Review: Nate Silver, The Election, and "On the Edge: The Art of Risking Everything"

He talks about the Village, and the River, but what we really need is a Redoubt.

On the Edge: The Art of Risking Everything

By: Nate Silver

Published: 2024

576 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

There are two different ways of approaching the world: the River, which thinks in terms of numbers, expected values, and quantification and the Village, which is the paternalistic expert class which manifests as the vast bureaucracy.

What's the author's angle?

I got the impression that Silver just wanted to write about things that interested him. Because of this, his thesis was kind of tacked on. That said, he is a fairly passionate advocate for things that interest him.

Who should read this book?

Silver is worried that people will skip the first half of the book which is about gambling, but in reality that was the best part, or at least the part I found to be novel. The second part is about Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF), AI, and all the stuff you’ve already heard too much about if you spend much time online. With this in mind, I think there are three reasons to read this book:

If you want a deep exploration of high-level poker playing.

You have never heard of AI Risk or SBF.

If you think my discussion of Silver’s model of the Village vs. the River is incomplete.

Specific thoughts: An mashup of the election and this book

As a continuation of my experimental phase, I thought I’d try to mash together this book review with some thoughts on the election.

Obviously I’m far too slow on both counts. There have already been a million takes on the election, some quite good. And there have also been several excellent reviews of On the Edge. But perhaps by combining the two I will achieve some useful alchemy that neither could achieve when attempted separately. But before we get to that, I need to tell you a story.

I- An Analogy For the Election

This story takes place late in 2011. At the time my business partners and I were considering an acquisition offer. Here’s the relevant section from the writeup I did on the whole long saga a while back.

When my story begins I’m in a business with three other partners (four guys total). One of the partners has given up on the business, forcing us to consider — and as you’ll see eventually accept — an acquisition offer from a local startup that he arranged, and which was very beneficial to him. The story of that partner and indeed how I arrived at that spot, will have to wait for another time, he will not come up again. As far as the other two partners and the rest of the characters, I have decided [controversially] to use characters from Brooklyn 99 as stand-ins…

As Peralta, Boyle, and I considered the acquisition offer, right out of the gate we made two critical mistakes. I’d rather not admit my big mistakes, but this post will be full of them and perhaps those that follow in my footsteps will glean some wisdom from them. The deal coupled a small amount of cash with, what we thought, was a large amount of stock. Of course, as we all learned from The Social Network, thousands of shares of stock are meaningless if there are millions of shares outstanding. Now at the time I did, repeatedly, ask to see the 99’s cap table. The Vulture kept promising to get it to me, but he never did, and I didn’t make that our line in the sand. But I should have.

Ultimately the 99 didn’t have a liquidity event or any kind of exit so it didn’t matter, but part of the reason we were doing the deal, despite our misgivings, was the idea that we might get rich from it. Much later I did see the cap table and it turned out that we each owned a mere 0.21% of the company. So given that my “I can retire amount” was at least $3 million, to have reached that goal the company would have to be worth a minimum of $1.5 billion, and that assumes no further dilution. This was never going to happen.

The important takeaway is that the deal seemed very sensible. Our current business was not in great shape, and the departing partner was in charge of sales. So, if we turned down the deal, things would go from bad to worse. We also thought (erroneously) that there was a chance we could make a lot of money. Finally, this startup had raised a significant amount of capital, so we would go from a situation where getting paid was always a little bit dicey to a steady, well- paying job for the foreseeable future.

Despite this, we had misgivings. The CEO of the startup couldn’t really explain what the startup was going to do without using sentences where “Facebook” and “Amazon” got combined with a lot of vague enthusiasm. The three of us knew that turning down the acquisition was a dumb move, but one of my partners summed up the situation when he said, “I just want to be in a position where I can say F-you once in a while.”

II- Harris vs. Trump

Whether or not America is in the position to say F-you, I think that’s what a plurality of people did.1 In other words, this story is a great analogy for the election. Harris was clearly the sensible option. But I think people are tired of the “sensible” path, and particularly the hectoring tone and sanctimony that accompanies being sensible.

Despite this, being sensible has a lot going for it, so yes, I wanted Harris to win. I’m aware of all of the objections. And I didn’t actually vote for Harris.

(I voted for Chase Oliver. Utah was also the only state where Lucifer “Justin Case” Everylove was on the ballot. As you might imagine I was tempted.)

I had some of the same misgivings about Harris that I had about that CEO all those years ago. She certainly had a pitch that was long on enthusiasm and light on details. That said, even saying I wanted her to win is going to annoy many of my readers (though certainly not all). But for me it came down to basically two things:

Given that the Republicans were all but guaranteed to take the Senate, a Harris presidency would result in a divided government that couldn’t cause too much trouble. Also, whatever trouble Harris was going to get up to didn’t seem like it would be any worse than the trouble we’d already survived with Biden.

A non-partisan assessment of the potential impact of both candidates on the national debt came to the conclusion that Trump was likely to raise the debt by a lot more than Harris. Now the ranges were large, and these days can assessment claim to be completely bias free? Nevertheless it seemed like the best estimate I was likely to get, also it feels right to me. Trump wants to protect Social Security and cut taxes. And we can’t keep ignoring the debt.

Number two may be years away, but number one has already taken place. The Republicans have taken the Senate, and it looks like they’ll be operating with the barest of majorities in the House. I guess we’ll wait and see on the debt, but as of this writing it stands at $35.97 trillion. I’ll be shocked if it’s less than $40 trillion when Trump leaves office. And I’m willing to place bets on that.

But, you might ask, what about the Department of Government Efficiency? Or DOGE as people like to call it? Won’t Musk and Ramaswamy come in and slash the deficit thereby reducing the debt?

I suppose anything is possible, but I suspect that the effort is going to be a lot more difficult than people think. But I will agree there are some potential positive black swans that might emerge from a Trump presidency. This is the central feature of Trump: he’s high variance. You can imagine that he’s such a maverick that he’ll be the one to finally smash through the permanent bureaucracy and break us out of our long slow slide into decadence—that he might in fact be our only hope.

Contrariwise you can also imagine that he’ll appoint a bunch of toadies to high office who are only there to serve his narcissistic agenda2—that rather than surrounding himself with visionaries he’ll surround himself with bootlickers. I think his cabinet picks lean towards the latter, particularly Matt Gaetz, but I’m sympathetic to the argument that it’s too early to tell.

If you’ve really been around for a really long time you may remember that one of my big worries when it comes to selecting presidents is their potential for starting World War III. I’ll admit I don’t know who’s better on this count. I think most people feel like Trump is the bigger danger. One could certainly imagine Trump forcing peace on Ukraine and giving up Taiwan to China, but one could also imagine that this is precisely the kind of thing that prevents WWIII. And who knows what’s going to happen in the Middle East.

Much of this is to say that we don’t know what the future holds. Freddie deBoer makes the argument that no matter how bad you think Trump is, George W. Bush was much, much worse. He makes a compelling case.

III- The River and the Village

It’s finally time to return to the book. As I mentioned, the central metaphor of the book is between the kind of safe controlled society which Silver refers to as the Village, and the rough and tumble risk takers who sail up and down the River. In Silver’s words the Village:

…consists of people who work in government, in much of the media, and in parts of academia. It has distinctly left-of-center politics associated with the Democratic Party.

In other places he calls it the indigo blob. In my framing, it’s all of the “sensible” people.

He has no such pithy definition for the River, and in fact splits it into four different subsections, each with its own characteristics. But here are some of the things all the sections have in common:

They speak one another’s language with terms such as expected value, Nash equilibriums, and Bayesian priors.

How do people in the River think about the world? It begins with abstract and analytical reasoning.

…people in the River are often intensely competitive. They’re so competitive, in fact, that they make decisions that can be irrational, gambling even once they’re essentially already set for life (think about Elon Musk’s decision to buy Twitter when he was the world’s richest person and then one of its most admired).

It seems pretty clear based on this that Harris represents the Village, but does this mean that Trump represents the River? Certainly lots of Riverians, like the aforementioned Musk, ended up backing him. Obviously part of that is because of the antagonism between the Village and the River which Silver mentions—the Village seems to be inhibiting the creation of a lot of cool stuff—but that’s certainly not the whole story. I think one of the under-discussed reasons they backed him is because of his high variance. If On the Edge were distilled down into four words, they would be: “Riverians like to gamble”. And Trump is a huge gamble. I’m not sure what the odds on that gamble are, but I guess they figured anything beats another four years in thrall to the Village.

A Harris supporter might point out that high profile Trump supporters can afford to gamble. Even if they’re wrong and they lose big, they’re going to be fine. But of course Trump wouldn’t have won if he only had the support of disaffected Riverians, there were also vast masses of people who had finally had enough of the Village. Who decided they were sick of being “sensible” and that the time had come to just say F-you to the whole thing.

We’ll see if the 2024 election ends up being the triumph of the River, but from my vantage point it’s far more obviously the repudiation of the Village. People are already talking about the possibility that the Republicans will overinterpret the strength of their mandate, and I expect Riverians will fall into the same trap. To put it into terms they will understand the Riverians have won a very consequential side bet, but they haven’t won the whole game. There are still a lot of chips in the center of the table.

Given that we’re now all part of this Trump bet, whether we like it or not, I’m hoping it works out, but if we’re going to hope that Trump is the avatar of the River, and all the stuff that comes with that we need to look at the weaknesses of the River as well as its strengths.

IV- The River and Its Rapids

As you may have already gathered from the “Who should read this book” section. I was not a huge fan of the book. Let me try to sum up why.

On the Edge spends an enormous amount of time advocating for the River, and to Silver’s credit he does mention some of the excesses of this approach. For example he spends quite a bit of time discussing Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF)—a Riverian who caused a significant amount of harm. But as part of this discussion he never explains why SBF is an outlier. More broadly, while he acknowledges the excesses of the river, he never offers up any suggestions for how these excesses might be curbed. It’s possible he’s making the argument that a Riverian approach, despite its occasional failings, is, on net, good, but if so he never makes that argument explicitly.

He does spend time urging people to understand the difference between a calculated risk, and a reckless gamble, but he also admits (correctly) that it’s not always easy to tell the difference. As a stark example he spends quite a bit of effort trying to understand AI risk, including interviewing Eliezer Yudkowsky, before eventually admitting that he’s not sure if AI is a calculated risk, or a reckless gamble.

It’s good that he doesn’t entirely ignore the problems caused by excessive risk-taking, but it is weird that he spends so much time on SBF while spending so little time on the broader question. As one example, in the intro he mentions that one critique of the River might point out its role in the 2007-2008 financial crisis. Not only does this seem like a pretty big critique, but also a completely fair one. The crisis pulls together all of the elements Silver mentions as being associated with the River: risk taking, an excessive focus on expected value, the extreme competition of Wall Street, etc. But other than that one brief mention he never brings it up again.

I didn’t necessarily need him to offer a defense of this particular failure (though it would have been nice, it does seem like the elephant in the room) but I expected him to offer up a more robust defense of the River in general. Instead he seems fine with advocating for the Riverians, describing their failings, and shrugging his shoulders. You can see this most clearly in his discussion of SBF. It’s clear that he thinks SBF leans towards the reckless side, but he doesn’t give any pointers for where exactly SBF went wrong. It gets so bad that one longs for Silver to trot out the No True Scotsman fallacy, because at least it would be a position.

I don’t think this is a mistake, or an oversight, in fact I think it’s right there in the title: “The Art of Risking Everything.” It’s hard to make any other interpretation than that “The Art” is synonymous with the River, and SBF was indeed willing to risk everything. One of his most famous positions is that he:

…would be happy to flip a coin, if it came up tails and the world was destroyed, as long as if it came up heads the world would be like more than twice as good.

I’d rather not “risk everything” if that’s okay with you.

V- A Third Location: The Redoubt

Obviously not everyone can be classified as a Villager, or a Riverian. Most people who voted in the election are neither. As such some of the critiques of this book try to imagine how to classify the vast masses of people who just want to have a decent life, and don’t give much thought to which “locale” might provide that life.

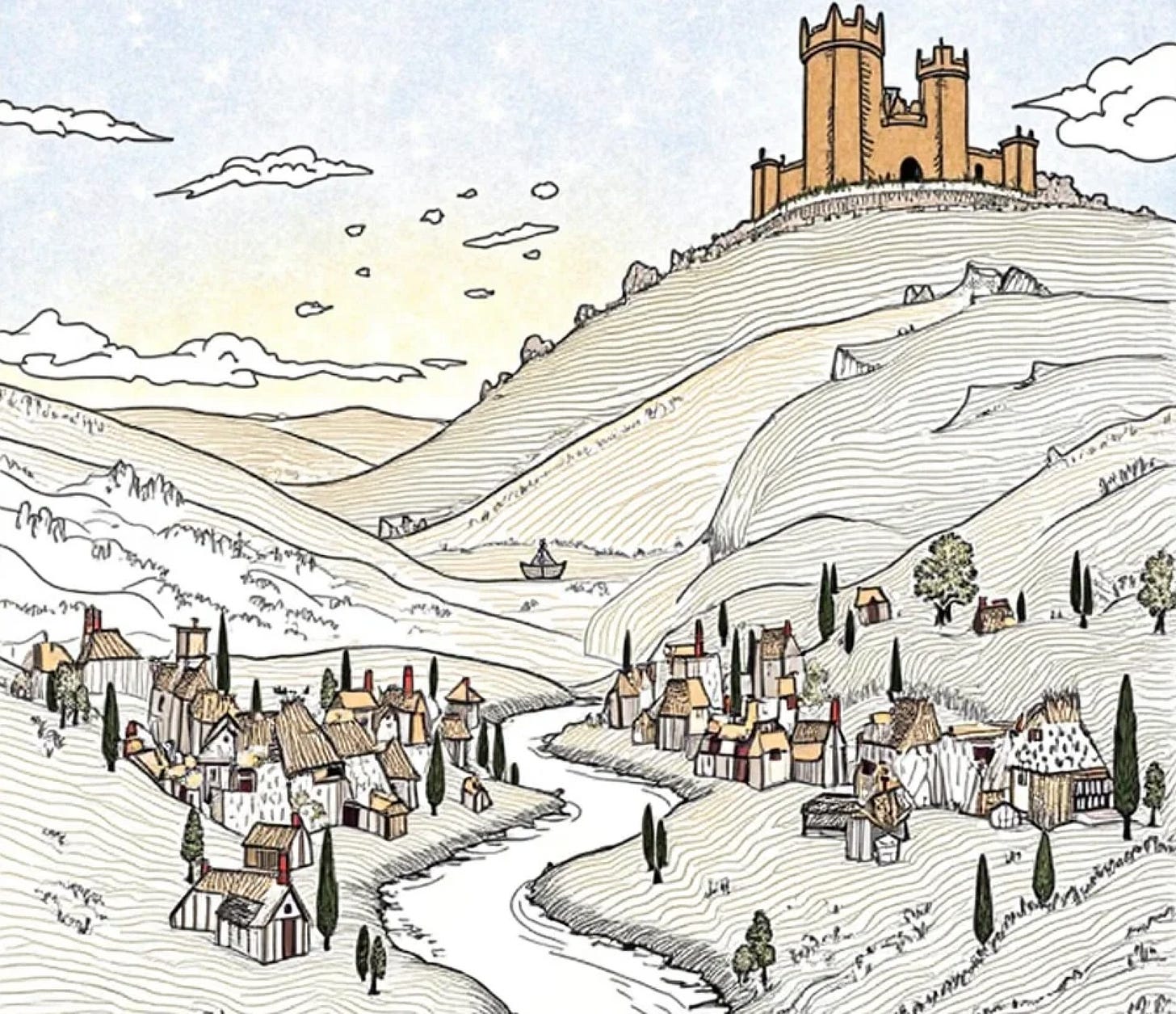

I’m not going to go in that direction. Rather, if we’re going to talk about elite obsessions, which both the River and the Village are, then I would like to propose a third location: the Redoubt. Calling it a castle or even a monastery would also be appropriate. I’m not sure what to call the inhabitants of this location, maybe just the Doubters. People who doubt that the gambling of the Riverians, or the rigid control of the Villagers will solve all of our problems, and that rather they might actually create many of them. Given this, on a hill high above the Village and overlooking the River, there needs to be a Redoubt. A place of security for when the River spawns pirates or the Village spawns a witch hunt.

As you might already be able to tell, the analogy is not perfect (but neither was Silver’s original) nor is it entirely clear what behavior makes someone a Doubter (other than doubt itself). But this was what was missing from the book: how do you keep the excesses of the River and the Village from blowing up the world? In the former case metaphorically through things like the 2007-2008 financial crisis, and in the latter case perhaps literally with its increasing entanglement in Ukraine’s war against Russia.

As this touches on my central point about avoiding nuclear war, it’s worth pausing here for a moment to examine this entanglement. Biden recently authorized Ukraine’s use of US-made long-range missiles to strike inside Russia itself. While at the same time Putin has lowered the threshold for using nuclear weapons. Both of these decisions follow a format similar to previous declarations. Both are incremental steps on a path we’ve already traveled quite a ways on, so perhaps there’s no cause for concern. But it is by such incremental steps that great distances are traveled. To be clear, the situation in Ukraine is not an easy one, but if anything that strengthens the case for a Redoubt rather than weakening it.

None of this is to say that the Redoubt is going to be easy to build, if it were, we would have done it already. But I believe we need some place to escape the totalizing ideology of the Village, a place which also hedges against the risks of the River. Such a place would actually enhance our ability to take advantage of both the Village and the River. To put it another way: ideologies are good, total thought control is not. Risk is good, risking everything is not.

Much of the reason for why the election seemed so consequential, and its aftermath so dire, or alternatively, so liberating, is that all of this appeared to be on the line: ideology, risk, the future of the country. All of our hopes and dreams seemed to hinge on a single vote. So perhaps the place to start with the Redoubt is just by carving out a spot of land where everything isn’t on the line. Where the whole world doesn’t hang on a single Tuesday in November.

You may be surprised that I wrote a whole post about Nate Silver, and the election without ever once mentioning his role as one of the premier election forecasters. Well you’re not alone I was surprised as well. If you’re interested in continuing to follow along as I fail to mention obvious things in favor of the more obscure please subscribe. And if you have subscribed. You should also know there’s a huge archive of posts full of obscurities, you should check them out.

As of this writing Trump got 49.87% of the popular vote as compared to 48.25% for Harris.

I was speaking with a Trump supporter the other day, someone whose opinion I greatly respect and when I mentioned Trump’s narcissism, he countered that all politicians are huge narcissists. This is true, but Trump is nevertheless different, and it was only later that I put into words how he’s different. Most narcissists exist in tension with the opinion of their peers. They can be talked out of things, they feel shame. Other politicians may be Trump’s equal in narcissism, but the difference is that Trump experiences only the tiniest amount of tension. Sure you hear stories of him being talked into things—apparently his son and Tucker Carlson talked him into picking J. D. Vance—but that’s precisely why you hear about them. They’re so rare as to be noteworthy. For every other politician making decisions by consensus is the norm. Now of course that also drives them to be overly sensitive to polls, public opinion, and the judgements of their peers. Trump cares far less about these things. It’s one of the things that makes him so appealing, but unless his instincts are infallible (which they’re not) over the long run it’s a huge weakness.