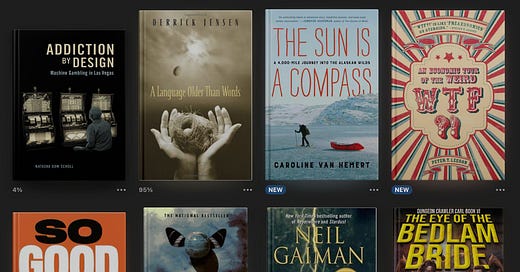

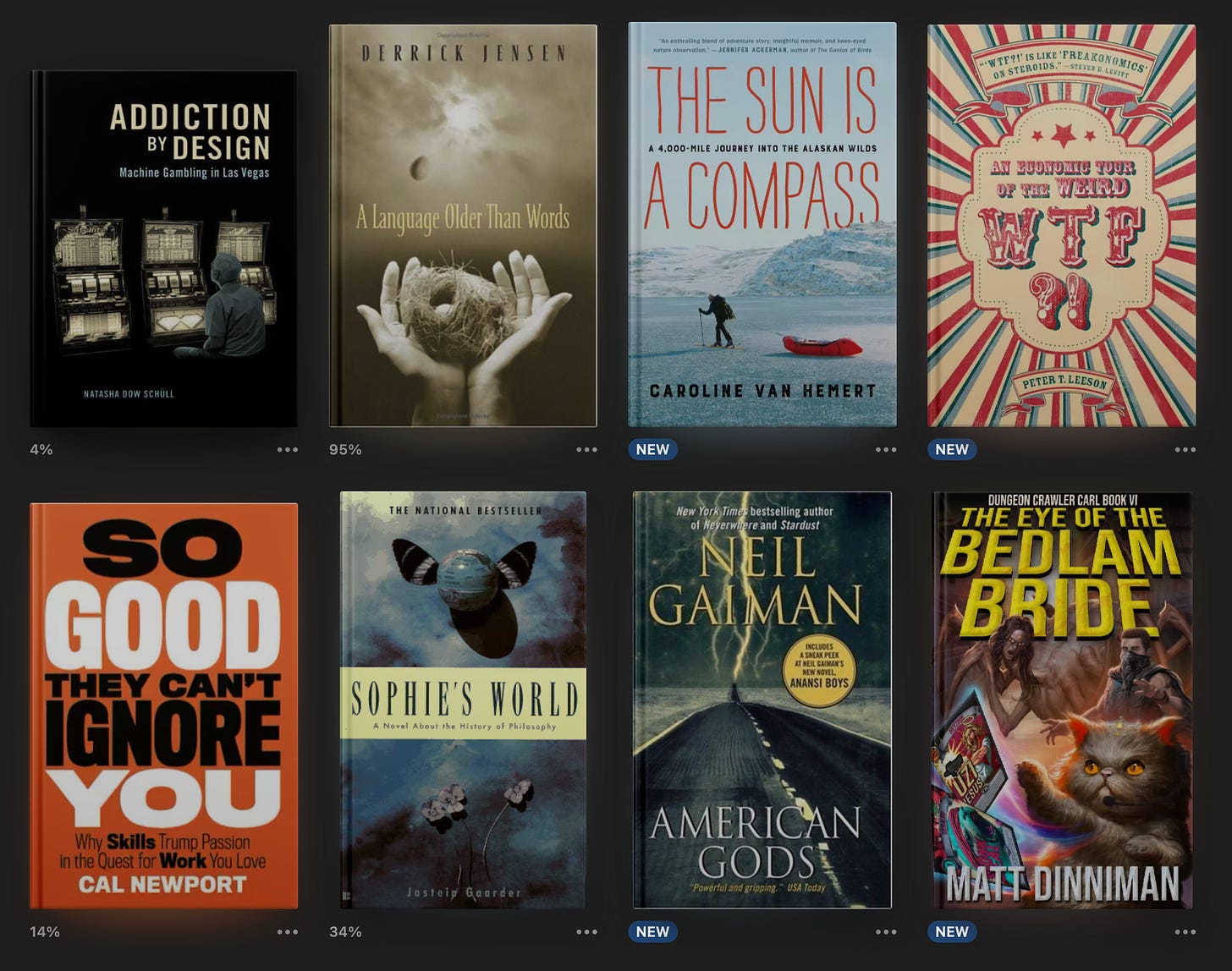

The 12 Books I Finished in September

Addiction by Design, A Language Older Than Words, WTF?!, Blowback, The Sun Is a Compass, So Good They Can't Ignore You, Sophie's World, Sandman 4, American Gods, Letters to a Young Mormon, +2 more!

Addiction by Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas by: Natasha Dow Schüll

The Evolutionary Limits of Liberalism: Democratic Problems, Market Solutions and the Ethics of Preference Satisfaction by: Filipe Nobre Faria

A Language Older Than Words by: Derrick Jensen

WTF?!: An Economic Tour of the Weird by: Peter T. Leeson

Blowback, Second Edition: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire by: Chalmers Johnson

The Sun Is a Compass: A 4,000-Mile Journey into the Alaskan Wilds by: Caroline Van Hemert

So Good They Can't Ignore You: Why Skills Trump Passion in the Quest for Work You Love by: Cal Newport

Sophie's World: A Novel About the History of Philosophy by: Jostein Gaarder

The Sandman: Book Four (The Sandman #4) by: Neil Gaiman

American Gods by: Neil Gaiman

The Eye of the Bedlam Bride (Dungeon Crawler Carl #6) by: Matt Dinniman

Letters to a Young Mormon by: Adam S. Miller

September was largely uneventful, for me at least. The same can not be said for Brandon Hendrickson, good friend of the blog. He won the Astral Codex Ten book review contest with his review of The Educated Mind, by Kieran Egan. I mention this not only to bask in the reflected glory but because I ended up recording the audio version of his review. It’s a long review so the audio comes in at over three hours (another source of my busy summer) but it is worth listening to. As they say thousands of Astral Codex Ten readers can’t all be wrong…

Also I apologize that this post is on the late side. As I may have mentioned I pushed myself too hard over the summer and ended up burned out, and my writing mojo is taking longer to recover than I expected. Also maybe I shouldn’t read so many damn books…

I- Eschatological Review

Addiction by Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas

Published: 2012

456 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The way computer technology enabled the creation of ever more sophisticated slot machines. These machines are far more addictive than the old machines, but that also made them far more profitable.

What's the author's angle?

The author is an academic, and this is her multi-year research product. Overall she seems pretty objective, though it wasn’t easy, the resemblance between the manufacturers of slot machines and tobacco companies is hard to miss.

Who should read this book?

The book is on the academic side, so it’s long and dry. If you want lots of sad stories about people addicted to video poker, then this is a good book for that. Otherwise I would probably skip it. The problems she describes are pretty obvious, you’re probably already convinced of them. That said, they’re problems we don’t have a solution for that seem to be getting worse.

General Thoughts

Until the mid-1980s, green-felt table games such as blackjack and craps dominated casino floors while slot machines huddled on the sidelines, serving to occupy the female companions of “real” gamblers. Often placed along hallways or near elevators and reservation desks, rarely with stools or chairs in front of them, the devices occupied transitional spaces rather than gambling destinations. By the late 1990s, however, they had moved into key positions on the casino floor and were generating twice as much revenue as all “live games” put together. In the aisles and meeting rooms of [the industry’s annual expo], it became common to hear gambling machines referred to as the “cash cows,” the “golden geese,” and the “workhorses” of the industry. Frank J. Fahrenkopf Jr., president of the American Gaming Association, the commercial interest lobby that sponsors the annual expo, estimated in 2003 that over 85 percent of industry profits came from machines.

This book tells the story of how slot machines went from an afterthought to the dominant form of gambling revenue for the casinos, and all by designing them to take advantage of built in evolutionary quirks. Schüll doesn’t use the term supernormal stimuli, but their presence is all through this book. For example:

Multiline video slots’ subtle yet radical innovation is precisely their capacity to make losses appear to gamblers as wins, such that players experience the reinforcement of winning even as they steadily lose. “Positive reinforcement hides loss,”

The most common way this is done is by programming the machines to display lots of near misses. Situations where it looks like the person paying almost hit the jackpot but they were half an inch off. All of this is an illusion. Video machines don’t have actual reels or actual cards, they can display whatever they want. They mess with our inbuilt model of how the world should work. The real chance of getting a particular payout might be one in a thousand, but all the near misses convince the player it must be much higher. And of course it goes far deeper than that. I’m sure near misses tie into some evolutionary hook like food gathering by our distant ancestors, where near misses actually contained valuable information.

In addition to making it seem like you’re close to winning, the machines now operate on the principle of giving people frequent small wins. Not that you’re actually making money, but it’s only after the fact that this becomes apparent. In the moment it seems like you’re doing pretty well. Everytime you turn around you’re winning something, making this feel like a beneficial activity. But in reality continued play will eventually drive you to extinction (an actual phrase gambling executives use). However, knowing this requires dispassionate and longterm accounting, which is difficult to pull off while getting all this positive feedback. In the process of making all of these changes slots became the “cash cows” of the gambling industry. They also became incredibly addictive:

In 2002 the first in a line of studies found that individuals who regularly played video gambling devices became addicted three to four times more rapidly than other gamblers (in one year, versus three and a half years), even if they had regularly engaged in other forms of gambling in the past without problems.

So the casinos have figured out how to use technology to hack a segment of the population such that they act completely irrationally, and then they prey on these “hacked” people deriving upwards of 60% of their total revenue from gamblers who are addicted. This is pretty bad, the question is where’s it heading and has it spread?

Eschatological Implications

You’ll note that most of the dates mentioned so far were 20 years ago, and the book was published over ten years ago. So where are things now, and has this addictive design moved to places outside of gambling? In other words, given how bad it was back then, one would expect it to be truly apocalyptic now, and if it’s that effective to get people addicted to slots, why aren’t we seeing the same tactics applied to video games and social media? It kind of feels like we are, but it’s mostly time that people are wasting, not money.

Gen Z spends half its waking hours on screens (7.2 hours a day) according to the LA Times. Other places say it’s even higher than that. I’m seeing figures of 10.6 hours a day on online content. That sounds pretty crazy to me. And sure there is some alarm, but it never feels as big or as urgent as it should be.

So where does it go from here? Does it get better because we get wiser? Does it reach some sort of manageable plateau, not getting better or worse? Or does it expand indefinitely until we reach some kind of cataclysm?

Given the recent increase and liberalization of sports betting, it doesn’t feel like we’re getting wiser. My best guess would be that this is just an additional catastrophe waiting to play out? And what about areas outside of gambling?

I recently saw a collection of weird roommate stories. One of them seemed depressingly appropriate to this topic:

My first ever roommate freshman year of college was one of the most impressive people I had ever met. He had a great job that covered his cost of living and tuition (this is 2006), had his own place, was getting great grades in a tough program, and was with an amazing woman. I was super stoked when he offered to let me rent the 2nd room. Over the next year I watched all that fall apart due to a sudden and overwhelming WoW [World of Warcraft] addiction. I can still remember the time when I was trying to get him to log off because he was about to miss this long-standing, fancy night out with his [girlfriend]. He looked at me with genuine remorse and said “I can’t.”

Compare that to this story of someone playing the slots.

After sitting at a machine for fourteen hours, so tired I can barely keep my eyes open, no money in my pocket, no gas in my car, and no groceries at home, I still can’t leave because I have four hundred credits in the machine. So I sit there for another hour until it’s all gone, praying for me to lose: Please God take this money so I can get up and go home. You might ask, Why didn’t you hit the cash out button? That never occurred to me—that was not an option.

As I said, is the only difference that people are wasting time but not money? Will that forever be the case?

I was talking to a friend recently, and I casually asked him if he had any plans for the weekend. He mentioned that he had his stepson, but they didn’t really “have him” because he wanted to spend all of his time on Roblox. And not only all of his time, but all of his meager allowance as well. There’s significant debate over whether one should actually apply the label of addict to someone who’s unusually attached to a video game, but that term certainly seems applicable to the story above, and it also seemed to apply to my friend’s step son.

My friend is obviously concerned. He’s thinking of banning the game for a month, which he thinks would probably work. But even if it did, what are his son’s long term prospects? He’s already got pretty severe ADHD. He doesn’t do well in school. Where does he end up if the minute you turn your back he’s going to be playing Roblox 24/7? And perhaps more importantly, if hacking customers becomes more common, where does society end up?

II- Non-Fiction Reviews

The Evolutionary Limits of Liberalism: Democratic Problems, Market Solutions and the Ethics of Preference Satisfaction

Published: 2015

320 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The inability of market based solutions to solve the weaknesses of democracy, in particular evolutionary fitness at the group selection level of evolution.

What's the author's angle?

As I recall this is another PhD dissertation turned into a book. (Is it good or bad that I read so many of these?) He seems to have a certain animus towards public choice theory but based on his reading of the literature and the data, he came by it honestly.

Who should read this book?

The book is on the dry side, and he takes a while to get to his point because he has to cover all of the relevant academic territory first. When he gets to his point it’s great and interesting, but I’m not sure how many people will think it was worth the effort it takes to get there. But if you’re interested in the subject and this review is not enough, then by all means you should read the book.

General Thoughts

There have been several books recently which have taken a hard look at liberalism and found it wanting. Perhaps the most notable is Why Liberalism Failed by Patrick J. Deneen (see my review here). There’s a lot of overlap between that book and this one. Both assert, among other things, that you can’t create a cohesive and successful society by prioritizing individualism (i.e. selfishness).

As you might guess from the title Faria puts an evolutionary spin on things. There’s good evidence that in addition to natural selection at the level of the individual and their genes, there is also group selection. As you might imagine any ideology which prioritizes individual preference satisfaction is going to be bad at prioritizing the survival of the group.

So how does one create a cohesive society that survives? Faria actually talks a lot about morality. He points out that if you’re talking about group morality it has to be something held by the elites as well as the masses. That if anything the elites have to be at the forefront of things for morality to be successful. As a description of an actual phenomenon he seems to be thinking more of a civic religion than an actual religion, though either would seem to do the trick. He never points to a specific example, but certainly if one looks at old school American patriotism, it definitely fits the bill. World War II is a great example of its vitality and its ability to triumph at the level of group selection.

Flashing forward to the present day, we still have elite-driven morality, but in the West it’s a morality of individualism, which makes it ill-suited as the basis for evolutionary strong groups. Faria points out that authoritarian regimes have an easier time imposing a morality. And in some senses this is their great strength, authoritarian regimes always have a civic religion, one that ends up being surprisingly effective given the numerous other weaknesses of authoritarianism.

In the eventual (and unfortunately current) battles between cohesive authoritarian societies and individualistic liberal societies who will eventually triumph? Faria doesn’t think it will be the authoritarians necessarily, but they certainly could triumph if Western democracies don’t get their act together. And one of the main contentions of the book is that market solutions are not a way of getting that act together.

Before we can pass final judgment on Faria’s ideas we need to remember Fukuyama’s claim, a claim that Faria doesn’t cover. Liberal markets and the countries that possess them are better at technology. So does authoritarian cohesiveness eventually beat technological sophistication? Or will tech perpetually keep liberal societies on top. That would appear to be the big question for the future.

My personal opinion would be that thus far, authoritarian societies, in particular China, have done a better job of dealing with their weaknesses in technology than liberal societies have done dealing with their weakness in societal cohesion.

A Language Older Than Words

By: Derrick Jensen

Published: 2004

418 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

One-third memoir, one-third an elegy for nature writ large, and one-third a call for a return to and a greater understanding of nature as a way of saving it.

What's the author's angle?

Jensen is a hardcore environmental activist, and he makes no claims at being dispassionate. In fact the book is unapologetically full of fervor and fury.

Who should read this book?

Jensen is one of the leaders of Deep Green Resistance (DGR). When I was at their conference I asked him which of his books I should read first, and he said this one. Should you find yourself in a similar position then I would offer the same advice.

General Thoughts

When I returned from the DGR conference numerous people asked me, “How do they propose to handle X.” More often than not I had to say, “That didn’t really come up.”

I hoped that the book would cover all of the things that I and others were curious about that didn’t come up in the conference. They sort of do. But as I said only one third of the book offers anything approaching a plan, and that plan is mostly laid out through personal anecdotes. There’s very little space devoted to what would be required to bring about the massive changes necessary to get us to the world Jensen imagines. And almost no space devoted to the consequences of those changes

To the extent that there is a plan it’s alluded to in the title. Jensen offers numerous anecdotes from his own life of being able to communicate with animals and even plants. Presumably if something like that were possible then you could imagine that it would be worthwhile to work together with the wildlife to save the planet. Since humans have mostly been responsible for screwing things up, perhaps the wisdom of the animals would be necessary to reverse that.

Certainly it’s a nice idea, and Jensen even offers up some evidence for the reality of this sort of communication. It doesn’t come till 80% of the way into the book which is a weird place to put it. Still he does have some evidence, which is more than I can say for some of the books I’ve read recently.

What is this evidence? Jensen talks about meeting with Cleve Backster, a polygraph specialist who started hooking some of his polygraph equipment to plants. He then noticed that plants would react to things he was doing. This would only be possible if plants possess some form of extrasensory perception.

Backster was a big enough deal—he started the CIA’s lie detector division—that scientists initially took him seriously and many tried to replicate his findings. His claims even made it onto Mythbusters. Unfortunately no one was able to replicate his findings. Now there is an unfalsifiable explanation for why they were unable to do this, but still as evidence goes, it’s not what you would call “ironclad”.

Those portions of the book dedicated to the plan were disappointing. The memoir portions on the other hand were quite good. Jensen is an evocative writer and he has some great stories. Some of the stories are hard to read, as much of the memoir is about his abusive father, but they were powerful.

Overall I’m glad I read the book. It was definitely outside of my wheelhouse, but that’s precisely why I’m glad. It’s always good to expand your horizons, and engage in true diversity: intellectual diversity.

WTF?!: An Economic Tour of the Weird

By: Peter T. Leeson

Published: 2017

264 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Strange historical practices that nevertheless make sense once you understand the incentives.

What's the author's angle?

This may sound harsh, but I think the author is very dedicated to displaying his own cleverness.

Who should read this book?

If you enjoyed Freakonomics (the book or the podcast) then you’ll probably enjoy this book. If you can get past the tone…

General Thoughts

This was another selection for the SSC book club I belong to, and while informationally it’s very interesting, tonally it drove me nuts. The conceit of the book is that there is a museum of weird economic stories. The chapters are presentations given by the museum's curator. These presentations are interspersed with dumb questions from a group he’s taking around the museum. In addition to pointing out how dumb the questions are, the curator insults the people asking the questions. One of the characters is an overly earnest liberal female who he constantly refers to as Janeane Garofalo. (The other people at the book club who are all younger than me, some much younger, had no idea who this was.) All of this was so annoying that it just about kept me from finishing. Which would have been too bad, his examples are really interesting, but man, the presentation!

It’s entirely possible that I’m being too hard on him. That this tone issue is a personal quirk of mine and you will not find it nearly so annoying. (The other people who read the book were all annoyed by the tone, but not as much as me.) In an effort to balance things out, here’s a few of the topics he covers. He gives interesting (if overly long—there I go again) explanations of these seven historical practices:

Medieval religious ordeals (plunging arms in boiling water) to determine guilt or innocence.

Eating poisoned chickens as a way of settling disputes.

Spousal Auctions

Gypsy taboos around what’s unclean

Trial by combat for settling land claims

Putting insects and other vermin on trial.

Medieval monastic maladictions

It is a tour of the weird. Unfortunately it could have been a much more pleasant tour.

Blowback, Second Edition: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire

By: Chalmers Johnson

Published: 2000

288 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The many selfish decisions, unwise actions, and outright crimes America has been involved in as it sought to maintain its empire. And how all of this leads to a widespread and global hatred of the US.

What's the author's angle?

One definitely gets the feeling that Johnson has an ax to grind; that he had a very clear vision of what should have happened after the Cold War ended, and was disappointed by what actually happened.

Who should read this book?

It’s somewhat dated. When it was written the US could have done whatever it wanted, and there’s plenty of room for second guessing what we actually did. These days our choices are fewer and the enemies both more obvious and more powerful.

General Thoughts

This was published before 9/11. In some respects that doesn’t matter since our foreign policy got more aggressive in its wake and we did more of the sorts of things Chalmers is complaining about. Also 9/11 is an example of exactly the kind of blowback that Chalmers is talking about.

On the other hand 9/11 basically changed everything. Back then North Korea didn’t have nukes. Taiwan was expected to easily defend itself against a Chinese invasion, and our muscular military presence seemed like a relic of a different time and completely unnecessary.

As an example of this heavy and unnecessary US military footprint. Chalmers spends a lot of time talking about Okinawa. The US Military uses 18% of the land, has 31 separate military installations, and there are 80,000 Americans on the island. In addition to all of the normal inconveniences, the Okinawans occasionally experience horrific crimes, like the 1995 rape of a 12 year-old Okinawan girl by three US serviceman.

I remember when that happened, and it was a big deal. But I don’t remember anything like that being in the news recently, or really much of any news about the inconvenience of the American presence. Apparently it is still a burden, just not one you hear about. Is this because now that China is resurgent everyone considers it to be a necessary evil? But if everyone in Southeast Asia (Chalmers area of expertise) is so worried about China, why do they consistently spend so little on their own militaries? Japan spends 1% of its GDP on it’s military and Taiwan, which clearly seems to be in the crosshairs, only spends 2.5% of its GDP, as compared to 3.5% for America. Does this not on some level indicate that we’re more worried about China than they are?

As things heat up will all of these countries end up grateful for the American military's many foreign adventures, or will all of this congeal into an global anti-American coalition despite the many crimes of Russia and China?

And because these reviews were so delayed, we know get to consider Hamas’ invasion of Israel. Is this another example of blowback against American Hegemony? Will American support of Israel make the global hatred worse? How will it affect our ability to assist Ukraine and defend Taiwan? It definitely feels like global complexity and fragility are both increasing.

The Sun Is a Compass: A 4,000-Mile Journey into the Alaskan Wilds

Published: 2019

320 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The adventures of the author and her husband as they go on an epic 4,000 mile journey that starts in northern Washington, follows the Canadian Yukon north, follows the coast of Arctic Ocean, before finally ending on the west coast of Alaska, just above the Bering Strait.

What's the author's angle?

Oftentimes books like these come with a pretty heavy message (see A Language Older Than Words above) this book is pretty light on that front. It mentions global warming only briefly, and to the extent it does have a message it’s “doing hard things in nature is amazing.” A message I can definitely get behind.

Who should read this book?

If you’ve ever felt the pull to do something epic in the wilderness you’ll enjoy this book.

General Thoughts

Most people, including myself, could never pull off a journey like this one. The book was interesting just for the sheer ambition it displayed. I also quite enjoyed its meditative aspects. There's something about being out in nature that is beneficial and deep in a way that’s hard to quantify, but also very necessary. As I mentioned in my review of the Comfort Crisis.

Beyond that I’m not sure what else to say, the journey is epic, and that by itself makes it worth reading about, particularly in an age that seems to increasingly shy away from the epic.

So Good They Can't Ignore You: Why Skills Trump Passion in the Quest for Work You Love

By: Cal Newport

Published: 2012

304 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The advice “Follow your passion!” is dangerous and misleading.

What's the author's angle?

Newport generally practices what he preaches, but that doesn’t mean that what works for him will work just as easily for you.

Who should read this book?

I think this would be a great book for people just starting college or just graduating from high school. I suppose it would also be great for people thinking about a career change but the advice there might be to stick with the career you already have and get better at it.

General Thoughts

I thought this book paired well with The World Beyond Your Head which I reviewed last month. People have a tendency to fetishize their preferences, but all of this assumes a weird almost supernatural epistemology. That there is some force deep inside you that knows exactly what will make you happy, and that this is not at all based on a desire for status or sloth.

Newport doesn’t quite phrase it this way, but he points out that enjoying what you do is less about passion and more about mastery. In particular he identifies three things that make a profession worthwhile:

Autonomy: the feeling that you have control over your day, and that your actions are important

Competence: the feeling that you are good at what you do

Relatedness: the feeling of connection to other people

Accordingly before you leave a job a better first step would be to see if you can increase any of those three qualities.

III- Fiction Reviews

Sophie's World: A Novel About the History of Philosophy

By: Jostein Gaarder

Published: 2007

544 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Philosophy as one would explain it to a 14 year old girl.

Who should read this book?

As an intro to philosophy this wasn’t bad. If my kids were younger or took my recommendations I might suggest that they read it.

General Thoughts

I almost put this in the non-fiction section. It does come across as something like a textbook, a very engaging text book, but a textbook nonetheless. It’s somewhat redeemed by the narrative and the characters, but you should read it for the information, not the story. And as far as that goes, I think reading this when I was much younger would have been great, as it was, I didn’t learn much I didn’t already know.

The Sandman: Book 4 (The Sandman #4)

By: Neil Gaiman

Published: The comics were originally published starting in 1989.

528 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Morpheus is being hunted by the furies for strange and seemingly opaque reasons.

Who should read this book?

If you haven’t read all the proceeding comics you’re going to be completely lost. Even if you have, you're going to be a little bit lost. But as this is a great series it’s worth not only reading, but finishing.

General Thoughts

This was a good, albeit strange ending to the series. I had long wanted to read these comic books, and I’m glad I did. I have yet to decide if I’m going to partake of any other Sandman related content. Should you have strong opinions on that let me know.

American Gods

By: Neil Gaiman

Published: 2001

465 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

All the gods exist, but without worship they’ve dwindled till they’re only slightly more powerful than an average human. The main character, Shadow, has been recruited by Odin (who goes by the name Wednesday) to help him in an upcoming battle between the old gods and the new (TV, internet, etc.)

Who should read this book?

This would be pretty high on my list of favorite novels. It is a little more adult than most of Gaiman’s books. But that caveat aside, I highly recommend it to anyone who likes speculative fiction.

General Thoughts

It’s interesting how many of the themes in American Gods were present in Sandman. I could complain that this demonstrates a lack of originality, but I’m more inclined to say that it’s more representative of a pleasing depth. To give one example, Gaiman has really done a lot to make the Norse Gods interesting.

I just read an article about the disappearance of regional American accents, and it reminded me that there was a time not that long ago when America was weirder, more fragmented, and more fantastic. I bring it up because American Gods is a great representation of that old, weird America. An America that I quite enjoyed…

The Eye of the Bedlam Bride (Dungeon Crawler Carl #6)

By: Matt Dinniman

Published: 2023

694 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The continuing adventures of Carl and his sentient cat Donut. On the current dungeon level they’re forced to play a strange game where the monsters they fight can be turned into cards and collected.

Who should read this book?

If you’ve already read the first five books and enjoyed them you should definitely read this one. It’s got 4.9 stars on Amazon and 4.8 stars on Goodreads. If I sort all the books I’ve read by user rating, and eliminate books with fewer than five ratings, and books written for Mormons (where the rating has been artificially inflated out of religious zeal). This book has the very highest rating of any book I’ve ever read.

If you haven’t started the series, then I’d wait and see what people (including me) have to say about the next book in the series. I felt like in this book the number of crude jokes definitely went up, making me less likely to unreservedly recommend the series. Also much of the quality of the series would appear to hinge on what happens in the next book.

General Thoughts

Contra Goodreads, I do not think this is the best book I’ve ever read. But it was pretty good. With a long running series like this, one is always interested in seeing what happens to the protagonists. But in broad strokes you know they’re going to eventually triumph, so there’s a limit to how much mystery there can be.

This is not the case when it comes to world building, there the author has nearly unlimited scope, and it’s one of the elements that I pay the closest attention to. Previous to this book the world building had been decent, if a little bit silly and implausible. But during this book, it definitely took a big step up. I’m very excited to see where Dinniman goes with things.

IV- Religious Reviews

Letters to a Young Mormon

By: Adam S. Miller

Published: 2018

96 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

A series of short pieces on various topics (sin, faith, prayer, science, technology, etc.) These are directed at younger church members.

Who should read this book?

I think anyone who's a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints should read this book. Miller is great at presenting profound doctrine in an accessible fashion.

General Thoughts

Someone I know is investigating the Church, taking the missionary discussions, and reading the Book of Mormon. One day he texted me to ask for some good works of Mormon apologetics. I gave him a few, and then I asked around for other recommendations. Everyone I talked to mentioned this book, and I realized that while I had read some other stuff by Miller I hadn’t read this, so I picked it up.

As you can see it’s short, but it packs a punch. I particularly liked the “letter” he did on sex. That’s a subject that is always going to be difficult to gear towards a “young” audience. And it’s not easy to present to an older audience either.

This post is late, long, and a little lazy…

What else do you want? I said I was being lazy!

I did read "Sophie's World" when I was in high school, and I thought it wasn't so interesting. In particular, I didn't get the metafictional ending at all - I understood it, but it seemed put-on and unwarranted.

I don't remember much of what I thought about the rest of the book, so I probably assimilated it into the gestalt of my history-of-philosophy knowledge without much more.