Mid-length Non-fiction Book Reviews: Volume 4

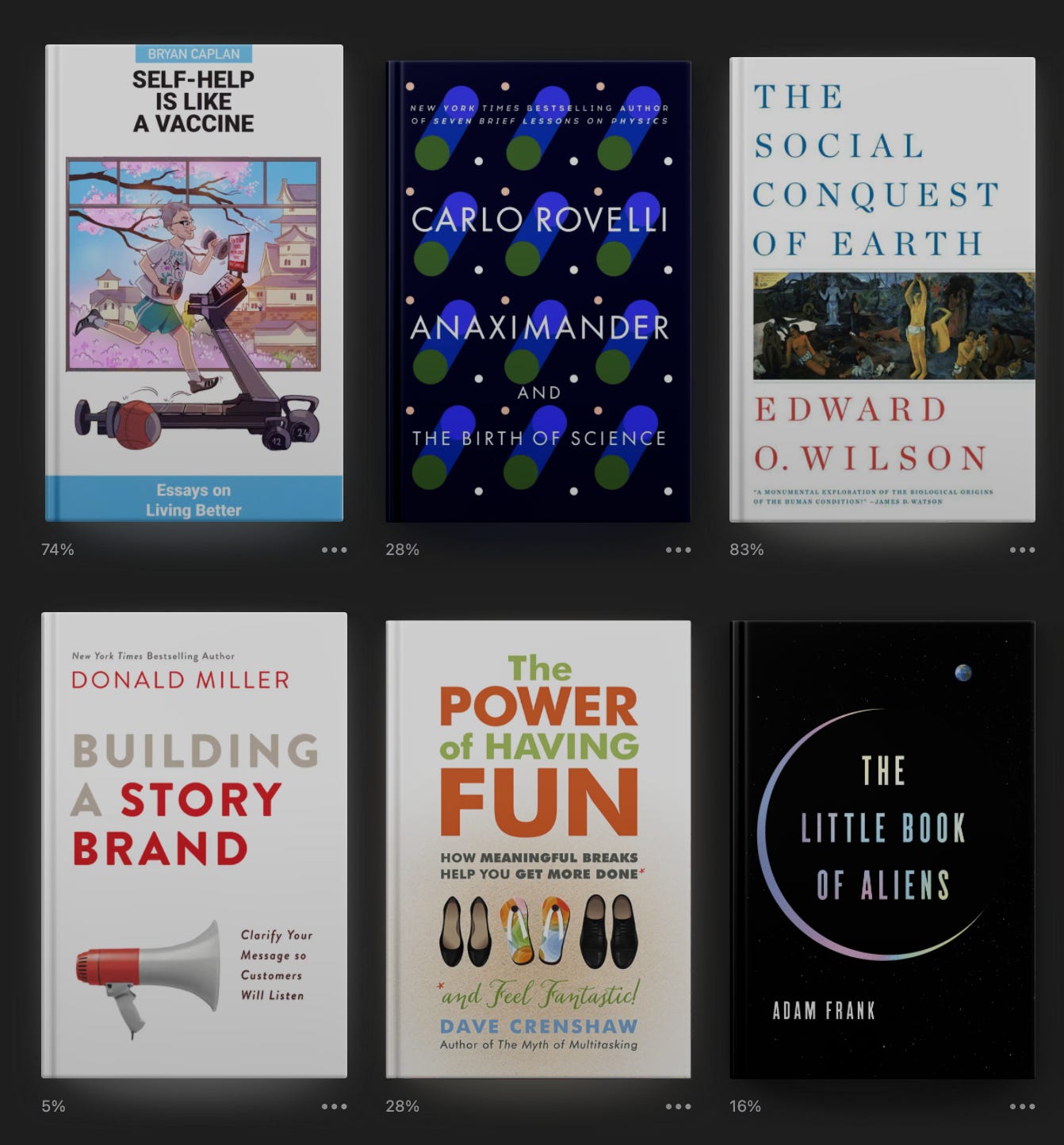

Bryan Caplan, the birth of science, eusociality, a page a day book, StoryBrand, how to 10x your productivity by playing World of Warcraft for 30 minutes a day, climate change and aliens!!

Self-Help Is Like a Vaccine: Essays on Living Better by: Bryan Caplan

Anaximander: And the Birth of Science by: Carlo Rovelli

The Social Conquest of Earth by: Edward O. Wilson

The Intellectual Devotional: Revive Your Mind, Complete Your Education, and Roam Confidently with the Cultured Class by: David S. Kidder and Noah D. Oppenheim

Building a StoryBrand: Clarify Your Message So Customers Will Listen by: Donald Miller

The Power of Having Fun: How Meaningful Breaks Help You Get More Done by: Dave Crenshaw

The Cartoon Introduction to Climate Change by: Yoram Bauman and Grady Klein

The Little Book of Aliens by: Adam Frank

Self-Help Is Like a Vaccine: Essays on Living Better

By: Bryan Caplan

Published: 2024

206 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

A collection of Bryan Caplan’s essays covering various, somewhat-quirky rules he has for improving your life. One such example, if you’re single he recommends you should only date within your sub-sub-culture.

What's the author's angle?

Bryan Caplan is one of the GMU crowd with Tyler Cowen, Alex Tabarrok, and Robin Hanson. They’re all economists with what amounts to an autistic view of the world. (And I mostly mean that as a good thing.)

Who should read this book?

If you’re looking for some of the most cold-eyed advice out there, this might be the book for you.

Specific thoughts: I’ve always thought Caplan could do with a little bit more humility

This is only the second book I’ve read of Caplan’s, but I’ve read lots of his blog posts, and I feel like I’ve always been able to detect a touch of arrogance in everything he writes. If I were to distill it into an assertion, it’s the arrogance of being sure you have life figured out. (And moreover that you’re a bit baffled that other people haven’t.)

The starkest example (and perhaps this is cheating) comes not from this book, but in the form of his long-running debate with Scott Alexander over the reality of mental illness. Caplan argues that mental illness is just a preference. He doesn’t go into exactly that topic in this collection, but he has some things that end up being close to it. For example, he argues that if you underestimate the risk of something you should do less of it, and if you overestimate the risk you should do more of it. And then he specifically mentions cigarettes.

He needs to discover a discrepancy between actual and perceived downsides. Do you under-estimate the health risks of smoking? Then economics tell (sic) you to smoke less. Do you over-estimate the health risks of smoking? Then economics tells you to smoke more. Unlike doctors, economists know how to give advice and respect pluralism at the same time.

I get what he’s saying, but he picked a really weird example to illustrate his point. Particularly given that smoking has been so demonized that 99.5% of people overestimate the risks. I know he’s not saying 99.5% of people should smoke more, but you would be forgiven for reading it that way.

Much of the advice in this book seems similarly counter-intuitive. This is both its great strength and its great weakness. Certainly you want access to advice outside of the mainstream, particularly if it might work. But that also means that the advice is very personalized and might not work for anyone other than Caplan himself.

Anaximander: And the Birth of Science

By: Carlo Rovelli

Published: 2023

272 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The history of science, told through reference to its pivotal personalities. In particular Anaximander who, despite being born in 610 BC, made several very critical contributions to the scientific method.

What's the author's angle?

Rovelli describes himself as “serenely atheist” and his advocacy for humanism is very much apparent in this book. This includes spending more time than might otherwise be necessary picking a bone with religion.

Who should read this book?

This feels like one of those books that could have just been a series of blog posts. Which is not to say I didn’t enjoy it, more that it seemed like Rovelli was stretching things. I can almost imagine that’s how he ended up with so much criticism of religion. “We’re only at 100 pages! What else can I add!”

Specific thoughts: Anaximander certainly did have a lot of firsts.

I suspect that the previous sections sounded fairly critical, which may give you a mistaken impression of things. I did enjoy the book, especially the first two-thirds which focused more on the “Birth of Science” stuff. In particular Rovelli makes a powerful case for Anaximander as the first scientist. Consider some of the things he did:

He was the first to come up with the concept of water evaporating and later falling as rain.

He proposed a proto-theory of evolution which included the assertion that life emerged from the sea.

Unlike basically everyone else who thought the Earth was supported somehow (backs of turtles for example) Anaximander was the first to imagine that it floated unsupported in space.

Most importantly he was the first to describe natural phenomena as proceeding from natural forces without any reference to gods.

This approach was carried down to better known philosophers like the big three: Socrates, Plato and Aristotle. Rovelli makes a compelling case that it was this revolution in thought that got the ball of science rolling.

One very compelling illustration of this comes from comparing Anaximander to the Chinese Imperial Astronomical Bureau. Despite conducting detailed observations of the heavens for at least two thousand years, the Chinese did not come up with the “unsupported in space” idea until the Jesuits arrived in the 17th Century.

The Social Conquest of Earth

By: Edward O. Wilson

Published: 2013

352 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

A broad ranging examination of eusociality—cooperative care of offspring, division of labor, and central “nests”. Wilson is an expert on eusociality among insects (bees, ants, etc.) and he brings that expertise to humanity.

What's the author's angle?

A significant portion of the book is dedicated to a defense of group selection, as opposed to gene-based selection. (What’s often called the selfish gene after the book of the same name by Richard Dawkins.) Wilson also seems to view this as an opportunity to hold forth on nearly everything.

Who should read this book?

Parts of this book should be read by anyone with an interest in science, and parts of the book should only be read by fans of Wilson, or people willing to be somewhat forgiving as he pursues his hobby horses (see below).

Specific thoughts: Wilson tries to connect too much, and the connections he makes are tenuous.

Wilson has done truly incredible work in biology, evolution, eusociality, group selection, myrmecology and melittology.1 And when it's focused on these areas this book deserves to be ranked with other seminal works of popular science. When it wanders away from those areas, it’s still pretty interesting, but I think it suffers from a preoccupation with the cultural landscape of 2013 that will cause parts of the book to age poorly.

I found these discursions annoying. In part this is because of the anti-religious tone he takes. This not only annoyed me because I’m religious, but because of the way he goes about it. He acknowledges that cultural evolution is a major component of humanity, and one of the ways our eusociality is expressed. And he even mentions many benefits of religion, which should make me happy. But he also attributes numerous harms to religion, and it’s not always clear how he decides to lay some negative outcome at the feet of religion rather than culture more broadly (say for instance nationalism instead).

But I was feeling annoyed even beyond the protectiveness generated by my own religious bias, and it took me a while to pinpoint the cause. I think I was finally able to nail it down. I frequently read books where someone makes an audacious claim, and then they follow it to see where it leads. Even if I disagree with the claim, it’s always interesting to see where it might lead. I’m even more happy when the destination ends up being unexpected.

Wilson makes some interesting claims, though I wouldn’t necessarily call them audacious. But rather than following these claims to interesting places he seems to jump to various conclusions without much connective tissue between initial claims and the conclusions. This would be fine if his conclusions were interesting or thought-provoking. Instead all of his conclusions just happen to be exactly what you’d expect from a liberal academic in 2013. For example explaining national inequality with reference to Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel. That’s a fine book, and it’s a reasonable explanation for the inequality, but it has nothing to do with eusociality. But it’s an example of a tone that runs through the book that smart people have figured things out, and you just need to trust us.

Consider this description of how science works. Something which looks touchingly naive post replication crisis:

The successful scientist thinks like a poet but works like a bookkeeper. He writes for peer review in hopes that “statured” scientists, those with achievements and reputations of their own, will accept his discoveries. Science grows in a manner not well appreciated by nonscientists: it is guided as much by peer approval as by the truth of its technical claims. Reputation is the silver and gold of scientific careers. Scientists could say, as did James Cagney upon receiving an Academy Award for lifetime achievement, “In this business you’re only as good as the other fellow thinks you are.

But in the long term, a scientific reputation will endure or fall upon credit for authentic discoveries. The conclusions will be tested repeatedly, and they must hold true. Data must not be questionable, or theories crumble. Mistakes uncovered by others can cause a reputation to wither. The punishment for fraud is nothing less than death—to the reputation, and to the possibility of further career advancement.

In general I enjoyed the book, and I would describe it as being mostly diamonds with a little bit of rough, but sometimes that rough can be really rough…

The Intellectual Devotional: Revive Your Mind, Complete Your Education, and Roam Confidently with the Cultured Class

By: David S. Kidder and Noah D. Oppenheim

Published: 2006

378 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

It is intended that you read one page of this book every day. Each page is a short article on some topic or person. For example “The Resurrection of Jesus” or “John Steinbeck”.

Who should read this book?

If you’re a fan of the daily devotional, this is a interesting addition to the genre.

Specific thoughts: Sometimes the more you learn the less there is to be taught

It’s said that the more you learn the more you realize you don’t know. That’s mostly the case, but as part of that you need to be able to direct your knowledge acquisition towards your intellectual terra incognito.

It’s often not the case when you’re consuming something designed for a general audience. All of which is to say that my big complaint with this book was that a lot of the articles covered topics I was already familiar with, and when that was the case it was rare to come across anything really new on the subject.

Building a StoryBrand: Clarify Your Message So Customers Will Listen

By: Donald Miller

Published: 2017

240 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The idea that if you want to “sell” anything—be it a product, a service, or an idea— that you will find the most success structuring your pitch using the classic, seven-part story arc.

Who should read this book?

It feels like there are dozens of books with the general tag “If you’re a business owner, you have to read this”. I try to keep my pantheon of “must read business books” at fewer than twenty books, but even with that more limited criteria I think this book still belongs on that list. It is one of the few books where I immediately thought: I need everyone in my company to read this!

Specific thoughts: Everyone thinks they’re the Hero, to be successful at selling you need to take the role of the Guide.

According to Miller most stories have seven parts:

A Character/Hero

Has a Problem

And Meets a Guide

Who Gives Them a Plan

And Calls Them to Action

That Helps Them Avoid Failure

And Ends in a Success

Everyone imagines that they’re the Hero, and this includes companies. As a result most marketing material frames things as the heroic journey of the company.

“Founded in 1873 by an illiterate Civil War Veteran, Veridian Dynamics is an innovator in…”

Miller points out correctly that your customer obviously sees themselves in the role of the hero. As the saying goes “Everyone's the hero in their own story.”2 So if you try to play the hero, at best you’re just going to create narrative friction. At worst you’re going to set up a sense of competition between your customer’s business and your own.

Instead you have to position yourself as a guide. You’re the Obi-wan to their Luke. You’re the Dumbledore to their Harry. You’re the Virgil to their Dante.

This is the key insight of the book, and possibly just reading this brief description gets you 80% of the way there. But the insight is big enough that it’s worth spending 240 pages (five hours on audio) to delve into every nook and cranny.

The Power of Having Fun: How Meaningful Breaks Help You Get More Done

By: Dave Crenshaw

Published: 2017

192 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Your working day can be viewed as a desert you’re trying to survive. Anyone crossing a desert needs to occasionally stop at an oasis to rest and recover. “Meaningful breaks” are these oases.

Who should read this book?

If you have trouble justifying breaks, or if you think that your breaks need to be more meaningful, this book will probably help with that.

Specific thoughts: The problem is the lack of oases, it’s that there are too many faux oases, and once you’ve stopped it’s hard to get started again.

I really liked the framing that a break should be viewed as an oasis in the desert. I think that analogy is very useful. And it was also useful to be reminded that it’s not just you that must occasionally stop at an oasis. You should also have couple oases (date nights) and family oases (excursions and vacations).

All of this was good, but I don’t think Crenshaw talked enough about the central challenges: how do you tear yourself away from the oasis? And what counts as a true oasis? One of the examples he gave was of someone who worked 80 hours a week, but upon probing admitted that 20 hours of that was playing World of Warcraft, in secret. This gentleman expected that Crenshaw would tell him to stop playing WoW, but instead Crenshaw identified it as an oasis. He told him to keep playing WoW but to cut back to only playing 30 minutes every day before he headed home.

It sounds like this worked pretty well for this guy, but I’m thinking:

30 minutes is not a lot of time to play WoW.

Does he ever have problems stopping at 30?

I’ve known a lot of people who got pretty addicted to WoW.

If WoW counts as an oasis does watching YouTube count?

What about social media?

How often have you heard of someone who got on social media and next thing they knew an hour and a half had gone by?

I do think that there is a lack of true leisure in the world right now—emphasis on the word “true”. The challenge is not taking breaks, it’s taking meaningful breaks, and despite that phrase being part of the title, I don’t think Crenshaw had enough to say about the “meaningful” part of that challenge. (To be fair it was written in 2017, and a lot has changed since then. TikTok only really took off in 2018.)

The Cartoon Introduction to Climate Change

By: Yoram Bauman and Grady Klein

Published: 2014

216 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Pretty much what the title says… An introductory text on climate change using comics. I guess technically this would be graphic non-fiction?

What's the author's angle?

I know Bauman personally and he’s a super nice guy who’s not an alarmist or a radical, he’s an economist! (And a stand-up comedian. “The world’s first and only stand-up economist!”) As an economist mostly he wants to put a cost on externalities, so in addition to this book he’s also working on implementing a carbon tax. (You can find out more about that at Clean the Darn Air.)

Also I can’t help but mention that he has an ongoing bet with Bryan Caplan. (The subject of the first review in this post.) One of Caplan’s claims to fame, and the source of at least some portion of his aforementioned arrogance is the fact that he has never lost a bet. Bauman’s bet doesn’t resolve until 2030, but at the moment things are looking really bad for Caplan.

Who should read this book?

Probably everyone. I mean if you’re deep in the weeds, or even reasonably well educated about global warming, most of it is not going to be new, but it’s such a consequential issue, and the book is so tightly constructed and easy to read that I think everyone could benefit from perusing it.

Specific thoughts: I think a lot of issues could benefit from this format.

Who doesn’t like pictures? Who doesn’t think graphs improve non-fiction books? Who doesn’t want subjects to be more accessible? What if you were able to get all three things in a single format? Such is the promise of graphic non-fiction, so far every book I’ve read of this sort has been great. This is the case even if I disagreed with it. (Would you believe it? It was another book by Caplan.)

All of which is to say that in addition to recommending this book, I would recommend this format more broadly, and I think Bauman was smart to choose it.

The Little Book of Aliens

By: Adam Frank

Published: 2023

240 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

An overview of the search for both extraterrestrial life and extraterrestrial civilizations, with a good overview of most of the issues. (Fermi’s Paradox, UAPs, Drake Equation, etc.)

What's the author's angle?

Frank is a disciple of Drake and has been heavily involved with official searches for exoplanets, evidence of life and technosignatures.

Who should read this book?

This is not the best book on Fermi’s Paradox. (That’s The Great Silence by Ćirković—review here.) This is probably not the best book about exobiology or the current UAP phenomenon. But it may very well be the best book to cover all three of those issues (and more!)

Specific thoughts: The recent UAP/UFO sightings are probably not aliens

I am a UAP/UFO skeptic. Which these days mostly means I don’t think they represent visitors from another world. Frank shares this skepticism, which is nice, because for a while there it seemed that everyone was suddenly a believer.

Frank covers a lot of reasons for his skepticism, some that are widely acknowledged and some that are obvious only if you think about it. (A set which apparently includes Frank and me and no one else.) Finally there were a couple of objections that I hadn’t heard, and those were worth the price of the book.

In the widely acknowledged category we have things like the vastness of interstellar distances, the unreliability of eyewitness accounts, the evidence which gets ignored, etc. These get brought up, but far too infrequently.

The Frank and me category is more interesting and includes things like how do you explain their evident desire to hide, but also the fact that they’re so bad at it? Related, how are they crossing the vast interstellar distances without leaving any trace, while leaving all sorts of evidence of their far-less-complicated terrestrial excursions? As a final point in this category: Why hasn’t the evidence substantially improved in line with the significant increase in both the quantity and quality of cameras? Yes, I’m sure Frank and I aren’t the only ones talking about these points, but it’s pretty rare to see them mentioned.

Obviously the third category, things I was previously unfamiliar with, is the most interesting. It turns out that the idea of “flying saucers” came from erroneous reporting attached to one of the very first UFO sightings. The pilot who made this observation actually said he saw “a flying craft shaped like a crescent with ‘wings’ that swept back in an arc”. This description got garbled by the AP and all subsequent reports described them as saucers. And wouldn’t you know it, the explosion of reports which followed the initial report also universally mentioned seeing saucers. This strongly suggest that the sightings were many a product of the reporting rather than actual UFOs of a specific type.

Of course all of the more recent excitement is based on videos recorded by Navy pilots which were released to the public in 2019. One of the most impressive of these videos is called the “GOFAST” video. Well it turns out:

When the NASA panel held its first public meeting in the summer of 2023, they reported an analysis of one of the three famous Navy UAP videos. Using some basic methods in geometry, they determined that the object seemingly skimming rapidly above water in the GOFAST video was actually at 13,000 feet and was moving at about forty miles per hour (which was the wind speed at the time).

Of course that didn’t shut things down, and now we have de-debunkings and even de-de-debunkings. I continue to be skeptical, but like Frank, I’m glad that the government released the videos so that people can examine them and do things like de-de-debunkings. Obviously the profusion of information and various commentaries on that information has not lessened conspiratorial thinking as much as we would have hoped, but that’s a topic for a different time.

I’ve started adding voice-overs to all of the posts. If you prefer those there’s actually a podcast feed with audio of all my posts, past and present. I use an AI clone of my voice to generate them. If anyone listens to the voice-overs I’d be curious what you think. For extra credit you can compare it to a podcast episode that I actually recorded.

Those words aren’t in the book, I looked them up. They are the study of ants and bees respectively, which is what he’s doing, but he knows you don’t use words like that if you want to be read. A lesson I’ve yet to absorb.

"For example, he argues that if you underestimate the risk of something you should do less of it, and if you overestimate the risk you should do more of it."

What if you overestimate the risk to be -1000 util when it's really -10 util? Still comes out to less than zero, even though it's an opportunity to improve your estimation.

I think that "everyone is the hero of their own story" is probably just one of those things that got subtly incorporated into popular writing at around the same time, see here: https://quoteinvestigator.com/2014/02/16/life-hero/

Personally, I think that the quote is a child (or grandchild?) or Proverbs 21:2, although the verse speaks of 'heroism' as in moral rectitude, not in the sense of being a protagonist.