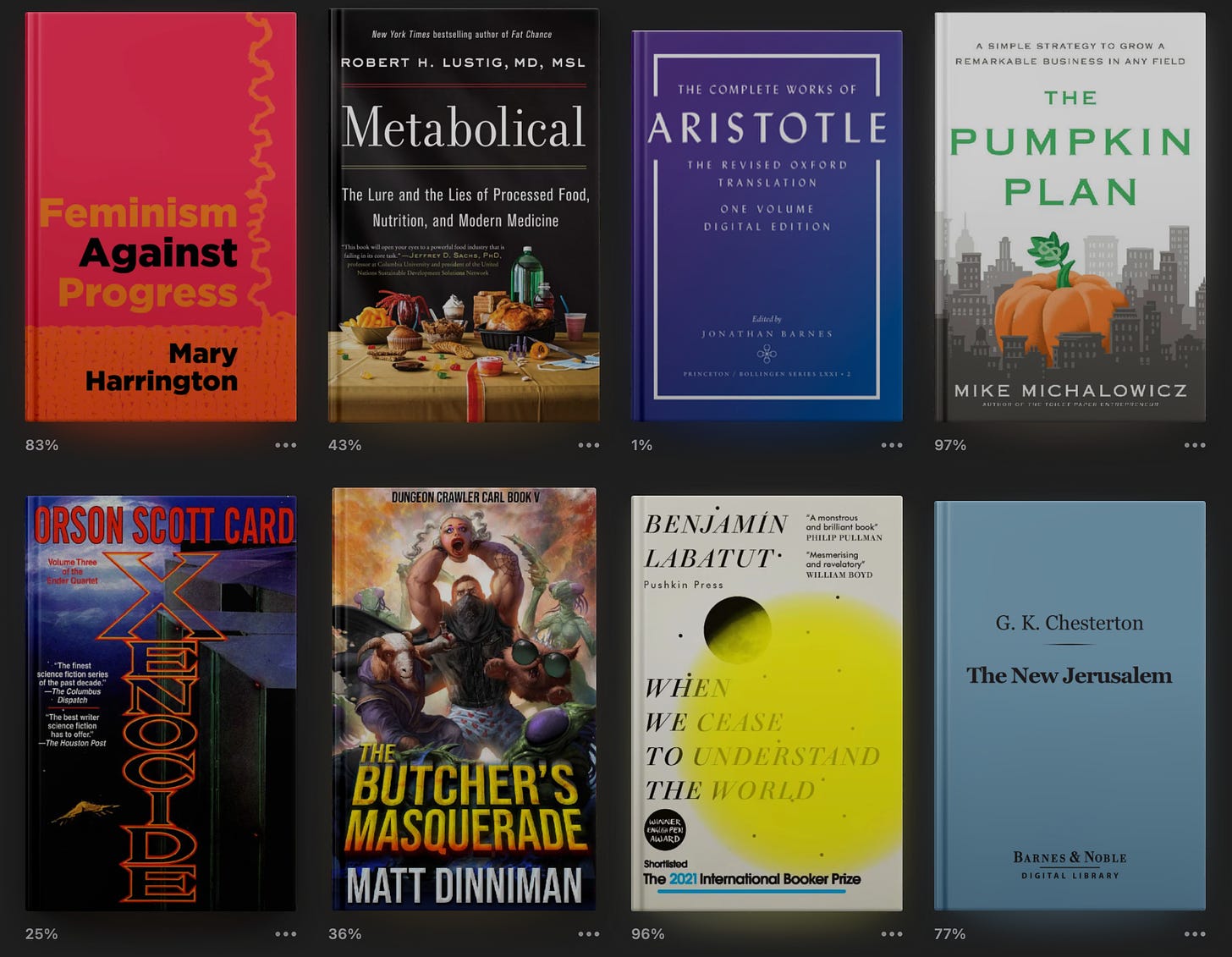

The 10 Books I Finished in June

But above all I want to go back to it, not because I know it was the right place but because I think it was the right turning. And the right turning might possibly have led me to the right place;

Feminism Against Progress by: Mary Harrington

Metabolical: The Lure and the Lies of Processed Food, Nutrition, and Modern Medicine by: Robert H. Lustig

Categories by: Aristotle

Prior Analytics by: Aristotle

The Pumpkin Plan: A Simple Strategy to Grow a Remarkable Business in Any Field by: Mike Michalowicz

The Butcher's Masquerade (Dungeon Crawler Carl #5) by: Matt Dinniman

Xenocide (The Ender Saga #3) by: Orson Scott Card

When We Cease to Understand the World by: Benjamin Labatut

The Sandman: Book Three (The Sandman #3) by: Neil Gaiman

The New Jerusalem by: G. K. Chesterton

I spent the last half of June in Europe. Three years ago my wife and I had decided to go on a Rhine River cruise for our 25th wedding anniversary. In addition we were going to spend some time in the Netherlands — where I served my LDS mission many, many years ago. If you've done the math you'll have already figured out this was 2020, and we all know what happened in 2020. We rescheduled for 2021 only to have it once again get canceled. (It was in June, I think they were back to doing cruises by August, but from what I hear the precautions were beyond onerous.) We skipped last year mostly because we decided to move and there was no way my wife wanted to try to do both. After all that this year was finally the year.

The cruise was great, though I think we over scheduled ourselves. The time in the Netherlands was less busy, but I did spend a lot of time driving around. In retrospect this was probably a mistake. The Netherlands is not a particularly car friendly country, and mostly the places I wanted to go were in the city center which was even less so. If we do it again I think I'm going to choose a home base and then sally forth from there using trains and bikes.

I managed to keep putting out posts, but it wasn't easy, so you better have appreciated it! 😉

I- Eschatological Review

Feminism Against Progress

By: Mary Harrington

Published: 2023

256 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Feminism has long been seen as inextricably linked to progress and progressive thinking. In this book Harrington lays out a version of feminism which eschews current progressive thinking and many of the tools of progress which have been closely associated with feminism — for example, the pill.

What's the author's angle?

Harrington experimented with all the things that make up the current culture of the far left. But after that experimentation ended in disaster she realized that her “queer-theory-inflected, double-liberal, anti-hierarchical idealism” had all been garbage and that what she really wanted was marriage and kids.

Who should read this book?

I’m sure that women have a different experience reading this book than men do. Since I fall in the latter category I’m not sure whether or how to recommend it to the former. But I think outside of Harrington’s specific female-focused recommendations, that the book would be enjoyed by anyone who wants a semi-theological overview of the current world. As one small example of this, everyone seems to love her term “Meat Lego Gnosticism”.

General Thoughts

As you might gather from the title, Harrington is a progress skeptic, or more specifically she’s skeptical of Progress Theology. As a definition of what this theology entails she draws on the thinking of legal scholar Adrian Vermeule:

…he calls [it] ‘sacramental liberalism’, a ‘lived and very concrete type of political-theological order’ representing ‘an imperfectly secularized offshoot of Christianity’. This quasi-theological regime, he argues, takes as its central sacrament the disruption of existing norms, in the pursuit of an ever-receding goal of greater freedom, transformation and progress towards some undefined future goal of absolute human perfection – that we somehow never attain, and whose externalities are never counted, save as further evidence of how far progress still has to go.

The key term in the list above is transformation. As with so many women in this space (TERFs if one is being pejorative) Harrington expresses alarm at the revolutionary changes being wrought by the transgender movement. She sees this movement as coexistent with transhumanism, with both emerging from a Cyborg Theocracy. But Harrington doesn’t just focus on the transformations which are happening right now, she also spends a lot of time on the transformations which have already happened.

Harrington points out that many conservatives are fixated on the transition that happened in the 60s with the sexual revolution. This leads them to long for an imagined Eden of the 50’s. But Harrington points out that the first transition happened with the industrial revolution. That’s when historical gender norms and the distribution of labor were really disrupted. As such much of what we think of as traditional gender divisions were actually a response to this. (Her discussion of Jane Austen on this point is very interesting.)

This is not to say that the 1960’s weren’t hugely transformative, but for Harrington they represent the end of one period of transformation and the beginning of a new one. The previous period was a feminism devoted to mitigating the changes wrought by industrialization and modernity. The new period was the postmodern one, when feminism moved from changing what females could do to changing what they are. The first step in this process was the pill. Which seemed so straightforward, and beneficial, but really it opened up the floodgates. It was the first step in seeing the body, particularly the female body as something separate from the inner individual, something which could be managed and changed. The pill was the first step on the road which eventually led to the strange place we now find ourselves in. Whatever you might think of this place, Harrington argues that it’s not feminism. It’s not something that benefits women qua women.

In order to do that, to go back to a feminism that actually benefits women, Harrington recommends several things, including:

Re-embracing the body as something constitutive of the self.

A re-emphasis on marriage and children as a key component to a meaningful life that’s less about self-fulfillment and more about finding fulfillment in relation to others.

Abstaining from birth control, and a rewilding of sex in general.

Restoration of single-sex spaces, particularly for males, but returning the definition of female single sex spaces to be those that don’t include transwomen.

All of these proposals are pretty radical in today’s climate, but number three seems particularly bold. Nevertheless she puts forth a compelling case. And whether you’re convinced by it or not you should nevertheless come away with the sense that birth control is far more transformative than it’s proponents claim, which takes us to:

Eschatological Implications

Perhaps you’ve encountered Nick Bostrom’s Vulnerable World Hypothesis. If you have it might be because I’ve written about it a couple of times, and in fact I have a brand new post on the subject in the works. (Coming Soon!) But as a reminder, here’s his basic idea:

Inventing new technology is like blindly drawing balls from an urn. The balls come in various shades. If you draw white balls that’s good, if you draw gray balls that’s bad, if you ever draw a pure black ball the game is over and humanity is no more. This is an interesting metaphor, but I believe that Bostrom missed a key part of how technologies actually play out. Some balls change their shade after they’re drawn. You might have a ball that was white when it was drawn, but which gradually gets darker. Or more rarely a ball which was gray when drawn but which gradually whitens.

It seems increasingly likely that birth control is one of the balls that has gotten darker the longer it’s out of the urn. Certainly there were people who thought it was a bad idea from the very beginning, but they were mostly viewed as hopelessly reactionary. And in any case they were quickly put in their place by the Supreme Court just a few years after the pill was released. Jump forward to today, and the idea that a Supreme Court case was required to make birth control legal everywhere seems almost unbelievable and definite evidence of a prehistoric, patriarchal past. Most people then and most people now view birth control as an unalloyed good, but when you think about what we’re messing with — the fundamental forces we’re modifying — it seems myopic to have ever assumed that birth control wouldn’t have vast and far reaching second order effects.

Is this a ball that will eventually darken so much that it becomes the pure black ball? Almost certainly not, though humanity can’t survive if it doesn’t reproduce and birth control’s effect on fertility has been massive.

Even if it’s not a pure black ball, Harrington does make the case that it’s a significantly darker ball than most people imagine, and that the long term consequences of its introduction are only just now beginning to be felt.

This takes me to another addition I’ve made to the metaphor of the urns and the balls. It’s possible that even if we never draw a pure black ball, that a sufficient number of dark gray balls would have the same effect. And it would appear that we might have added another one to our pile.

II- Non-Fiction Reviews

Metabolical: The Lure and the Lies of Processed Food, Nutrition, and Modern Medicine

By: Robert H. Lustig

Published: 2021

416 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

That it’s misleading to focus on what’s in the food, the important thing is what’s been done to the food. And it is this processing of food that is responsible for nearly all of our health problems.

What's the author's angle?

Lustig has been talking about the evils of adding sugar to food for the last 15 years, and has been acting as a gadfly towards (as he terms them) “Big Food, Big Pharma, and Big Government” since that time.

Who should read this book?

If you’re interested in a deep dive on diet and nutrition from an academic, scientific and historical perspective then this is a good book. If you’re looking for recommendations on what you should eat, then be warned that this book offers no specific recommendations. If you want to wait I’m planning to read Outlive by Dr. Peter Attia next month which will probably cover similar ground, and might be better.

General Thoughts

This book was fascinating and scary. He makes a powerful case that modern food processing is causing all kinds of problems. But from my perspective he made an equally powerful case that there was very little one could do about it. Much of this impression came from the lack of specific recommendations. He basically never talks about X being a good food. He talks a lot about what good food is and does, but then he also talks about how even food that you might think is good has been processed in such a way that it isn’t. For example there’s no added sugar in meat, so it should be good right? But of course modern meat comes from animals that have been given tons of antibiotics, were fed on corn, and much of it has added nitrates. At the very end of the book he claims it’s easy to eat real food and points people towards foogal.com for recipes, but that’s the extent of it.

Any attempt to review the book suffers because of this approach. If there are hundreds of ways in which processed food is bad, which should I cover? Whatever I decide will be merely scratching the surface. It would be both easier and more productive in this situation to cover his recommendations, but those he offers are too general to be of much use to anyone. He does seem to like fiber (though also claims that insoluble fiber has been removed from most of the food we eat). Beyond that he’s constantly saying that there are only two rules. You need to “feed the gut and protect the liver”. But it would have been really nice if at some point he had said, “The easiest way to do that is to eat more lettuce…” or something similar.

With my whining out of the way, he does make one point that really resonated with me. Oftentimes economists, when confronted with an argument like this, will point out that the processing of food has led to unprecedented abundance. We’ve gone from a world in which people were hungry all the time to one in which they’re actually consuming too many calories. And while this consumption might have some downsides, the cure that Lustig proposes would be worse than the disease. An attempt to ban most forms of processed food would lead to a vast increase in prices, and consequently massive amounts of hunger and, inevitably, starvation.

But for the moment, imagine that Lustig is right and some significant fraction of our out of control medical spending is due to our diet of processed foods. Medical spending is so gigantic (currently almost 19% of GDP) that even if only a quarter of that spending is due to our bad diet, it represents a giant pile of money. Lustig therefore argues that we should be able to route this money towards providing better food, and actually end up ahead, spending less money overall, and being far healthier. I think the implementation of such a plan would be prohibitively complicated. Also Lustig’s estimate for how much health care spending is attributable to poor diet, is higher than my estimate, but all that aside, I think he might be onto something.

Categories

By: Aristotle

Published: Approx. 300 BC

48 Pages

Prior Analytics

By: Aristotle

Published: Approx. 300 BC

119 Pages

Briefly, what are these books about?

Categorizing things using syllogisms. (That’s an oversimplification, but just barely.)

What's the author's angle?

One of the things that I’ve picked up in my study of Aristotle is that more than ethics and logic his true focus appeared to be biology. Particularly the classification of flora and fauna. I think that’s a large part of what he’s angling for in these two books. Or at least if you keep this angle in mind it makes the books easier to understand.

Who should read this book?

That's a good question. Both of these books are pretty dense, but I feel like they also went a long way towards helping me understand, when it comes to Aristotle, what all the fuss is about.

General Thoughts

Part of the problem when dealing with someone who wrote as much and as densely as Aristotle is how much should you read? It’s tempting, but also extremely time-consuming, to just decide to read everything. I may end up doing that, but my basic plan is to read a bit. Ask “Do I feel like I’ve gotten enough Aristotle?” And if the answer is “no”, then I read a bit more. I read the Nicomachean Ethics, and decided that wasn’t enough. So I found a list of the "essential" Aristotle and decided to read those books as well.

There were six of them, so as you can see I haven't made it very far. Both of the books I read in June were very dense. The Categories is basically just what it sounds like, and there isn't a lot of additional meat to it. On the other hand Prior Analytics is all logic and syllogisms.

In addition to the decision of what to read, there’s the decision of how to read. Given the density of these books it could be argued that you should either read them very slowly and carefully, or you should not read them at all. I'll be honest, I didn't read slowly and carefully. Certainly I didn't have a piece of paper out working through the logic examples as Aristotle was presenting them. So was I just wasting my time? I don't think so.

I would argue that someone like Aristotle can be understood at three different levels:

One level would be the level of a student of Aristotle. Someone who's in college and taking a 500 level philosophy course. You would expect them to work through all of the logic problems, read all the footnotes, perhaps even discuss the various ways you could interpret the original ancient Greek of the text.

Another level is someone who wants to understand Aristotle, but assumes that the best way to do that is to have a contemporary person distill out the essence in a form you can understand. Rather than reading Aristotle directly, you read a book about him — perhaps not "Aristotle for Dummies" but something similar.

I believe there is a level between these two. I enjoy reading some smart person's distillation of Aristotle, but also I think there's something about reading the original text that gives you a sense of a thinker that you can't otherwise get just by reading about him. Reading the actual words (albeit translated, reading the original Greek is a bridge too far) gives you a sense of the man you can't otherwise get.

One of the ways of thinking about great books is as a very long conversation, and reading the original makes Aristotle's place in that conversation real in a way that is impossible to duplicate by just reading about him.

The Pumpkin Plan: A Simple Strategy to Grow a Remarkable Business in Any Field

By: Mike Michalowicz

Published: 2012

240 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

That to succeed in business you should focus all of your efforts on your best clients, just as a pumpkin farmer focuses all of his efforts on a single pumpkin.

What's the author's angle?

Michalowicz does seem to genuinely want to help business owners, but he also has a bunch of secondary products for which this book acts as marketing.

Who should read this book?

The general consensus among small business owners of my acquaintance is that time spent reading business books has a positive ROI. If that describes you then I think this book is worth adding to your list.

General Thoughts

Everyone thinks that if businesses have enough customers that they’ll be successful. This is not the case. Certainly that’s the first hurdle most people have to get over, but it’s far from the only one. It’s entirely possible to have plenty of customers, and therefore revenue, but to not be profitable. Michalowicz points out that if you have a lot of customers, and you’re not profitable it’s probably because, while some of your customers are very profitable, others are very unprofitable. If you get rid of these latter customers then your company as a whole will be profitable. Also you’ll get rid of the stress and aggravation that comes from dealing with crappy customers and have more time and energy to care for your best customers — the pumpkins that are going to win the awards.

This book didn’t say anything I hadn’t heard elsewhere, but Michalowicz is an engaging writer and narrator (I listened to the audiobook). Also, even if I’d heard it before it’s the kind of thing that’s important enough that it bears being reminded of, frequently.

Though like many things, this sort of pruning is easier said than done. It can be particularly difficult knowing who should be pruned. Yeah, you’re always going to have one or two clients where this sort of thing is a no brainer, and one or two clients who are clearly very profitable. But there are going to be a lot of clients in the middle where it’s only through rigorous and detailed cost accounting that you’re going to know how profitable they actually are. And it’s always possible that you’ll find that they’re unprofitable, but also, maybe they’re just having a bad month.

All of this is to say that I think Michalowicz sometimes understates the difficulties involved in determining which clients to prune, but that doesn’t mean that pruning is not a good idea.

III- Fiction Reviews

The Butcher's Masquerade (Dungeon Crawler Carl #5)

By: Matt Dinniman

Published: 2022

732 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Another installment in the Dungeon Crawler Carl LitRPG series. In this one Carl and his sentient, talking cat, Princess Donut, not only have to face off against the dungeon and its denizens, but against hunters. What are hunters you ask? They are galactic citizens who pay for the privilege of entering the dungeon to hunt the crawlers. And as you might imagine they’ve got numerous tricks up their sleeves and they don’t like losing.

Who should read this book?

This book was every bit as good as the previous four and Dinniman seems to be quite adept at mixing things up so the plots feel different, while also developing events from previous books in interesting ways. It’s not great literature by any means, but I’ve enjoyed the series so far.

General Thoughts

I assume by this point, if you’ve been following along you have the gist of what this series is about. If not, see here. So I’m going to get a little bit nit picky. One problem that science fiction and fantasy novels often run into is creating a world that’s believable in the absence of the protagonist. The world gets away with doing X to the protagonist because they have plot armor or they have other unique abilities that allow them to overcome X, but if the world does X as the usual tactic the system would quickly collapse.

This usually takes the form of some situation that’s basically unsurvivable. Something where 99% of the time whoever had to face this situation would die. But of course the protagonist always ends up being in the 1%. But if you’re considering the world as a whole you have to imagine what happens if 99% of people die. And frequently a 99% failure rate or a 99% fatality rate would be completely unsustainable. In this series it’s not just Carl that frequently faces 99% fatality situations, but everyone in the dungeon. Now fortunately Carl’s on their side, so they manage to survive, but how do dungeons work in general if every level appears to have a 99% fatality rate?

On the other hand, outside of this complaint Dinniman does a pretty good job of describing how the world works in the absence of the protagonist, with lots of details that give one the sense he’s thought pretty deeply about stuff, so maybe I can forgive him this one oversight in the name of heightening the tension and making it a good story.

Xenocide (The Ender Saga #3)

By: Orson Scott Card

Published: 1991

394 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The further adventures of Andrew “Ender” Wiggins. This time he must manage the relationship between the Formics, the Pequeninos and the humans of Lusitania. With the threat of the destruction of Lusitania itself hanging in the background. Oh and also there’s an AI.

Who should read this book?

If you enjoyed Speaker for the Dead then you might enjoy Xenocide. It’s very similar to Speaker for the Dead, but it gets a lot more hate online.

General Thoughts

In my review of Speaker for the Dead I mentioned that the entire novel flowed from an entirely irrational decision. This is a decision no one would make or if they did, at some point they would realize they were being dumb and change their mind, but if they didn’t then the ensuing events would make a great story. The same thing happens in Xenocide, except it’s never quite as bad as in Speaker, but it happens more than once. Again if you overlook the irrationality of these decisions, what emerges is a very interesting story, but I would say their frequency makes such a suspension more difficult.

I did enjoy the examination of belief in god(s) that formed the core of the Gloriously Bright story. Card does such a good job examining the potential irrationality of such belief that if one didn’t know they might assume he was an atheist.

In any event the whole point of re-reading the three books is so that I could read Children of the Mind. That book is up next, though I confess to being nervous, its GoodReads ranking is even lower than Xenocide’s…

When We Cease to Understand the World

by: Benjamin Labatut

Published: 2021

192 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

A series of stories about famous physicists and mathematicians with lots of truth and a significant amount of fiction.

Who should read this book?

Imagine reading mini-biographies of some great mathematicians and physicists but set in a slightly different world than ours. This other world is one of Lovecraftian madness and Elder Gods where delving too deeply into math and physics puts you in touch with the underlying madness. If that sounds really cool, then this is the book for you.

General Thoughts

This book is hard to describe. You have largely factual accounts of the lives of certain scientists, with little bits of fiction thrown in, though the amount of fiction that gets thrown in scales as the book progresses. The fictional bits seem designed to increase the intensity of the story, but also to give the story a moral. That moral, as illustrated by the title of the book, mostly seems to be that we have passed the point where scientific discovery is illuminating. The deepest secrets of the universe are strange — beyond the capacity of our limited intellects. And if we stare too deeply into the abyss the only thing we will find is madness.

The Sandman: Book Three (The Sandman #3)

By: Neil Gaiman

Published: Original Comic book was 1990

560 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The further adventures of Morpheus. This collection is equal parts an expansion of the Sandman universe and collection of short stories in Gaiman's unique style.

Who should read this book?

Anyone who enjoyed the first two collections (reviewed here and here) and anyone who just enjoys Gaiman in general.

General Thoughts

This collection might not be quite as good as the 2nd collection, but it was close. And better than the first collection. I've already discussed the two dominant storylines. (To go any deeper would be to spoil things.)

I was reading this while on my cruise. At one point I was doing so out on the roof deck and someone walked by and asked me how it was. He said he was a big fan of Gaiman, but that he hadn't read any Sandman. That exactly described me as of a few months ago, and I’m glad I decided to finally pick it up, and I’m sure you’ll feel the same. That is, if for some reason, you also fit into that same narrow category.

IV- Religious Reviews

The New Jerusalem

By: G. K. Chesterton

Published: 1920

190 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Chesterton travels through the Middle East and to Jerusalem, remarking on things and people along the way.

Who should read this book?

At some point I acquired a collection of 50 Chesterton books on my kindle, and I’ve been gradually working my way through them. If you’re not trying to be a completist in the same fashion I am, then this is probably one of the one’s I would skip.

General Thoughts

This book was written shortly after the Balfour Declaration, so much of what Chesterton says concerns the phenomenon of Zionism and the place of Jews in Palestine in relation to everyone else. It is interesting as an observation of that period, but perhaps too close to the transition to be entirely useful.

I said this is a book I would skip, but even so Chesterton manages to still pack in some great observations. So I thought I’d include a few:

That is the real lesson that the enlightened traveller should learn; the lesson about himself. That is the test that should really be put to those who say that the Christianity of Jerusalem is degraded. After a thousand years of Turkish tyranny, the religion of a London fashionable preacher would not be degraded. It would be destroyed. It would not be there at all, to be jeered at by every prosperous tourist out of a train de luxe. It is worth while to pause upon the point; for nothing has been so wholly missed in our modern religious ideals as the ideal of tenacity. Fashion is called progress. Every new fashion is called a new faith. Every faith is a faith which offers everything except faithfulness.

That one definitely seems to sum up the problem with abundance and plenty. When you’re Christians trapped in the middle of a hostile nation, you can hold on to your faith forever. But put Christians in a modern developed country and they can barely hold on to their faith for more than a couple generations.

But my sympathies are generally, I confess, with the impotent and even invisible majority. And my sympathies, when I go beyond the things I myself believe, are with all the poor Jews who do believe in Judaism and all the Mahometans who do believe in Mahometanism, not to mention so obscure a crowd as the Christians who do believe in Christianity.

A crowd that gets more obscure by the minute.

Any suggestion that progress has at any time taken the wrong turning is always answered by the argument that men idealise the past, and make a myth of the Age of Gold. If my progressive guide has led me into a morass or a man-trap by turning to the left by the red pillar-box, instead of to the right by the blue palings of the inn called the Rising Sun, my progressive guide always proceeds to soothe me by talking about the myth of an Age of Gold. He says I am idealising the right turning. He says the blue palings are not so blue as they are painted. He says they are only blue with distance. He assures me there are spots on the sun, even on the rising sun. Sometimes he tells me I am wrong in my fixed conviction that the blue was of solid sapphires, or the sun of solid gold. In short he assures me I am wrong in supposing that the right turning was right in every possible respect; as if I had ever supposed anything of the sort. I want to go back to that particular place, not because it was all my fancy paints it, or because it was the best place my fancy can paint; but because it was a many thousand times better place than the man-trap in which he and his like have landed me. But above all I want to go back to it, not because I know it was the right place but because I think it was the right turning. And the right turning might possibly have led me to the right place; whereas the progressive guide has quite certainly led me to the wrong one.

You’d hardly believe that this was written in 1920 so accurately does it describe the same debates we’re having right this very minute.