Challenging Children

If you prefer to listen rather than read, this blog is available as a podcast here. Or if you want to listen to just this post:

I.

The story of Adam and his father in my last essay, The Ineffability of Conservatism, generated a lot of pushback. The negative reactions mostly came from people who were never religious or who had left religion in a fashion similar to Adam. None had taken that journey when they were quite so young, but some wished that they had. And while I think religion had an important role to play in the story, a role I’ll be returning to before the end, I also think that its inclusion may have obscured the fundamental message. (Though using the word “ineffability” in the title probably didn’t help.)

Actually, I take that back. The fundamental problem is still somewhat opaque to me, which means that the fundamental message must necessarily be as well. But, the presence of religion made some points less clear than they could have been. So I decided to take another stab at the topic from a different direction.

For those unfamiliar with the previous essay, I told the story of Adam, a young man who had decided he no longer believed in the religion of his family and local community. In an attempt to influence him towards staying, the bishop/pastor had arranged for Adam’s father to teach his Sunday School class. Adam, upon seeing that his father was going to teach, very publicly left, despite his father’s entreaties to stay. Much of the post was a reflection on how it would have never even occurred to people of my generation to do such a thing.

As you can see the story had a very heavy religious angle. It was clearly about young people leaving the faith of their fathers. Which is happening a lot. But it’s also a story about raising children, and parenting. So I decided to write a follow up post where I approach it from that side of things. I think doing so might make certain points easier to get to.

Perhaps there’s something in the water because the minute I made that decision I came across some other people making points similar to the ones I would like to make. Let’s start with Freddie deBoer. Freddie opened the new year with a post titled, Resilience, Another Thing We Can't Talk About. As you may or may not know, Freddie is no fan of religion. (His second post of the year bemoaned the fact that Richard Dawkins style atheism/skepticism has fallen out of fashion.) But, despite our diametrically opposed religious views, his discussion of resilience is definitely heading in the same direction I plan on going:

If I know one thing is true about every single person reading this, it’s that at some point in 2023, they will suffer. Teaching people how to suffer, how to respond to suffering and survive suffering and grow from suffering, is one of the most essential tasks of any community. Because suffering is inevitable. And I do think that we have lost sight of this essential element of growing up in contemporary society, as armies of helicopter parents pull the leash on their kids tighter and tighter and as harm reduction has eaten every other element of left politics.

Suffering is a big topic, and while Freddie seems mostly focused on involuntary suffering, people also choose to suffer. In my extended family, we frame this latter form of suffering as “doing hard things”. And it’s my contention (and perhaps Freddie’s as well) that teaching children how to do hard things is one of the central tasks of a parent. Your children are definitely going to be confronted with hard things once they’re adults, and if they haven’t mastered that skill or at least practiced it, they’re likely going to fail — maybe catastrophically.

Even if someone agrees that it’s useful to have children do hard things, they may balk at putting all suffering in the same bucket. There is an argument to be made that the challenge of studying hard enough to get a scholarship is a completely different thing than being bullied at school, and that the challenge of attending church when you would rather not, is yet a third sort of challenge. Part of the purpose of this post will be to demonstrate that there’s less difference than you might think, and I will further argue that, even if there is, the skills developed to deal with voluntary suffering can help with involuntary suffering as well.

Unfortunately, as Freddie points out, a large part of society does not even agree with the need for voluntary suffering. Freddie asserts that everyone will end up suffering at some point during the next year, and this is true, but suffering isn’t guaranteed the way it once was. And while the effect has been gradual, this has led some to decide that suffering can and largely should be eliminated — both the involuntary and the voluntary. Often these people are parents. Freddie calls them “helicopter parents”. I prefer the more recent term “snowplow parents”, parents who clear the path in front of the child, pushing aside all obstacles. Obviously some examples of such parents are more extreme than others. But it’s gotten to the point where lots of these attitudes have spread to society at large and become the default. The question is how did this happen? And can anything be done?

II.

One of the major themes in my previous post was the difference between the conditions teenagers experience now and the conditions I experienced when I was a teenager. These differences are numerous and run the gamut from really large things, like the internet, to small things, like the proliferation of memes. We’ll examine some of the bigger things in a moment, but I would also argue that simply making a list doesn’t do justice to the profound difference between now and 40 years ago. First, we’re almost certainly overlooking some of the things which have changed, because they’re either too small to measure or no one has bothered to measure them. But more importantly, I think that we’ve yet to fully grasp the way changes combine and feed off one another.

Out of all this, clearly one difference is a broad reduction in the amount of material suffering: The infant mortality rate in the US has nearly halved just since 1990. The child poverty rate has been reduced from 20% to 5% since 1983. And, while these numbers are harder to quantify, childhood injuries appear to also be declining. The obvious progress we’ve made has encouraged parents, who were already predisposed to do everything they can for their kids, to look for ways to eliminate all the suffering which still remains. Given our previous successes, it’s worth asking, “What's the harm in that?” Unfortunately the answer might be “substantial”.

Obviously I’m not the first person to make this argument, nor will I be the last, but it’s worth reviewing the arguments in light of the different ways suffering can manifest. Probably the best known book to tackle this subject is The Coddling of the American Mind by Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt. We don’t have the space to go into everything but a few years ago I did spend a couple of posts talking about it. The Coddling of the American Mind puts forth the idea that there are three great untruths which have spread far and wide through the education system, and society as a whole. As part of our current discussion we’re just going to look at the first one:

The Untruth of Fragility: What doesn’t kill you makes you weaker.

Freddie calls this untruth the quest for “harm reduction [which] has eaten every other element of left politics.” Lukianoff and Haidt argue that it really kicked in on college campuses starting around 2013, so children born starting in 1995. They mention that this maps to the cohort Jean Twenge labeled as iGen, in her book of the same name. On the opposite side of things from these college kids there is, of course, Nietzsche, from whom the authors adapted their label. And, as you might imagine, since they call it an untruth, Lukianoff and Haidt, who make the case that college students (and humans in general) are antifragile — exposure to stress and suffering make them stronger, up to a point.

That last bit “up to a point” is where most of the fighting takes place. My guess is that most people reading this, and indeed most people, period, agree that children need some challenges. (If you don’t think children need to be strong and resilient this post is not for you.) The fight is over where to draw the line. Which sorts of stress and suffering should be put in the beneficial bucket and which sorts of stress and suffering should be put in the garbage? Obviously involuntary suffering, by definition, can’t be disposed of. So, taken together, we’ve identified three buckets:

Challenges you can’t avoid.

Challenges you can avoid but choose not to.

Challenges you can avoid and choose to.

Some people would argue that the greater ability to move things from bucket one to bucket three is the whole point of progress. And while humans have been moving things from one to three since at least the dawn of agriculture, lately we’ve gotten a lot better at it, to the point where some would argue that we’re within shouting distance of emptying bucket one. (Which might be a serviceable definition of transhumanism.)

While this movement from one to three is interesting, the subject of this post mostly hinges on whether, if the challenge is in fact voluntary, we should ever place it in bucket two rather than bucket three. And beyond that, under what circumstances the parent should be empowered to put a challenge in bucket two when the child really wants it to be in bucket three.

As I mentioned, our ability to move things out of the first bucket has been increasing for a long time, but Lukianoff and Haidt are arguing that the desirability of moving things from backet two to three has dramatically increased in just the last ten years. There are certainly lots of reasons why this has happened, and getting into the actual causes would take us too far afield, but what Lukianoff and Haidt, and for that matter deBoer are arguing is that it’s spread far and wide enough to have become a societal expectation. Particularly when you’re making the choice between bucket two and three for someone else, i.e. your kids.

To put it in more blunt terms: it would be insane to argue that we should be maximizing the suffering of children, but on the other hand it seems equally obvious that they need some amount of resilience, some ability to do hard things. So where do we draw the line? If we need to put something into bucket two, what criteria should we use? And perhaps more importantly what criteria should be culturally acceptable? Because if there’s a disconnect between the criteria we “should” be using and the criteria society finds acceptable then society is eventually going to win.

III.

At this point we’re still dealing with fairly crude divisions. If we’re going to get to the heart of the issue we’re going to have to start slicing things more finely, if at all possible. We need to start differentiating between various kinds of stress and suffering, and specific sorts of challenges.

To start with, homework and other associated educational activities seem to be pretty mainstream, bucket two items. Beyond that some people feel that forcing kids to take music lessons is entirely appropriate. Still other parents are going to very strongly encourage their kids to play sports. By looking at activities like these we should be able to extract some attributes that allow us to differentiate between challenges that should be in bucket two versus those that should be in bucket three. Though, before we do so, it’s sobering to note that even within these broadly unobjectionable categories the expectations we place on kids have been eroding over the last few decades. A trend that was only accelerated by the pandemic.

As a final thought, It’s probably worth mentioning a subcategory of challenges within the preceding examples that involve having children confront their fears, particularly if those fears are irrational, like performing in front of people. Thus the phenomenon music recitals and actual competition with sports.

We’ve covered, however briefly, forcing or at least strongly encouraging kids to do certain things. What about the flip side of that, restricting kids from doing things? The challenge we’re giving them here is not to do hard things, but to avoid pleasurable things. (Though such avoidance can certainly end up being a hard thing to pull off.) Here again we notice a cultural and societal shift. Certain restrictions against pleasurable things are as old as time itself, but recently both the number and the availability of pleasurable things has increased. Which means we have to implement broader restrictions, starting much younger than in the past. The expanded scope of this task has made the problem much larger than it was in the past.

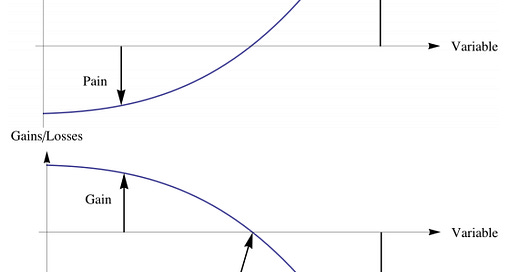

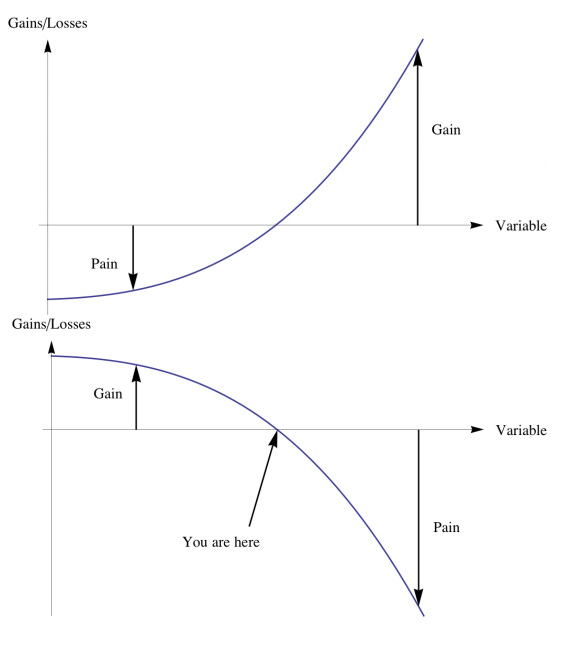

We’ve already mentioned antifragility in this space, and I think most of the things we’ve mentioned can be placed in that framework. What does this framework look like? Well as it turns out you can graph it:

Antifragility comes from paying small fixed costs which cumulatively increase the chances of massive returns. (For the purposes of our discussion the variable is time.) So if a teenager pays the cost of being a diligent student they increase their chances of getting into a good school and from there landing a great job. On the other hand if the teenager spends all of their time on social media or video games, that’s the bottom graph. They get small fixed amounts of pleasure, but that path leads towards the greater likelihood that they’ll incur some large cost in the future. Perhaps they won’t go to college at all, and end up in a crappy job, or, worse, living at home and unemployed. Obviously none of this is guaranteed, and outliers abound, but remember we’re trying to have a discussion at the level of the entire society.

Every parent who cares about doing a good job recognizes these trade-offs instinctively. We don’t make our children do hard things because we’re gunning for them. We make them do hard things and avoid short term pleasures because over the long run we think it will make them happier, more successful people. This is what all of the things I listed, and many more that could have been listed, have in common. They require short term pain but provide long term benefits. If your children do challenging things now they’ll be able to do challenging things later, and challenging things are rewarding, both monetarily and psychologically. On the other side of things we counsel against indiscretions, even small ones, because there’s always a chance they’ll lead to irreparable harm. No one tries drugs for the first time thinking they’re going to end up hopelessly addicted to opiods, but yet that does happen. (These days far more often than it should.)

We’ve managed to spend a lot of time giving examples of antifragile challenges, and even offering up charts, but we’re still a long way from defining at exactly what point exposure to stress and suffering goes from making kids stronger to harming them. Also it’s tempting to imagine that we can separate actually suffering from challenging activities when we seek to encourage resilience. And perhaps you can to a very limited extent, but while involuntary suffering may help you deal with voluntary challenges, I don’t think the inverse is true. I think there’s a danger in trying to move too much out of bucket one. This is the whole basis of the hygiene hypothesis with its connection to the rise of asthma and potentially fatal allergies.

As far as this post is concerned, we may have gone as far as we’re going to in defining the perfect amount of stress and suffering, and as I said, that isn’t very far. Part of the difficulty comes from the fact that this is a new problem. It’s only been very recently that we’ve had the option to adjust the level of stress and suffering across a broad enough area for it to make a difference. Accordingly we haven’t accumulated a lot of wisdom on which to draw from.

Historically the environment was challenging enough to give children all the stress and suffering they could ever possibly need in order to be strong — in order for them to be antifragile. And then in far too many instances went beyond that point to cause them harm or even death. Though it is interesting to note that from what we can tell psychological harm appears to have been rarer during those times. So it is good that we can now dial it back, but our tendency is always going to defer to the person who wants it to go the lowest. Which is to say advocating for more suffering — more things in bucket two, and especially bucket one — is always going to be difficult to defend.

This tendency to err on the side of suffering mitigation might not be so bad if our control and understanding of the nature of challenging children was more precise. But we don’t have the ability to fine tune challenges, particularly anything in bucket one, which as deBoer points out, continues to be a thing. And even voluntary challenges vary quite a bit in difficulty as a result of individual differences. There are a few kids who love learning to play the piano, most find it difficult and boring. All of this means that efforts to calibrate how challenging we make things are going to be very crude for the foreseeable future. Given this and our natural proclivity to lessen suffering, we should probably consciously create a counter-bias towards erring on the side of greater difficulty. Instead society has done the exact opposite, and in a way that largely overlooks the complexity and ramifications of this decision.

IV.

As we adjust the dials of suffering — using technology to move suffering from bucket one, or challenges from bucket two, into bucket three — we’re playing with a machine we scarcely understand. The goal is easy to understand: make the world better. And it’s obviously admirable. But our understanding of how moving the dials relates to achieving that goal is crude and incomplete.

This ties into another piece I came across recently which appeared to be making a point similar to mine:. The Social Recession: By the Numbers by Anton Cebalo. I ended my previous post by talking about the incel phenomenon and the staggering number of people not having sex. He uses that to open the piece and ties it to a larger phenomenon:

…a marked decline in all spheres of social life, including close friends, intimate relationships, trust, labor participation, and community involvement. The trend looks to have worsened since the pandemic, although it will take some years before this is clearly established.

The decline comes alongside a documented rise in mental illness, diseases of despair, and poor health more generally. In August 2022, the CDC announced that U.S. life expectancy has fallen further and is now where it was in 1996…even before the pandemic, the years 2015-2017 saw the longest sustained decline in U.S. life expectancy since 1915-18. While my intended angle here is not health-related, general sociability is closely linked to health. The ongoing shift has been called the “friendship recession” or the “social recession.”

What he describes fits under the broad definition of suffering. The decline in sociability robs us of tools to mitigate suffering. And the rise in poor mental and physical health, causes suffering we are therefore ill-equipped to deal with.

So how is it, if we’re turning down (what appears to be) the suffering dial, that actual suffering is going up? Are we sure we understand how the machine works? Could it be that we have no clue? To be clear I’m not claiming I understand the machine either. I don’t. But that’s precisely why I think we should be very wary about messing with the dials.

To take things from another direction Cebalo is arguing that our culture has become more fragile, and correspondingly less antifragile. Also that our fragile culture appears to be composed of fragile individuals. Of course, fragile things eventually break, which is what Cebalo is worried about, but given that our culture hasn’t broken yet, it must not have been fragile for long. What was the quality of culture before all the things Cabalo describes started happening?

The whole concept of antifragility comes from Nassim Nicholas Taleb, and for Taleb there are only three categories. Something can be antifragile, robust, or fragile. Fragile things, by their nature, don’t stick around for very long. Things that do stick around for a long time are therefore either robust or antifragile. In practice very few things are robust — neither harmed nor helped by stress — so long standing elements are generally antifragile.

Children have been around for a long time, and, as Haidt and Lukianoff point out, they’re antifragile. Much of what falls under the heading of culture, particularly as it stood 40 years ago, has also been around for a long time and is also probably antifragile. When something persists for a long time it evolves, a process that’s great at producing things that are antifragile. When this happens with culture we call it cultural evolution, and while we understand how it works, we don’t always correctly identify which elements of culture are antifragile products of this process and which are just dumb ideas some person in power came up with. To be more specific, when your thinking about something that used to happen but no longer does it can fall into three categories:

Barbaric relics of the past which never served a useful purpose.

Practices which are still useful, but we’ve incorrectly identified them as barbaric relics of the past, and dispensed with them.

Practices which were useful, but through progress and technology we have ended up duplicating their utility in some other way.

To take an example (as discussed in the previous post) dragging your disrespectful kid outside and walloping them, i.e. corporal punishment. Does this practice belong in category one, something that was never appropriate or useful? Category two? It’s still useful, but temporary cultural fads have incorrectly identified it as barbaric? Or category three? It was useful, but is no longer because we have different ways of punishing kids and/or the need for obedience is not life or death, like it used to be?

You may also notice some parallels between these three categories and the buckets we’ve been discussing, though it’s not perfect. But just like with the buckets, I think we’re bad at deciding what things should be in categories two vs. category three. We’re convinced we’ve grown beyond certain things, but in reality we might just be temporarily tired of them.

As to the separation between categories one and two, I’ve talked about that in the past, and this post has already taken way longer than it should to write. But perhaps you’re familiar with the case of manioc and cyanide. It’s a great example of cultural evolution. Tribes in South America who lived off manioc did things that seemed completely unnecessary (category one) but when the cyanide content of the manioc was actually tested it turned out that those, seemingly unnecessary steps were absolutely critical (category 2). Finally we can presumably eliminate the cyanide through industrial processing (category 3).

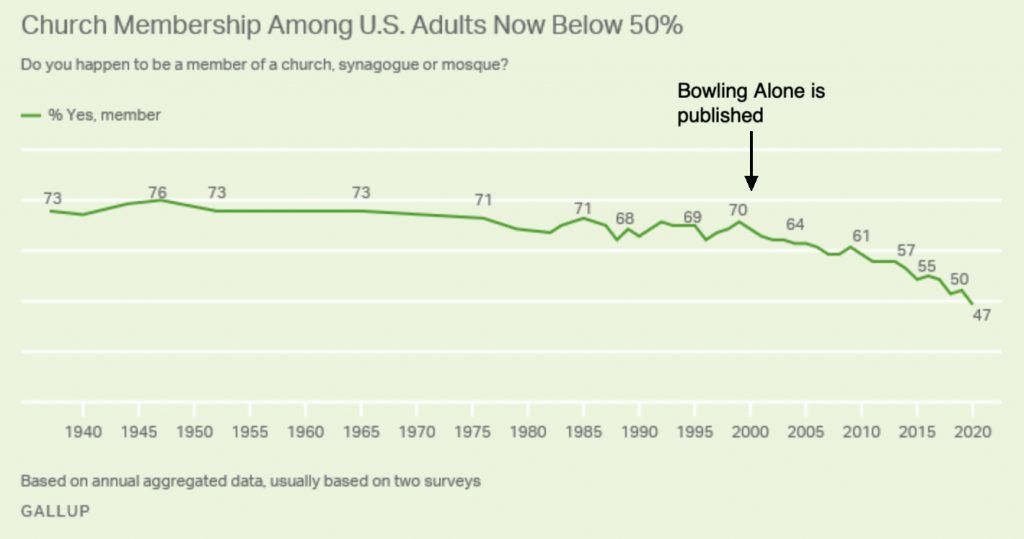

The point of the discussion of categories and manioc is the idea that it can be difficult to identify practices and behavior which result in antifragility. This is both the danger of turning dials and the ineffability of conservatism. We often sense that things are important without having the data to back it up. And from all of this we finally return to religion and church attendance. Which many people, including myself, strongly feel the importance of. Though also, fortunately, we also have some data. Returning to Cebalo’s post he makes a special point of highlighting the precipitous decline in church membership since the turn of the century:

As you can see from the caption he relates this decline to the larger point Robert D. Putnam brought up in his book Bowling Alone, but I think the decline in church membership has a larger impact than just one factor among many for the increase in loneliness. Though that’s certainly a non-trivial consideration.

Even if you think I’m misinterpreting the data. It would seem foolish to dismiss the trend in the chart above as inconsequential. Something big is happening. I suppose it could be because religion was always in category one, or that it has recently been successfully moved to category three, but given the incredibly long time it’s been around, I think it’s far more likely that it’s part of the culture that has evolved to make us antifragile. I.e. it’s in category two and society has dispensed with it to its detriment.

The chart is interesting and even startling, but it’s not the best evidence for the connection between religion and better mental health. There’s actually quite a bit of more direct evidence. To take just one example I recently came across a working paper titled: "Opiates of the Masses? Deaths of Despair and the Decline of American Religion”. Here’s the abstract:

In recent decades, death rates from poisonings, suicides, and alcoholic liver disease have dramatically increased in the United States. We show that these "deaths of despair" began to increase relative to trend in the early 1990s, that this increase was preceded by a decline in religious participation, and that both trends were driven by middle-aged white Americans. Using repeals of blue laws as a shock to religiosity, we confirm that religious practice has significant effects on these mortality rates. Our findings show that social factors such as organized religion can play an important role in understanding deaths of despair.

So religion helps us deal with despair. I understand the leap I’m taking when I make that assertion. But perhaps as we draw things to their conclusion you’re willing to entertain the idea that religion is an important source of antifragility. That in making us do small hard things it enables us to do large challenging things, and moreover to survive the intense, involuntary suffering that is still humanity’s lot. Religion doesn’t just provide practice at attending long, boring meetings, though I understand that it often gives that impression, it’s part of a whole network for doing challenging things, and mitigating suffering. It’s how we used to do hard things as a community, and through its transition to civic religion it’s how we still occasionally do hard things, though that form of religion is fraying as well.

Sure, as many people brought up, it’s also a hard thing to leave a religion, and that probably gives an individual a certain amount of toughness, but we’re not interested in individual toughness, eventually any truly great endeavor requires societal toughness. And here, at the very end, I would like you to take a moment and reflect on how tough your ancestors were. And how much they probably suffered for their religion. Why? Because however much they suffered, religion offered relief from even greater suffering. It helped them deal with despair. It’s part of what made them tough. And yes it’s a good thing that we’ve been able to move things out of bucket one, that our children no longer die, that plagues are mild, and famine is rare. But in exchange, is it too much to ask that our children sit still for a couple of hours every week and do their best to understand the faith of those incredibly tough ancestors?

Paying for writing is one of the many things which got moved out of bucket one by the internet. Now you can choose whether to bear a cost for writing. You get to choose whether it should be bucket two or bucket three. I think the mere fact that I explained the buckets to you should make it a bucket two item.