Job Automation, or Can You Recognize a Singularity When You're In It?

If you prefer to listen rather than read, this blog is available as a podcast here. Or if you want to listen to just this post:

Over the last few months, it seems that regardless of the topic I’m writing on, that they all have some connection, however tenuous, to job automation. In fact, just last week I adapted the apocryphal Trotsky quote to declare that, “You may not be interested in job automation, but job automation is interested in you.” On reflection I may have misstated things, because actually everyone is interested in job automation they just don’t know it. Do you care about inequality? Then you’re interested in job automation. Do you worry about the opiate epidemic? Then you’re interested in job automation. Do you desire to prevent suicide by making people feel like they’re needed? Then you’re interested in job automation. Do you use money? Does that money come from a job? Then you’re interested in job automation. Specifically in whether your job will be automated, because if it is, you won’t have it anymore.

As for myself, I’m not merely interested in job automation, I’m worried about it, and in this I am not alone. It doesn’t take much looking to find articles describing the decimation of every job from truck driver to attorneys or even articles which claim that no job is safe. But not everyone shares these concerns, and whether they do depends a lot on how they view something called the Luddite Fallacy. You’ve probably heard of the Luddites, those English textile workers who smashed weaving machines between 1811 and 1816, and if you have, you can probably guess what the Luddite Fallacy is. But in short, Luddites believed that technology destroyed jobs (actually that’s not quite what they believed, but it doesn’t matter). Many people believe that this is a fallacy, that technology doesn’t destroy jobs. It may get rid of old jobs, but it opens up new and presumably better jobs.

Farmers are the biggest example of this fallacy. In 1790, they composed 90% of the US labor force, but currently it’s only 2%. Where did the 98% of people who used to be farmers end up? They’re not all unemployed, that’s for sure. Which means that the technology which put nearly all of the farmers out of work, did not actually result in any long term job loss. And the jobs which have replaced farming are all probably better. This is the heart of things for people who subscribe to the Luddite Fallacy, the idea that the vast majority of jobs which currently exist were created when labor and capital were freed up when technology eliminated old jobs, and farmers aren’t the only example of this.

More or less, this is the argument in favor of the fallacy; in support of the idea that you don’t have to worry about technology putting people out of work. And people who think the Luddite Fallacy still applies aren’t worried about job automation. Because they have faith that new jobs will emerge. And just as in the past when farmers became clerks and clerks became accountants, as accounting is automated, accountants will become programmers, and when at last computers can program themselves, programmers will become musicians or artists or writers of obscure, vaguely LDS, apocalyptic blogs.

The Luddite Fallacy is a strong argument, backed up by lots of historical evidence, the only problem is, just because that’s how it worked in the past doesn’t mean that there’s some law saying it has to continue to work that way. And I think it’s becoming increasingly apparent that it won’t continue to work that way.

Recently the Economist had an article on this very subject and they brought up the historical example of horses being replaced by automobiles. As they themselves point out, the analogy can be taken too far (a point they mention right after they discuss the number of horses who left the workforce by heading to the glue factory.) But the example nevertheless holds some valuable lessons.

The first lesson we can learn from the history of the horse’s replacement is that horses were indispensable for thousands of years until suddenly they weren’t. By this, I mean to say that the transition was very rapid (it took about 50 years) and the full magnitude was only obvious in retrospect. What does this mean for job automation? To start with, if it’s going to happen, than 50 years is probably the longest it will take. (Since technology moves a lot faster these days.) Additionally, it’s very likely that the process has already begun and we’ll only be able to definitely identify the starting point in retrospect. Though, just looking at self-driving cars I can remember the first DARPA Grand Challenge in 2004 when not a single car finished the course, and now look at how far we’ve come in just 13 years.

The second lesson we can learn concerns the economics of the situation. Normally speaking, the Luddite Fallacy kicks in because technology frees up workers and money which can be put to other uses. This is exactly what happened with horses. The advent of tractors and automobiles freed up capital and it freed up a lot of horses. Anyone who wanted a horse had access to plenty of cheap horses. And yet that didn’t help. As the article describes it:

The market worked to ease the transition. As demand for traditional horse-work fell, so did horse prices, by about 80% between 1910 and 1950. This drop slowed the pace of mechanisation in agriculture, but only by a little. Even at lower costs, too few new niches appeared to absorb the workless ungulates. Lower prices eventually made it uneconomical for many owners to keep them. Horses, so to speak, left the labour force, in some cases through sale to meat or glue factories. As the numbers of working horses and mules in America fell from about 21m in 1918 to only 3m or so in 1960, the decline was mirrored in the overall horse population.

In other words there will certainly be a time when robots will be able to do certain jobs, but humans will still be cheaper and more plentiful, and as with horses that will slow automation down, “but only by a little.” And, yes, as I already mentioned the analogy can be taken too far, I am not suggesting that surplus humans will suffer a fate similar to surplus ungulates (gotta love that word.) But with inequality a big problem which is getting bigger we obviously can’t afford even a 10% reduction in real wages to say nothing of an 80% reduction. And that’s while the transition is still in progress!

For most people when they think about this problem they are mostly concerned with unemployment or more specifically how people will pay the bills or even feed themselves if they have no job and no way to make money. Job automation has the potential to create massive unemployment, and some will argue that this process has already started or that in any event the true unemployment level is much higher than the official figure because many people have stopped looking for work. Also while the official figures are near levels not seen since the dotcom boom they mask growing inequality, significant underemployment, an explosion in homelessness and increased localized poverty.

Thus far, whatever the true rate of unemployment, and whatever weight we want to give to the other factors I mentioned, only a small fraction of our current problems come from robots stealing people’s jobs. A significant part of it comes from manufacturing jobs which have moved to another country. (In the article they estimate that trade with China has cost the US 2 million jobs.) In theory, these jobs have been replaced by other, better jobs in a process similar to the Luddite fallacy, but it’s becoming increasingly obvious, both because of growing inequality and underemployment, that when it comes to trade and technology that the jobs aren’t necessarily better. Even people who are very much in favor of both free trade and technology will admit that manufacturing jobs have largely been replaced with jobs in the service sector. For the unskilled worker, not only do these jobs not pay as much as manufacturing jobs, they also appear to not be as fulfilling as manufacturing jobs.

We may see this very same thing with job automation, only worse. So far the jobs I’ve mentioned specifically have been attorney, accountant and truck driver. The first two are high paying white collar jobs, and the third is one of the most common jobs in the entire country. So we’re not seeing a situation where job automation applies to just a few specialized niches, or where they start with the lowest paying jobs and move up. In fact it would appear to be the exact opposite. You know what robots are so far terrible at? Folding towels. I assume they are also pretty bad at making beds and cleaning bathrooms, particularly if they have to do all three of those things. In other words there might still be plenty of jobs in housekeeping for the foreseeable future, but obviously this is not the future people had in mind.

As I’ve said I’m not the only person who’s worried about this. A search on the internet uncovers all manner of panic about the coming apocalypse of job automation, but where I hope to be different is by pointing out that job automation is not something that may happen in the future, and which may be bad. It’s something that’s happening right now, and it’s definitely bad. This is not to say that I’m the first person to say job automation is already happening, nor am I the first person to say that it’s bad. Where I do hope to be different is by pointing out some ways in which it’s bad that aren’t generally considered, tying it into larger societal trends, and most of all pointing out how job automation is a singularity, but we don’t recognize it as such because we’re in the middle of it. For those who may need a reminder I’m using the term singularity as shorthand for a massive technologically driven change in society, which creates a world completely different from the world which came before.

The vast majority of people don’t look at job automation as a singularity, they view it as a threat to their employment, and worry that if they don’t have a job they won’t have the money to eat and pay the bills and they’ll end up part of the swelling population of homeless people I mentioned earlier. But if the only problem is the lack of money, what if we fixed that problem? What if everyone had enough money even if they weren’t working? Many people see the irresistible tide of job automation on the horizon, and their solution is something called a guaranteed basic income. This is an amount of money everyone gets regardless of need and regardless of whether they’re working. The theory is, that if everyone were guaranteed enough money to live on, that we could face our jobless future and our coming robot overlords without fear.

Currently this idea has a lot of problems. For one even if you took all the money the federal government spends on everything and gave it to each individual you’d still only end up with $11,000/per person/per year. Which is better than nothing, and probably (though just barely) enough to live on, particularly if you had a group of people pooling their money, like a family. But it’s still pretty small, and you only get this amount if you stop all other spending, meaning no defense, no national parks, no FTC, no FDA, no federal research, etc. More commonly people propose taking just the money that’s being currently spent on entitlement programs and dividing that up among just the adults (not everyone.) That still gets you to around $11,000 per adult, which is the same inadequate amount I just mentioned but with an additional penalty for having children, which may or may not be a problem.

As you can imagine there are some objections to this plan. If you think the government already spends too much money then this program is unlikely to appeal to you, though it does have some surprising libertarian backers. But there are definitely people who are worried that this is just thinly veiled communism and it will lead to a nation of welfare receipts with no incentive to do anything. That while this might make the jobless future slightly less unfair that in the end it will just accelerate the decline.

On the other hand there are the futurists who imagine that a guaranteed basic income is the first step towards a post-scarcity future where everyone can have whatever they want. (Think Star Trek.) Not only is the income part important, but, as you might imagine job automation, plays a big role in visions of a post scarcity future. The whole reason people worry about robots and AI stealing jobs is that they will eventually be cheaper than humans. And as technology improves what starts out being a little bit cheaper eventually becomes enormously cheaper. This is where the idea, some would even say the inevitability of the post scarcity future comes from. These individuals at least recognize we may be heading for a singularity, they just think that it’s in the future and it’s going to be awesome, while I think it’s here already and it’s going to be depressing.

All of this is to say that there are lots of ways to imagine job automation going really well or really poorly in the future but that’s the key word, the “future”. In all such cases people imagine an endpoint. Either a world full of happy people with no responsibilities other than enjoying themselves or a world full of extraneous people who’ve been made obsolete by job automation. But of course neither of these two futures is going to happen in an instant, even though they’re both singularities of a sort. But that’s the problem, singularities are difficult to detect when you’re in them. I often talk about the internet being a soft singularity and yet, as Louis C.K. points out in his famous bit about airplane wi-fi we quickly forget how amazing the internet is. In a similar fashion, people can imagine that job automation will be a singularity, but they can’t imagine that it already is a singularity, that we are in the middle of it, or that it might be part of a larger singularity.

But I can hear you complaining that while I have repeatedly declared that it’s a singularity, I haven’t given any reasons for that assertion, and that’s a fair point. In short, it all ties back into a previous post of mine. As I said at the beginning, it has seemed recently that no matter what I’m writing about, it ties back into job automation. The post where this connection was the most subtle and yet at the same time the most frightening is while I was writing about the book Tribe by Sebastion Junger.

Junger spent most of the book talking about how modern life has robbed individuals of a strong community and the opportunity to struggle for something important. He mostly focused on war because of his background as a war correspondent with time in Sarajevo, but as I was reading the book it was obvious that all the points he was making could be applied equally well to those people without a job. And this is why it’s a singularity, and this is also what most people are missing. The basic guaranteed income people along with everyone else who wants to throw money at the problem, assume that if they give everyone enough to live on that it won’t matter if people don’t have jobs. The post scarcity people take this a step further and assume that if people have all the things money can buy then they won’t care about anything else, but I am positive that both groups vastly underestimate human complexity. They also underestimate the magnitude of the change, as Junger demonstrated there’s a lot more wrong with the world than just job automation, but it fits into the same pattern.

Everyone looks around and assumes that what they see is normal. The modern world is not normal, not even close. If you were to take the average human experience over the whole of history then the experience we’re having is 20 standard deviations from normal. This is not to say that it’s not better. I’m sure in most ways that it is, but when you’re living through things, it’s difficult to realize that what we’re experiencing is multiple singularities all overlapping and all ongoing. The singularity of industrialization, of global trade, of fossil fuel extraction, of the internet, and finally, underlying them all, what it means to be human. As it turns out job automation is just a small part of this last singularity. What do humans do? For most of human history humans hunted and gathered, then for ten thousand more years up until 1790 most humans farmed. And then for a short period of time most humans worked in factories, but the key thing is that humans worked!!! And if that work goes away, if there is nothing left for the vast majority of humans to do, what does that look like? That’s the singularity I’m talking about, that’s the singularity we’re in the middle of.

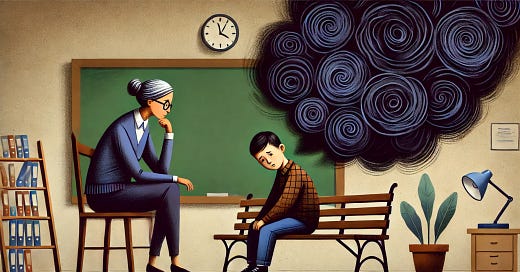

As I pointed out in my previous post, as warfare has changed, the rates of suicide and PTSD skyrocketed. Obviously having a job is not a struggle on the same level as going to war, but it is similar. As it goes away are we going to see similar depression, similar despair and similar increases in suicide? I think the evidence that we’re already in the middle of this crisis is all around us. There are a lot of disaffected people who were formerly useful members of society who have stopped looking for work and who have decided that a life addicted to opioids is the best thing they can do with their time. This directly leads to the recent surge in Deaths of Despair I also talked about in that post, which we’re seeing on top of the skyrocketing rates of suicide and PTSD. The vast majority of these deaths occur among people who no longer feel useful, in part for the reasons outlined by Junger and in part because they either no longer have a job or no long feel their job is important.

In closing, much of what I write is very long term, though based on some of the feedback I get that’s not always clear. To be clear I do not think the world will end tomorrow, or even soon, or even necessarily that it will ever end. I hope more to push for people to be aware that the future is unpredictable and it’s best to be prepared for anything. And also, as we have seen with job automation and the corresponding increase in despair, in some areas the future is already happening.

I am reliably informed that the job of donating to this blog has not been automated, you still have to do it manually.