin with, find freedom in giving themselves. By losing themselves in their god, by accepting his rules, they become secretly free. In spontaneously accepted slavery they recover a deeper independence.

If it were sufficient to love, things would be too easy.

There always comes a time when one must choose between contemplation and action. This is called becoming a man. Such wrenches are dreadful. But for a proud heart there can be no compromise. There is God or time, that cross or this sword. This world has a higher meaning that transcends its worries, or nothing is true but those worries.

Here’s another great quote: “You get what you pay for.” If you would like to get more (which certainly seems doable) then consider donating.

You say you default to skepticism regarding predictions of the future, but doesn’t belief in religion (and eschatology in particular) involve setting aside skepticism about a certain set of predictions? Or are you just saying that you are skeptical of predictions other than the ones you have chosen to believe?