Tetlock, the Taliban, and Taleb

If you prefer to listen rather than read, this blog is available as a podcast here. Or if you want to listen to just this post:

I.

There have been many essays written in the aftermath of our withdrawal from Afghanistan. One of the more interesting was penned by Richard Hanania, and titled “Tetlock and the Taliban”. Everyone reading this has heard of the Taliban, but there might be a few of you who are unfamiliar with Tetlock. And even if that name rings a bell you might not be clear on what his relation is to the Taliban. Hanania himself apologizes to Tetlock for the association, but “couldn’t resist the alliteration”, which is understandable. Neither could I.

Tetlock is known for a lot of things, but he got his start by pointing out that “experts” often weren’t. To borrow from Hanania:

Phil Tetlock’s work on experts is one of those things that gets a lot of attention, but still manages to be underrated. In his 2005 Expert Political Judgment: How Good Is It? How Can We Know?, he found that the forecasting abilities of subject-matter experts were no better than educated laymen when it came to predicting geopolitical events and economic outcomes.

From this summary the connection to the Taliban is probably obvious. This is an arena where the subject matter experts got things very wrong. Hanania’s opening analogy is too good not to quote:

Imagine that the US was competing in a space race with some third world country, say Zambia, for whatever reason. Americans of course would have orders of magnitude more money to throw at the problem, and the most respected aerospace engineers in the world, with degrees from the best universities and publications in the top journals. Zambia would have none of this. What should our reaction be if, after a decade, Zambia had made more progress?

Obviously, it would call into question the entire field of aerospace engineering. What good were all those Google Scholar pages filled with thousands of citations, all the knowledge gained from our labs and universities, if Western science gets outcompeted by the third world?

For all that has been said about Afghanistan, no one has noticed that this is precisely what just happened to political science.

Of course Hanania’s point is more devastating than Tetlock’s. The experts weren’t just “no better” than the Taliban’s “educated laymen”. The “experts” were decisively outcompeted despite having vastly more money and in theory, all the expertise. Certainly they had all the credentialed expertise...

In some ways Hanania’s point is just a restatement of Antonio García Martínez’s point, which I used to end my last post on Afghanistan—the idea we are an unserious people. That we enjoy “an imperium so broad and blinding” we’ve never been “made to suffer the limits of [our] understanding or re-assess [our] assumptions about [the] world”

So the Taliban needed no introduction, and we’ve introduced Tetlock, but what about Taleb? Longtime readers of this blog should be very familiar with Nassim Nicholas Taleb, but if not I have a whole post introducing his ideas. For this post we’re interested in two things, his relationship to Tetlock and his work describing black swans: rare, consequential and unpredictable events.

Taleb and Tetlock are on the same page when it comes to experts, and in fact for a time they were collaborators, co-authoring papers on the fallibility of expert predictions and the general difficulty of making predictions—particularly when it came to fat-tail risks. But then, according to Taleb, Tetlock was seduced by government money and went from pointing out the weaknesses of experts to trying to supplant them, by creating the Good Judgement project, and the whole project of superforecasting.

The key problem with expert prediction, from Tetlock’s point of view, is that experts are unaccountable. No one tracks whether they were eventually right or wrong. Beyond that, their “predictions” are made in such a way that even making a determination of accuracy is impossible. Additionally experts are not any better at prediction than educated laypeople. Tetlock’s solution is to offer the chance for anyone to make predictions, but in the process ensure that the predictions can be tracked, and assessed for accuracy. From there you can promote those people with the best track record. A sample prediction might be “I am 90% confident that Joe Biden will win the 2020 presidential election.”

Taleb agreed with the problem, but not with the solution. And this is where black swans come in. Black swans can’t be predicted, they can only be hedged against, and prepared for, but superforecasting, by giving the illusion of prediction, encourages people to be less prepared for black swans, and in the end worse off than they would have been without the prediction.

In the time since writing The Black Swan Taleb has come to hate the term, because people have twisted it into an excuse for precisely the kind of unpreparedness he was trying to prevent.

“No one could have done anything about the 2007 financial crisis. It was a black swan!”

“We couldn’t have done anything about the pandemic in advance. It was a black swan!”

“Who could have predicted that the Taliban would take over the country in nine days! It was a black swan!”

Accordingly, other terms have been suggested. In my last post I reviewed a book which introduced the term “gray rhino”, something people can see coming, but which they nevertheless ignore.

Regardless of the label we decide to apply to what happened in Afghanistan, it feels like we were caught flat footed. We needed to be better prepared. Taleb says we can be better prepared if we expect black swans. Tetlock says we can be better prepared by predicting what to prepare for. Afghanistan seems like precisely the sort of thing superforecasting was designed for. Despite this I can find no evidence that Tetlock’s stable of superforecasters predicted how fast Afghanistan would fall, or any evidence that they even tried.

As a final point before we move on. This last bit is one of the biggest problems with superforecasting. The idea that you should only be judged for what you got wrong, that if you were never asked to make a prediction about something that the endeavor “worked”. But reality doesn’t care about what you chose to make predictions on vs. what you didn’t. Reality does whatever it feels like. And the fact that you didn’t choose to make any predictions about the fall of Afghanistan doesn’t mean that thousands of interpreters didn’t end up being left behind. And the fact that you didn’t choose to make any predictions about pandemics doesn’t mean that millions of people didn’t die. This is the chief difference between Tetlock and Taleb.

II.

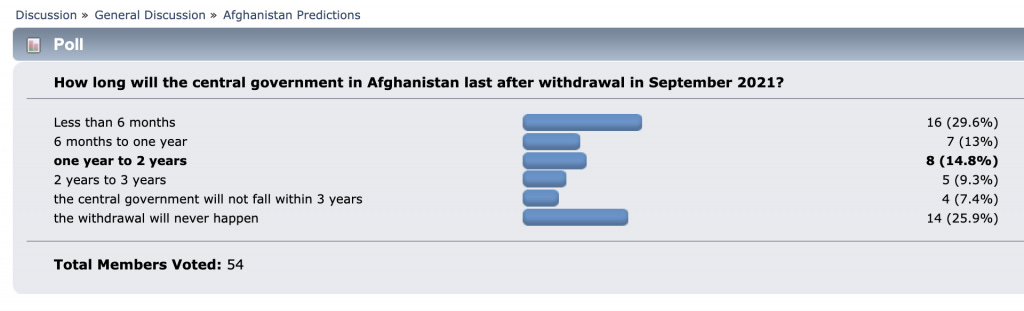

I first thought about this issue when I came across a poll on a forum I frequent, in which users were asked how long they thought the Afghan government would last. The options and results were:

(In the interest of full disclosure the bolded option indicates that I said one to two years.)

While it is true that a plurality of people said less than six months, six months was still much longer than the nine days it actually took (from capturing the first provincial capital to the fall of Kabul) and from the discussion that followed the poll, it seemed most of those 16 people were thinking that the government would fall at closer to six months or even three months than one week. In fact the best thing, prediction-wise, to come out of the discussion was when someone pointed out that 10 years previously The Onion had posted an article with the headline U.S. Quietly Slips Out Of Afghanistan In Dead Of Night, which is exactly what happened at Bagram.

As it turns out this is not the first time The Onion has eerily predicted the future. There’s a whole subgenre of noticing all the times it’s happened. How do they do it? Well of course part of the answer is selection bias. No one is expecting them to predict the future; nobody comments on all the articles that didn't come true. But when one does, it’s noteworthy. But I think there’s something else going on as well: I think they come up with the worst or most ridiculous thing that could happen, and because of the way the world works, some of the time that’s exactly what does happen.

Between the poll answers being skewed from reality and the link to the Onion article, the thread led me to wonder: where were the superforecasters in all of this?

I don’t want to go through all of the problems I’ve brought up with superforecasting (I’ve easily written more than 10,000 words on the subject) but this event is another example of nearly all of my complaints.

There is no methodology to account for the differing impact of being incorrect on some predictions vs. others. (Being wrong about whether the Tokyo Olympics will be held is a lot less consequential than being wrong about Brexit.)

Their attention is naturally drawn to obvious questions where tracking predictions is easy.

Their rate of success is skewed both by only picking obvious questions, and by lumping together both the consequential and the inconsequential.

People use superforecasting as a way of more efficiently allocating resources, but efficiency is essentially equal to fragility, which leaves us less prepared when things go really bad. (It was pretty efficient to just leave Bagram all at once.)

Or course some of these don’t apply because as far as I can tell the Good Judgment project and it’s stable of superforecasters never tackled the question, but they easily could have. They could have had a series of questions about whether the Taliban would be in control of Kabul by a certain date. This seems specific enough to meet their criteria. But as I said, I could find no evidence that they had. Which means either they did make such predictions and were embarrassingly wrong, so it’s been buried, or despite its geopolitical importance it never occurred to them to make any predictions about when Afghanistan would fall. (But it did occur to a random poster on a fringe internet message board?) Both options are bad.

When people like me criticize superforecasting and Tetlock’s Good Judgment project in this manner, the common response is to point out all the things they did get right and further that superforecasting is not about getting everything right; it’s about improving the odds, and getting more things right than the old method of relying on the experts. This is a laudable goal. But as I point out it suffers from several blindspots. The blindspot of impact is particularly egregious and deserves more discussion. To quote from one of my previous posts where I reflected on their failure to predict the pandemic:

To put it another way, I’m sure that the Good Judgement project and other people following the Tetlockian methodology have made thousands of forecasts about the world. Let’s be incredibly charitable and assume that out of all these thousands of predictions, 99% were correct. That out of everything they made predictions about 99% of it came to pass. That sounds fantastic, but depending on what’s in the 1% of the things they didn’t predict, the world could still be a vastly different place than what they expected. And that assumes that their predictions encompass every possibility. In reality there are lots of very impactful things which they might never have considered assigning a probability to. That in fact they could actually be 100% correct about the stuff they predicted but still be caught entirely flat footed by the future because something happened they never even considered.

As far as I can tell there were no advance predictions of the probability of a pandemic by anyone following the Tetlockian methodology, say in 2019 or earlier. Or any list where “pandemic” was #1 on the “list of things superforecasters think we’re unprepared for”, or really any indication at all that people who listened to superforecasters were more prepared for this than the average individual. But the Good Judgement Project did try their hand at both Brexit and Trump and got both wrong. This is what I mean by the impact of the stuff they were wrong about being greater than the stuff they were correct about. When future historians consider the last five years or even the last 10, I’m not sure what events they will rate as being the most important, but surely those three would have to be in the top 10. They correctly predicted a lot of stuff which didn’t amount to anything and missed predicting the few things that really mattered.

Once again we find ourselves in a similar position. When we imagine historians looking back on 2021, no one would find it surprising if they ranked the withdrawal of the US and subsequent capture of Afghanistan by the Taliban as the most impactful event of the year. And yet superforecasters did nothing to help us prepare for this event.

IV.

The natural next question is to ask how should we have prepared for what happened? Particularly since we can’t rely on the predictions of superforecasters to warn us. What methodology do I suggest instead of superforecasting? Here we return to the remarkable prescience of The Onion. They ended up accurately predicting what would happen in Afghanistan 10 years in advance, by just imagining the worst thing that could happen. And in the weeks since Kabul fell, my own criticism of Biden has settled around this theme. He deserves credit for realizing that the US mission in Afghanistan had failed, and that we needed to leave, that in fact we had needed to leave for a while. Bad things had happened, and bad things would continue to happen, but in accepting the failure and its consequences he didn’t go far enough.

One can imagine Biden asserting that Afghanistan and Iraq were far worse than Bush and his “cronies” had predicted. But then somehow he overlooked the general wisdom that anything can end up being a lot worse than predicted, particularly in the arena of war (or disease). If Bush can be wrong about the cost and casualties associated with invading Afghanistan, is it possible that Biden might be wrong about the cost and casualties associated with leaving Afghanistan? To state things more generally, the potential for things to go wrong in an operation like this far exceeds the potential for things to go right. Biden, while accepting past failure, didn’t do enough to accept the possibility of future failure.

As I mentioned, my answer to the poll question of how long the Afghanistan government was going to last was 1-2 years. And I clearly got it wrong (whatever my excuses). But I can tell you what questions I would have aced (and I think my previous 200+ blog posts back me up on this point):

Is there a significant chance that the withdrawal will go really badly?

Is it likely to go worse than the government expects?

And to be clear I’m not looking to make predictions for the sake of predictions. I’m not trying to be more accurate, I’m looking for a methodology that gives us a better overall outcome. So is the answer to how we could have been better prepared, merely “More pessimism?” Well that’s certainly a good place to start, beyond that there’s things I’ve been talking about since the blog was started. But a good next step is to look at the impact of being wrong. Tetlock was correct when he pointed out that experts are wrong most of the time. But what he didn’t account for is it’s possible to be wrong most of the time, but still end up ahead. To illustrate this point I’d like to end by recycling an example I used the last time I talked about superforecasting:

The movie Molly’s Game is about a series of illegal poker games run by Molly Bloom. The first set of games she runs is dominated by Player X, who encourages Molly to bring in fishes, bad players with lots of money. Accordingly, Molly is confused when Player X brings in Harlan Eustice, who ends up being a very skillful player. That is until one night when Eustice loses a hand to the worst player at the table. This sets him off, changing him from a calm and skillful player, into a compulsive and horrible player, and by the end of the night he’s down $1.2 million.

Let’s put some numbers on things and say that 99% of the time Eustice is conservative and successful and he mostly wins. That on average, conservative Eustice ends the night up by $10k. But, 1% of the time, Eustice is compulsive and horrible, and during those times he loses $1.2 million. And so our question is should he play poker at all? (And should Player X want him at the same table he’s at?) The math is straightforward, his expected return over 100 games is -$210k. It would seem clear that the answer is “No, he shouldn’t play poker.”

But superforecasting doesn’t deal with the question of whether someone should “play poker” it works by considering a single question, answering that question and assigning a confidence level to the answer. So in this case they would be asked the question, “Will Harlan Eustice win money at poker tonight?” To which they would say, “Yes, he will, and my confidence level in that prediction is 99%.”

This is what I mean by impact. When things depart from the status quo, when Eustice loses money, it’s so dramatic that it overwhelms all of the times when things went according to expectations.

Biden was correct when he claimed we needed to withdraw from Afghanistan. He had no choice, he had to play poker. But once he decided to play poker he should have done it as skillfully as possible, because the stakes were huge. And as I have so frequently pointed out, when the stakes are big, as they almost always are when we’re talking about nations, wars, and pandemics, the skill of pessimism always ends up being more important than the skill of superforecasting.

I had a few people read a draft of this post. One of them complained that I was using a $100 word when a $1 word would have sufficed. (Any guesses on which word it was?) But don’t $100 words make my donors feel like they’re getting their money’s worth? If you too want to be able to bask in the comforting embrace of expensive vocabulary consider joining them.