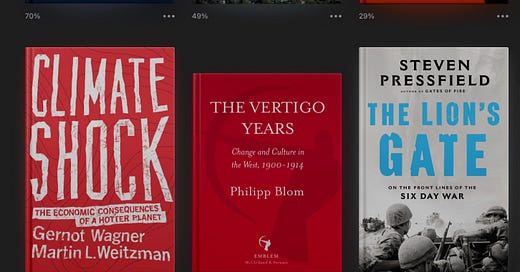

Mid-length Non-fiction Book Reviews: Volume 5

Preference falsification, Anti-War on Terror, Solzhenitsyn, climate warnings, the years before World War I, and the Six-Day War.

Private Truths, Public Lies: The Social Consequences of Preference Falsification by: Timur Kuran

Enough Already: Time to End the War on Terrorism by: Scott Horton

The Gulag Archipelago [Volume 1]: An Experiment in Literary Investigation (1918-1956) by: Alekandr Solzhenitsyn

Climate Shock: The Economic Consequences of a Hotter Planet by: Gernot Wagner & Martin L. Weitzman

The Vertigo Years: Europe 1900-1914 by: Philipp Blom

The Lion's Gate: On the Front Lines of the Six Day War by: Steven Pressfield

Private Truths, Public Lies: The Social Consequences of Preference Falsification

By: Timur Kuran

Published: 1995

448 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The concept of preference falsification: the various ways in which people’s private beliefs differ from the opinions they express in public. Additionally, the book discusses how this dichotomy evolves over time and its effect on society.

What's the author's angle?

Kuran is an economist, with a strong interest in freedom of expression. He first came up with the idea of preference falsification in 1987 when it was strongly connected to questions around the persistence of communism.

Who should read this book?

This is a pretty dry book, and it’s probably longer than it needs to be. I suspect that you could get 80% of it by watching a video. (Say this one.)

Specific thoughts: Reason #368 why we can’t have nice things- Transparency

Once upon a time political deals (colloquially known as horse trading) happened in smoke-filled rooms, away from the prying eyes of the public. People felt that these sort of “back room deals” were bad. And indeed such arrangements were often shady and corrupt. The solution to this seemed obvious: transparency.

Transparency does resolve many of these issues, unfortunately like everything else it comes with trade-offs. This is a book about those tradeoffs. And in fact Kuran argues that an increase in transparency at one level leads to a vast decrease at another level—if your outward actions must be absolutely transparent then your true preferences become far less transparent.

As an example of how this plays out we need only look at the recent confirmation hearings being conducted for the Trump nominees. To start with, I have little doubt that if voting were secret, some senators who voted for Trump’s nominees would have opposed them instead. Even if you disagree with this claim (or alternatively think it’s good that Trump has the power to cow senators in this fashion) there’s yet another phenomenon being demonstrated that should be similarly alarming: performative legislators.

If you were following the hearings closely, or really any congressional hearings that took place over the last decade, you might have noticed that they’re very theatrical. Former Senator Ben Sasse remarked on this phenomenon in 2020 when he said:

Most of what happens in committee hearings isn’t oversight, it’s showmanship…senators make speeches that get chopped up, shipped to home-state TV stations, and blasted across social media. They aren’t trying to learn from witnesses, uncover details, or improve legislation. They’re competing for sound bites.

How many times have you seen a clip on social media that urges you to watch as “Congressperson X destroys person Y” (or vice versa)? Should you be foolish enough to click through you won’t see any “destruction” but you will see someone trying very hard to play to the camera.

Speaking of cameras, C-Span started broadcasting sessions of Congress in 1979. I’m sure there are lots of things which have contributed to the performative nature of congress, including increased polarization (though it’s possible I have cause and effect reversed). But the transparency created by these broadcasts has undoubtedly increased public scrutiny, which has directly contributed to the “public lies”, i.e. preference falsification, Kuran refers to.

These days we take secret ballots for granted, but imagine if you had to pick up a colored ballot matching the candidate and then, in front of the entire town, carry it over to the ballot box. In this case, you might cast the ballot least likely to get you yelled at, rather than the ballot representing your true (obviously iconoclastic) opinion. Accounting for some local variation, this is precisely how it used to work. In other words, everything I’ve described is a known problem, at least with respect to average voters. We solved this problem with the secret ballot, which was only implemented with great effort as part of the progressive reforms of the 1890’s. (In the majority of states, that is. South Carolina took until 1950.) We’re now finding out that even a body as august as the United States Senate suffers from the same issue.

As you have probably guessed, this phenomenon does not just appear when votes are being cast. It appears in all sorts of places. Imagine that certain attitudes have been dominant for quite awhile—all right thinking people believe X. Kuran points out that two things are going to happen:

1- There may be a lot of people opposed to the dominant ideology who go years without expressing their true opinion, but once the ideology starts to weaken, huge numbers may emerge “from the woodwork”. I think we’re seeing this with the anti-woke backlash that’s currently happening.

2- Contrariwise, if people express a certain opinion in public for long enough they may eventually come to embrace it. There’s an argument to be made that some portion of the current vociferous defense of wokeism falls into this latter camp.

(I realize I have established an unfalsifiable dichotomy, but also I think it’s accurate despite that.)

As one final point, This book came out long before social media was a thing, which is unfortunate, because social media seems to have taken all of these ideas to extremes Kuran never dreamed of. To a first approximation I would say that social media is nothing but preference falsification…

Enough Already: Time to End the War on Terrorism

By: Scott Horton

Published: 2021

332 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The vast overreach of the War on Terror, the blowback it has caused, and the mistakes that have been made.

What's the author's angle?

Horton is one of the foremost proponents of non-interventionism, which he justifies from a libertarian perspective. Based on those two qualities it should hardly be surprising that he’s opposed to the War on Terror.

Who should read this book?

I’ve read several books in this vein and I’m continually surprised by the number of mistakes the US makes in its dealings with places like Iran, Iraq, Libya, and Afghanistan. As one example, I knew that Saddam had been sent some mixed signals prior to the first Gulf War, but Horton covers a number of such signals which I hadn’t previously come across. As such, if you're looking for reasons why we can’t be trusted to intervene in these areas, even separate from the question of whether it’s a good idea, this book has you covered.

Specific thoughts: Is nuance possible?

Longer ago than I care to remember I did high school policy debate. One of the burdens for the affirmative side in any debate is inherency—they need to show why the problem isn’t being solved already. While the term is more rigorously defined in a debate tournament, it’s something that comes up all the time when discussing problems and their solutions. “Why is there no affordable housing? Why are taxes so high?” And generally the answer is “The other side did X” or “The other side prevents us from doing Y”.

That sort of framing doesn’t work here. Horton is just as scathing in his criticisms of Obama as he is in his criticisms of Bush. And the accusations he’s leveling are not minor, Horton describes colossal mistakes. Mistakes that make you wonder how people could be so monumentally bad at their jobs, so clueless in their understanding, and so heedless of the consequences of their decisions.

Given the magnitude of the mistakes, the question of “Why?” looms very large. If distortions in procurement mean that the military pays a little more for a widget than it should, we should figure out what happened, but it might not be at the top of our priority list. On the other hand if imperial hubris leads to the military killing hundreds of thousands of people then figuring out what happened is enormously important. But despite how important this question is, Horton largely leaves it unanswered.

He does a lot of vague gesturing in the direction of “the powerful”. But even if Horton had actionable advice to dispense, making it about the powerful presents a different problem. If those in power always want to do X, and only those without power are opposed to X, well then X is likely to continue to happen.

To return to inherency, I can accept that the problem isn’t being solved, but the book left me mystified as to why? How is it that every administration, regardless of their political affiliation, continues to perform so disastrously? How is it that everyone involved is universally incompetent? Why are both parties so united on maintaining damaging and destructive policies in all of these countries? Particularly when they’re disunited on so many other fronts. (I say this with the caveat that we’re still early days in the Trump presidency, and there is some possibility he’ll be different.)

I can imagine a few possibilities:

The war on terror (or 9/11) made everyone crazy. When you combine the arrogance of being a hyperpower, with the expectation of safety that comes from unprecedented security against foreign attack, you end up with a giant bubble of perceived invincibility. 9/11 popped that. In the aftermath there was no measure too extreme, no plan too crazy. The War on Terror is the result of that, and having painted ourselves into this corner we find it very difficult to extract ourselves.

On the other hand, perhaps there’s something structurally that demands it. Many people, myself included, are proponents of the idea that American Hegemony has brought unprecedented stability and material abundance. Perhaps something akin to the War on Terror is necessary to maintain that hegemony. The world is a prison yard full of tattooed gangs, and it’s necessary to continually smack down the most aggressive of these gangs if you want to retain your spot as top dog.

Speaking of aggressive gangs, perhaps the mess only comes from intervening in majority Muslim countries? We have troops in South Korea and Europe. We have somewhat ambiguous commitments to Taiwan. Despite being a proponent of non-intervention, Horton doesn’t criticize our interventionist postures in those places. (He only mentions Taiwan once, and South Korea not at all.) Perhaps we just continually underestimate the unique difficulties of intervening in majority Muslim countries.

Another possibility is that Horton isn’t telling us the whole story. This is almost certainly true because all accounts are told from a limited standpoint, but there’s always a possibility it goes even deeper. I didn’t spot any obvious mistakes like I did in some other books, but given the issue of inherency, I strongly suspect that Horton is simplifying a situation that is, in reality, horribly complex.

Finally, there’s the possibility that it’s all Israel’s fault. I say this not as an anti-semetic conspiracy, but more as an observation about the weird place Israel occupies in the whole dynamic. To return to the prison yard analogy. Perhaps there’s one member of our broader coalition (okay, our gang) that just happens to always sit at the table claimed by the rival gang. Perhaps he has good reasons for doing so. But it ends up being a source of perpetual conflict that might not exist otherwise.

To return to my initial point, Horton doesn’t really go into the “why” of things, which is the big disappointment of the book. To the extent that he comes down on the side of any of my suggested possibilities he’s probably closest to the “it’s all Israel’s fault”. Which is not to say that he’s anti-semetic, merely that it is true that Israel's presence distorts things in a lot of ways.

Taking this, along with this critique of the “powerful”, perhaps we can charitably construct a reason for why these disasters might keep happening, but this construct doesn’t give us any insight into how to solve the problem. Certainly we should stop doing dumb stuff in the greater Middle East, but that’s been a goal for a long time now, and, regardless of who’s in power we have yet to succeed. Beyond that no one of any influence, including Horton, is suggesting the elimination of Israel. All of which is to say that while I’m sympathetic to the problems Horton raises, I’m pretty sure there’s some utopian second path that we’ve just been ignoring all these years.

The problems Horton points out have their roots in things that happened long before I was born, and I’m confident these problems will continue long after I’m dead.

The Gulag Archipelago [Volume 1]: An Experiment in Literary Investigation (1918-1956)

Published: 1973

660 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The first volume in the definitive expose of the vast Soviet prison system—the gulags. With a particular focus on the atrocities, the hypocrisies, and most of all the insanities associated with them.

What's the author's angle?

Solzhenitsyn spent a decade imprisoned in the gulags, so he is definitely not a disinterested observer, but his perspective is all the more valuable because he was so deeply ensconced in the various injustices.

Who should read this book?

Everyone should read this book, though I suspect a lot of people will not want to.

Specific thoughts: Laughing because it hurts too much to do anything else.

In the book Stranger in a Strange Land, Valentine Michael Smith returns to Earth after being raised from birth exclusively by Martians. As such,when he returns to Earth his understanding of humanity is very limited. Among the many things he doesn’t understand is why humans laugh. Finally, about three-fourths of the way through the novel he comes to the conclusion that we “laugh because it hurts so much ... because it's the only thing that'll make it stop hurting”.

If you’re unfamiliar with Stranger in a Strange Land then perhaps you’ve seen The Death of Stalin, a 2017 black comedy about the power struggle among the Soviet Politburo in the immediate aftermath of Stalin’s death. I would recommend both of them. I bring them up because I’m hoping they’ll provide cover for a controversial point I want to make: I found the Gulag Archipelago to be funny. Darkly humorous, like Death of Stalin. Perhaps the darkest humor there is. Humorous because the insanity of Stalin’s Russia hurts so much that a grim chuckle is the only thing that might make it stop hurting.

Consider this list of how people were arrested:

One has to give the Organs their due: in an age when public speeches, the plays in our theaters, and women's fashions all seem to have come off assembly lines, arrests can be of the most varied kind. They take you aside in a factory corridor after you have had your pass checked—and you're arrested. They take you from a military hospital with a temperature of 102, as they did with Ans Bernshtein, and the doctor will not raise a peep about your arrest—just let him try! They'll take you right off the operating table—as they took N. M. Vorobyev, a school inspector, in 1936, in the middle of an operation for stomach ulcer—and drag you off to a cell, as they did him, half-alive and all bloody (as Karpunich recollects). Or, like Nadya Levitskaya, you try to get information about your mother's sentence, and they give it to you, but it turns out to be a confrontation—and your own arrest! In the Gastronome—the fancy food store—you are invited to the special-order department and arrested there. You are arrested by a religious pilgrim whom you have put up for the night "for the sake of Christ." You are arrested by a meterman who has come to read your electric meter. You are arrested by a bicyclist who has run into you on the street, by a railway conductor, a taxi driver, a savings bank teller, the manager of a movie theater. Any one of them can arrest you, and you notice the concealed maroon-colored identification card only when it is too late.

The system Solzhenitsyn describes is so insane, so arbitrary, and so comprehensive that you start to imagine that it has to be a farce of some sort. It provides one of those occasions where the situations wouldn’t work as fiction because you’d accuse the author of lazily tossing out a world that doesn’t make sense. It can only be the truth because sometimes reality is just that insane, and I’m not sure madness has ever been so omnipresent as it was in Stalin’s Russia.

The book, and the situations it describes, is beyond grim, beyond horrible. It arrives at a place of the darkest humor. May we be spared from ever experiencing something similarly humorous.

Climate Shock: The Economic Consequences of a Hotter Planet

By: Gernot Wagner & Martin L. Weitzman

Published: 2015

264 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The economics of preventing global warming, which seems to mostly amount to pricing carbon and preventing geo-engineering.

What's the author's angle?

The two authors definitely fall on the more extreme end of the spectrum in their predictions of how catastrophic global warming will end up being.

Who should read this book?

This was recommended to me as something of a steelmanning for an extreme view of global warming. If you already hold that view, I’m not sure you’ll find that much that is new. As someone who doesn’t place global warming at the top tier of x-risks, I found their tone to be even and their recommendations to be straightforward.

Specific thoughts: What are we supposed to do here?

The phrase that kept popping up in my head as I read this book was “gas prices”. I’m not sure that high gas prices propelled Trump to victory (though “Inflation/prices” was ranked as the #1 issue by voters) but it did seem to be one of the big issues. Now imagine that instead of just being unlucky enough to be in power during rising prices if Biden and Harris had actually implemented a carbon tax of $40/gallon (the price this book recommends). Such a tax would directly and indisputably increase gas prices by around $0.36/gallon on top of any increases which happened for other reasons. Obviously even without such a tax Harris didn’t win, and I don’t think I’m being particularly controversial to say that had she implemented such a tax, she would have lost by even more.

The question which then confronts us is: Could anyone successfully implement such a tax? Pass a law (or issue an executive order). And do it in such a way that it sticks? Based on the evidence of the most recent election, I would have to say not anytime soon. Perhaps I’m wrong about this, Yoram Bauman, the guy who recommended the book to me, is hoping to implement a carbon tax in Utah and if you could pull it off in a deep red state like Utah, there’s some chance you could do it nationwide.

As anyone who’s been reading my stuff for awhile knows, I’m a big proponent of nuclear power. This book is another book about global warming which makes the strange decision to never mention nuclear power, not once. As in, a search for the word “nuclear” turns up one glancing reference to nuclear power in the end notes (but lots of references to nuclear weapons).

I’m not sure what to make of this. I mean I understand that a carbon tax will be a subsidy for nuclear power, so they are connected, but that just deepens the mystery. Given the connection, why wouldn’t they mention this benefit?

I’m almost at the point of assuming there’s some rule I’m unaware of that prevents people who write about global warming from mentioning nuclear power. I’m having a hard time thinking of another reason why it’s so conspicuously absent from a book like this. Beyond this mystification I think nuclear power creates an interesting comparison. Just like carbon taxes, nuclear power is unpopular, particularly nuclear waste.

For the moment, let’s assume that nuclear power would be just as efficacious as carbon taxes at lowering the amount of carbon that gets emitted. (I understand that’s probably not the case, but stick with me for a minute.) Is it easier to get people to accept higher gas taxes or easier to get them to live with nuclear waste?

My sense would be that the latter is easier. Or to put it another way, one can imagine a carbon tax tanking someone’s election all by itself. One can’t imagine that nuclear power all by its lonesome would be similarly fatal to someone’s chances. I could be wrong. We haven’t seen politicians rushing to embrace either policy, so it’s hard to say.

There’s obviously much more to the book. I appreciated the discussion of “fat tails”—extreme outcomes have a higher probability than “normally” expected. And the idea that geoengineering may be a free driver problem, instead of a free rider problem—something that’s so easy and cheap that it would be hard to keep people from doing it.

Finally, I appreciate their discussion of the broader realm of x-risks as they compare to global warming. I think they understate the danger of the other x-risks, and overstate the danger of global warming, but given the subject of the book, you’d expect nothing less.

The Vertigo Years: Europe 1900-1914

By: Philipp Blom

Published: 2008

488 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The dramatically eventful years which preceded World War I. Years which are overshadowed by later events but critical to the understanding of what happened.

Who should read this book?

If you have a special fondness for World War I including what preceded it, or modern European history in general you’ll like this book.

Specific thoughts: It was remarkable how much was happening during this time period.

I can’t do justice to all of the changes happening during this period, but just to give you a sense of things here’s short list of dramatic changes which all occurred during this 14 year period (so imagine this all happened to us between 2010 and now):

Radio: Not really invented until 1895. First transatlantic broadcast in 1901. By 1914, the first radio stations had emerged.

Cinema: In 1900 film was short and mostly just covered a single scene. Around 1905-1910 they started to reach around 10-15 minutes and nickelodeons were opening up all over the US and Europe. Films kept getting longer and longer, culminating in Birth of a Nation which was released in 1915.

Cars: In 1900 cars were almost entirely hand-built toys of the wealthy. In 1908 the Model T was introduced, and by 1914 it only cost $500 and only took 90 minutes to build.

Aviation: The Wright Brothers first flight was in 1903. By 1914 aircraft could reach speeds of 100+ mph and altitudes of over 20,000 feet.

Beyond the rapid advance of technology there were large changes happening at the civilizational level.

Russia was roiled by unrest, particularly after losing the Russo-Japanese War.

The naval arms race between the UK and Germany kicked off with the launching of the HMS Dreadnought in 1906.

The Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 foreshadowed World War I. And in general nationalism was ascendent. Into this mix you also had socialism and anarchism, which were also major ideological forces.

As unsettled as things were at the civilizational level, they might have been even more unsettled at the level of the individual. As Virginia Woolf said, “in or around December, 1910, human character changed”. What was the driver of these changes?

Freud published On the Interpretation of Dreams in 1900, which marked the formal beginnings of psychoanalysis. It wasn’t long before everyone was talking about repressed sexual desires.

Modernism in art (Picasso) and writing (Kafka and Joyce) were just starting to take off.

The women’s suffrage movement was in full swing, along with many other liberatory struggles against traditional norms.

Also as one of those episodes/movements that people would like to forget. Eugenics also started gaining broad attention during this period as well.

I’ve really only scratched the surface of this remarkably tumultuous period. A period which in many ways reminds me of our own…

The Lion's Gate: On the Front Lines of the Six Day War

Published: 2014

448 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The Six-Day War told from the point of view of the Israelis who participated in it.

What's the author's angle?

Pressfield is Jewish (technically but not culturally) and he’s definitely committed to valorizing the Israeli side of the conflict. (Which is not a criticism, what they did was amazing.)

Who should read this book?

Anyone who’s interested in war at all, particularly the human side, should read this book.

Specific thoughts: It’s easy to forget that at one point the Isrealis were the underdogs, by a lot.

It can be difficult to poke one’s head out from the current mess in the Middle East in order to consider the broader sweep of history. Of course going back to 1967 and the Six Day War, represents only a tiny hop when you’re talking about an area of millennial-old grudges. Nevertheless reading this book was felt like a peek into a far different world.

I mean everyone knows Israel’s existence was tenuous, but this really brings home how tenuous. Everyone knows that the US and Israel were not always as tightly allied as they are now, but until reading this book I didn’t realize how minimal their help had been in advance of this war. To the extent that the US provided any help it was mostly WWII surplus.

On the other side of the equation, everyone knows that the Arab world is united in their opposition to Israel, but everything was much more cohesive in 1967. Not only that, the military advantage possessed by the Arabs (on paper at least) was overwhelming. We’re not used to thinking of Israel as the scrappy low-tech underdogs, but in 1967 that was definitely the case.

This book is a great exploration of being backed into a corner—of a people acting at critical moments while in great danger. I’m not sure I’d recommend it as a national strategy, but the constant danger—the memory of the holocaust was still very fresh—had honed their skills and their focus to a razor’s edge. The Israelis had to execute all of their plans to perfection if they were going to survive. Having read about the skill with which they executed their incredibly complicated plan to take out the Egyptian Air Force, the pager attack on Hezbollah seems like something everyone should have expected.

Perhaps the biggest strength of the book is its description of the experiences of the actual soldiers, particularly the way in which Pressfield makes them all POV characters. For conveying the viscerality of war it’s the equal of Band of Brothers. It was gripping from the first page to the last.

Since I started breaking up my book reviews by type I’ve gotten out of the habit of doing brief personal updates. If you would like those to return let me know. But I do have time for one personal update. I, personally, decided to turn on paid subscriptions. Consider getting one (or not the difference is slight.)