Radical Reform and the Three Kinds of Complexity

If you prefer to listen rather than read, this blog is available as a podcast here. Or if you want to listen to just this post:

I.

The debate I’ve been engaged in over the last several posts continues. The latest salvo is a post from Scott Alexander titled: The Consequences Of Radical Reform. It opens as follows:

The thread that runs from Edmund Burke to James Scott and Seeing Like A State goes: systems that evolve organically are well-adapted to their purpose. Cultures, ancient traditions, and long-lasting institutions contain irreplaceable wisdom. If some reformer or technocrat who thinks he's the smartest guy in the room sweeps them aside and replaces them with some clever theory he just came up with, he'll make everything much worse. That's why collective farming, Brasilia, and Robert Moses worked worse than ordinary people doing ordinary things.

Alexander then goes on to disagree with this narrative, and in support of this disagreement he offers up a new piece of evidence, a study from 2009 (which he only recently came across) which compares the European territories where the Napoleonic Code was imposed vs. those where it was not. Basically those territories conquered by Napoleon vs. the one’s a little bit farther along his line of advance which weren’t. The study shows that, in terms of economic growth, urbanization, etc. The former did better. If we then go on to define imposition of the Napoleonic Code to be an example of radical reform, then we have the answer to our perennial question. This is proof that, to adapt Alexander’s original statement:

[A] technocrat who thinks he's the smartest guy in the room [can] sweep [traditional laws] aside and replace them with some clever theory he just came up with [and] he'll make everything much… Better!

Now to be clear I don’t think Alexander is offering this up as some sort of “game, set, match” for the whole debate. But increasingly he has been taking the position that technocrats, on balance, make things better not worse. This study is evidence of that, and it appears to push him farther in that direction. Of course, if you’ve been following along, my contention has been the opposite: that on balance technocrats do make things worse. Though once again, this is on balance, I have never claimed that technocrats never get anything right or have any successes, and in the course of this post we’ll get to some of those successes. But first...

II.

Let’s establish what we’re talking about. Get a sense of what we’re debating and what the stakes are. In essence this is a discussion about societies, cultures, and civilizations at the highest level. We’re evaluating their success when everything is taken into account, not merely as a snapshot of a single point in time but their success over decades and centuries. Civilizations are enormously complex, and essentially this is a debate about how to manage that complexity. On the one side of our debate we have cultural evolution. (Alexander puts forth Seeing Like a State, but for me the more pertinent corpus is Henrich’s books, Secret of our Success and WEIRDEST People in the World.) On the other side of the debate we have technocrats and rational planning. (Represented by? Enlightenment Now? Anything else?)

Of course, reducing it to two sides overlooks the possibility of other civilizational-level organizing principles, as well as a blending of technocracy and cultural evolution, both options which are outside the scope of this post. Though the latter is an interesting idea, and worth exploring, particularly if technocrats were content to stick with the things they’re good at, and refrain from interfering in areas where they’re less successful. But I have seen little evidence of such a willingness to forebear particularly recently.

Having identified the two sides of the debate the next step is to define them. How do we distinguish between the two? While initially this might seem straightforward, once you dig in, the line dividing them is not as bright as one might think. Under cultural evolution a person comes up with an idea. If the idea is an improvement on what was being done before it spreads to other people, eventually becoming part of the cultural package.

Under technocracy an expert comes up with an idea. If the idea is an improvement on what was being done before it spreads to other governments eventually becoming part of the toolkit of “best practices”.

Stated that way the difference doesn’t seem all that great. I just swapped out a few words, and is there really that much difference between “person” and “expert” or “other people” and “government”? As a matter of fact I would argue that there is, that within these slightly different words lies the entire debate. Let’s start with “government”.

There is of course the standard libertarian argument that governments are different because they use force to get you to do things, whereas cultural evolution is presumably voluntary, or at least more voluntary than a modern state. This may be true, but I don’t think it’s a difference worth spending much time on. Particularly historically, cultures also carried a huge amount of weight. And, for the person experiencing it, the difference between being shunned by an entire community vs. policemen showing up at your door is probably not all that great.

No, I think the primary difference between how technocracies implement new programs and the way that cultures evolve is a difference of scale and speed. Historically cultural evolution took place in small groups—extended families or tribes—and thus whatever the innovation was, at best it would be adopted by a few hundred people. The success of the innovation would be reflected, in part, by a greater number of offspring, which also provides a mechanism for spreading the innovation. Eventually this gets to the point where the successful culture starts displacing, absorbing or eliminating less successful ones. Beyond the foregoing other things might make the innovation spread more quickly, but at best the whole thing scales up over the course of years if not decades.

On the other hand, with a technocracy, change can be implemented across millions of people conceivably overnight—a speed and scale which is vastly greater. As an example, consider prohibition—a very progressive idea, in a very progressive age. One day booze was legal for 100 million people and the next day it wasn’t. Now there were plenty of scofflaws, but in some respects the battle it created between bootleggers and the police was the bigger story than the fact that alcohol was illegal, and equally a consequence of the technocratic implementation, which came at the stroke of a pen. Now yes, this stroke was preceded by a 394 day ratification process, and that was preceded by decades of effort by the temperance movement, but this is precisely my point. The 394 days the government spent on it accomplished something at a speed and on a scale that decades of attempts to change the culture couldn’t duplicate.

It should also be noted that scale and speed work in both directions. The government is pretty good at changing things, but it’s even better at preventing things from changing. And here we turn back to Alexander’s post, and the way people imagine technocracy will work—when it’s working well. In particular its superiority to vetocracy

[E]ntrenched interests are constantly blocking necessary change. If only there were some centralized authority powerful enough to sweep them away and do all the changes we know we need, everything would be great.

Vetocracies block the necessary changes. While technocracies presumably don’t allow such vetoes, and are consequently able to make “all the changes we know we need”. Even if we grant that this is a practical description of how technocracies work, rather than just an aspirational one, those words “we know'' are doing a lot of work. Who are “we”? And how do we “know”? Which takes us to...

III.

The other key difference between the definitions of cultural evolution and technocracy was replacing “people” with “experts”. This switch presumably comes because most of our problems are problems of complexity. If the world is complicated then it seems logical that we need experts to understand it. But is this in fact the case? I will certainly grant the first part—the world is complicated—it’s the second part I’m not sure about. To put it another way, we’re not debating the existence of complexity we’re debating how best to deal with it.

Part of the problem is that complexity comes in many different flavors. There is complexity which has existed for as long as humans have (and perhaps longer), like what to do in a given environment so you don’t die. There is complexity which is brand new, like how best to manage social media. And then there is presumably lots of complexity in between that. The kind of complexity that came with nuclear weapons, the invention of the printing press or even the neolithic revolution. So when someone claims that experts are better at dealing with complexity, which sort of complexity are they talking about? All of the above? Just recent complexity? Or some other combination?

Let’s return to the paper referenced by Alexander. Here’s the abstract:

The French Revolution of 1789 had a momentous impact on neighboring countries. The French Revolutionary armies during the 1790s and later under Napoleon invaded and controlled large parts of Europe. Together with invasion came various radical institutional changes. French invasion removed the legal and economic barriers that had protected the nobility, clergy, guilds, and urban oligarchies and established the principle of equality before the law. The evidence suggests that areas that were occupied by the French and that underwent radical institutional reform experienced more rapid urbanization and economic growth, especially after 1850. There is no evidence of a negative effect of French invasion. Our interpretation is that the Revolution destroyed (the institutional underpinnings of) the power of oligarchies and elites opposed to economic change; combined with the arrival of new economic and industrial opportunities in the second half of the 19th century, this helped pave the way for future economic growth. The evidence does not provide any support for several other views, most notably, that evolved institutions are inherently superior to those 'designed'; that institutions must be 'appropriate' and cannot be 'transplanted'; and that the civil code and other French institutions have adverse economic effects.

(I kept thinking I could get away with only quoting part of the abstract, but in the end it was apparent that I was going to end up referencing it all.)

First we can clearly see the speed and scale mentioned in part II. But what about complexity? While not mentioned directly, the complexity referred to by this paper is clearly that brought on by the industrial revolution, so very recent complexity. (If you just do a google search for industrial revolution time period the info box says 1760-1840.) So best case, of the three types of complexity there are, this study represents one point of data for radical reform being better at dealing with new complexity. But there are numerous caveats even to this conclusion.

First it’s pretty straightforward to see that “nobility, clergy, guilds, and urban oligarchies” are the people most likely to object to anything with the word “revolution” in the title, since they’re almost certainly the one’s benefiting from the status quo. Second it didn’t require visionary reformers or rarified experts to see that the industrial revolution would result in economic growth and urbanization, any unbiased observer could see it. Britain had already shown it could be done, so I’m not sure how radical these reforms really were. In other words, the bits that radical reform got right were not that complicated. This is not to say that the industrial revolution wasn’t complicated. It was horribly complicated. It introduced the complications of child labor, pollution, job losses for skilled workers and all manner of social unrest. (Note the widespread revolutions of 1848.)

It’s therefore worth asking which institutions did better with the true complications brought on by the industrial revolution. The institutions these countries got from cultural evolution: monogamy, christianity, literacy? (At least according to WEIRDest People in the World) Or the things they got from technocracy: accelerated growth, elite destruction and equality before the law? I would lean towards the former, but at a minimum this question would seem to be a least as important as the one the paper actually addressed.

It might be useful to examine a current situation with several parallels to the industrial revolution, moving jobs over sea and automation. Once again this is something that the experts/technocrats/globalists have been almost universally in favor of. And again the benefits to doing so were obvious, lower labor costs, cheaper goods, etc. While the associated complexities were mostly ignored until they got too big to be ignored. I think there’s a good case to be made that one of the biggest of these complexities is the opioid epidemic which rages among the people who used to do the jobs that got moved out of the country. Admittedly this is probably a third order effect of the initial outsourcing, but it’s precisely second and third order effects that experts are bad at dealing with. Further, rather than helping mitigate the problem of opioids, there’s a strong case to be made that the experts were one of the key factors in exacerbating it. (For the full story on that see the previous post I did on that subject.)

None of the foregoing is meant to represent my own “game, set, match” in this debate, but rather to remind people that it’s not enough to compare two things on a few selected issues, we have to compare them in their entirety. I’m sympathetic to arguments that cheap goods might help those displaced by offshoring more than they were harmed by the job losses associated with that same offshoring. But it seems apparent that what technocracies and “experts” are really good at is noticing obvious benefits, and implementing changes to capture those benefits rapidly and at scale, of plucking low hanging fruit from the Tree of Recent Technological Progress, but ignoring the pesticides necessary to grow that tree.

Or to use another analogy I heard once, they may be picking up nickels in front of steamrollers...

IV.

We’ve talked quite a bit about recent complexity, which I’m using to cover those things which have shown up in the last several decades or so, but not much about complexity which has been around for longer than that. Earlier, I divided complexity up into three categories, but the divisions are obviously pretty arbitrary, and it might be useful to split them into different buckets, but let’s see where we get with the three buckets I started with.

The oldest source of complexity is the natural world, and human’s relationship to it. One would put things like diet, reproduction, and really anything that impacts evolutionary fitness into this bucket. So what is the best way to deal with this complexity? Well, one imagines that given how long these things have been challenges for humans, we have probably developed genetic adaptations for dealing with this complexity, and it’s probably just best to stand back and let these adaptations do their thing. It’d be nice if it were so simple, and to a certain extent it is, but it’s clear more recent complexity has made the adaptations we’ve built for dealing with long term complexity less effective.

Diet is a great example of all these factors in action. One assumes that there is a diet we’re adapted to. (Though there is a lot of argument over what that diet might be, an argument I’m not qualified to weigh in on.) But then along comes the USDA (read experts/technocrats) with the food pyramid, which provides an authoritative answer to what diet is appropriate. But I think it’s become clear that this is one of those complex areas where experts were not better, and recently the food pyramid has come in for all sorts of criticism, some probably justified some not.

Then as an even more extreme example, there’s the story from a few years back about how in the 60’s the sugar industry paid scientists to demonize fat, instead of sugar, a mistake we’re still grappling with. Which is not to say that this is an easy problem, that’s precisely the point, it’s a devilish complicated one which modernity has exacerbated. For example, it’s clear that evolution has all sorts of tools to draw on in cases of food scarcity, but that never having had to grapple with long term food abundance and variety, it’s terrible at protecting us from that. This particular phenomenon has been labeled supernormal stimuli, and I wrote a whole post on it if you want more details, but I could certainly see an argument that this is an area where evolution and even tradition is fairly useless, because the situation is entirely novel. But of course that is the debate: are experts, through the medium of radical reform, better at this sort of thing or not?

Even with something as novel as supernormal stimuli, tradition is not entirely powerless. Fasting is very traditional and there’s good evidence that it helps with this issue. Also I’ve seen very little evidence that top-down interventions have made any impact on obesity. While diets that involve individuals listening to the evolutionary adaptations they were born with seem to work pretty well.

The upshot of all this is that it’s possible radical reform might help with some of the recent complexity which has been introduced. Even in areas where for a long time we were able to just rely on the adaptations evolution had provided us with, but… I haven’t seem much evidence of radical reform being applied in this fashion, and even less evidence of such a reform working.

Next there’s all the complexity which isn’t recent, but also hasn’t been around so long that we expect a solution to have been encoded in our genes. The area where if there have been adaptations they would have been cultural adaptations, and consequently where you would expect cultural evolution to have the most impact. But also the area where it’s possible that semi-random cultural evolution did not come up with a solution as good as what a team of modern experts could come up with.

Most people have no problem accepting the utility of understanding what our hunter-gatherer ancestors ate. They may have different answers when asked what food that actually was, but they’re united in thinking that the answer is beneficial. As in there’s quite a bit of consensus that genetic adaptations are generally beneficial. As we get closer to the present day this unity disappears. As in there’s not nearly as much consensus that cultural adaptations are beneficial. Thus the fact that the Catholic Church and indeed most religions have been pushing the idea of sexual abstinence outside of marriage for thousands of years carries very little weight. That all it took was the sexual revolution to decide that was a dumb idea.

I’m not sure why people are willing to give so much weight to one kind of evolution, and so little weight to the other kind. It seems naive on its face, even if there weren’t books like the recently reviewed WEIRDest People in the World which spends hundreds of pages contradicting the idea. But of course some of this thinking seems to operate on separate tracks. People will view the forced imposition of the Napoleonic Code as a successful experiment with technocracy, but not view the sexual revolution as a similar technocratic experiment. And certainly it seems more technocratic to impose something from the top down, but once you account for the policies, legal rulings, and general sympathies of the technocratic class. It’s hard to argue that they are not conducting a similar experiment with modern sexual mores.

To be fair I’m sure it doesn’t look like they’re imposing something. I’m sure it looks like they’re allowing something, and the distinction is an important one, though the difference between the two is not as great as you might think, particularly if technocrats use the power of government and the speed and scale we mentioned earlier to force other people to allow it.

V.

Pulling all of the above together, what sort of conclusions can we draw? It would seem to me that the most difficult complexity to deal with is recent complexity, in that it generally disrupts the methods already in place to deal with long term complexity. That said even though recent complexity is where we should be focusing our attention, and where normal evolution and cultural evolution have done the least to prepare us, it’s still not clear that technocracy is obviously better at dealing with these new challenges.

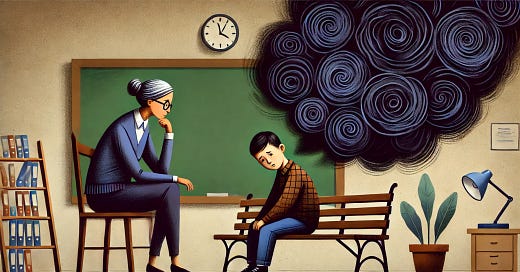

I’ve already given two examples where this might be the case. First, with the underlying complexities of the industrial revolution and second the way the opioid epidemic connects to the process of sending jobs to other countries. Let’s look at one more that’s probably closer to home for most of my readers. The problems associated with social media, a huge unforeseen complexity brought on by the internet. What have the experts/technocrats done to rein in this problem? What do they propose to do? How will that help the teenagers who suffer from social-media linked depression? The grandmas who fall into echo-chambers of extremism? Or help us restore civility to the public sphere?

So far if you’re anything like me you’ve been unimpressed with governmental efforts to deal with the complexities brought on by social media. And you may think, given how recent of a phenomenon it is, that traditional adaptations and institutions would be equally powerless to deal with it. But my sense is this is not the case. That having two supportive parents helps out a great deal. That regular church attendance lowers the risk of depression. And that many “primitive” things like sunlight, physical activity, and seeing people face to face (something which has taken a big hit over the last year) work quite well in dealing with negative effects of social media. They also probably increase the chances that social media will be a positive thing.

My conclusion would be that radical reform might be superior at dealing with recent complexity in certain narrow cases. That occasionally technology opens a new path to some obvious improvement, and in those cases experts/technocrats may be better at hastening the implementation of that improvement. But I think such wins are infrequent. Far more often the improvements brought on by technology are obvious and straight forward but the downsides are complex and opaque, and in focusing on the improvements the experts do nothing to mitigate the downsides. That in these cases—and in cases where we are dealing with long standing complexities—evolutionary adaptations, both natural and cultural, generally perform better.

As one final thought, I want you to conduct a civilization pre-mortem. A pre-mortem is a tactic frequently used by businesses which asks people, at the start of a project, to imagine that it has failed, and then imagine why that might be, so that failure points obvious enough to be summoned up before the project has even started can be mitigated in advance. I want you to take this same methodology and apply it to civilization. If it ends up failing, what will have caused it? Will it have failed because we were too cautious about implementing radical reform? Or will it have failed because we were too aggressive in that endeavor? To look at it from the other side, are long standing adaptations more likely to cause the failure of society or are they more likely to prevent it?

Asking for patronage is actually a very old adaptation to the problem of supporting writers you like, or at least those whose work you think is important. If you like the idea of solving complex problems with long standing adaptations you should like donating to my patreon.