Bad Therapy vs. Resilience

My submission to the Astral Codex Ten Book Review Contest. It was not a finalist. Comments are appreciated. (Especially ones pointing out how much better it is than the actual finalists.)

This is a long one. If you’d like to listen to it, you can do so here.

A child ruminating on all the bad things that have ever happened to him. Under the probing of a well-meaning, but ultimately misguided pseudo-therapist.

III- The Realm of the Potentially Traumatic

IV- “Won’t Somebody Please Think of the Children!?”

V- A Continuum of Parenting, With Sundry Bad Examples, and an Appearance by The Last Psychiatrist

I- Prologue

Years ago, I volunteered to accompany my son to a weeklong Boy Scout camp. It was an afternoon near the middle of our stay when an incredibly fast-moving thunderstorm arrived. I had gone to take a much-needed shower. When I entered the bathhouse the sky was clear and sunny, but by the time I was done the camp was engulfed in a tempest of rain and lightning. I waited out the worst of it before emerging to check on our camp. Everything was drenched, and the A-frame, where we also kept much of our gear, had collected a giant pool of water in one corner. I was attempting to deal with it all when a scout stumbled into camp sobbing. One of the other boys had been struck by lightning.

I raced to the spot to find a group of people all standing around in a circle. The boy was lying on the ground, motionless, his face a greenish-gray. The Assistant Scoutmaster, who happened to be an ER nurse, was desperately trying to revive him.

As I stood there helpless, I pictured my son there instead. The horror of that brief vision overwhelmed me.

The boy died. The staff and the scoutmaster did everything they could, but it was too late. I briefly experienced the pain of his parents, and it was crushing. In addition to the grief of his family, there would be friends, teachers, and acquaintances all impacted by his tragic and unexpected death.

Even though the week was only half over, we packed up and headed home. A few days later the funeral was held. All of the camp leadership drove down for it. While there they made it known to the parents that if any of the boys wanted to come back and re-do the weeklong camp, they would take care of everything: supervising the boys, preparing meals, providing tents and equipment, etc.

II- The Core Observation

At the time I was offered this choice, the decision to send my son back to the camp seemed obvious. You might even call it the default option. And, in fact, that’s precisely what my wife and I did.

It’s been a little over a decade since this happened, but in that time the default has changed: something of this magnitude—particularly involving the death of a child—would be treated as horrible, debilitating trauma. Or so Abigail Shrier argues in her recent book Bad Therapy: Why the Kids Aren't Growing Up.

Shrier is a polarizing figure. Her first book, Irreversible Damage: The Transgender Craze Seducing Our Daughters was, unsurprisingly, very controversial. Given this, whatever Shrier chose to write next would already have a certain amount of controversy baked in.

Bad Therapy doesn’t disappoint. In fact, it has already attracted even more controversy—as well as its share of plaudits. As such, it’s entirely possible that you have already formed an opinion on this book and its topic.

Whatever your opinion, favorable or not, the subject of trauma, therapy, and tots is much more complicated than it appears, some of this complexity is well-covered by Shrier, some of it is not, thus this review.

We need to begin with one very important observation, something that cannot be overlooked in this discussion by either Shrier or her critics:

Despite a vast increase in preventative resources, American mental health has not gotten any better, and by many measures it has gotten worse.

Shrier lays out the following statistics:

Between 1946 and 1960, membership in the American Psychological Association quadrupled.1 Then, from 1970 to 1995, the number of mental health professionals quadrupled again.2 In the United States since 1986, nearly every decade has seen a doubling of expenditure on mental health over the one before.3

…And yet as treatments for anxiety and depression have become more sophisticated and more readily available, adolescent anxiety and depression have ballooned.

I’m not the only one to have found something fishy in the fact that more treatment has not resulted in less depression. A group of academic researchers recently noticed the same. They published a peer-reviewed paper titled “More Treatment but No Less Depression: The Treatment-Prevalence Paradox.”4 The authors note that treatment for major depression has become much more widely available (and, in their view, improved) since the 1980s worldwide. And yet in not a single Western country has this treatment made a dent in the incidence of major depressive disorder. Many countries saw an increase.

The increased availability of effective treatments should shorten depressive episodes, reduce relapses, and curtail recurrences. Combined, these treatment advances unequivocally should result in lower point-prevalence estimates of depression,” they write. “Have these reductions occurred? The empirical answer clearly is NO.”5

I checked with several of the paper’s authors. Two confirmed that the same might be said for anxiety. As treatment has become more widely available and dispersed, point-prevalence rates should go down.6 They have not. And while the authors admit that there was likely more depression in the past than we realized, they argue that there is at least as much, and probably more, depression now.7 [Emphasis mine.]

Why is this? We don’t see this happening with other diseases. Dedicating additional resources towards cancer and heart disease, for example, has improved outcomes, not worsened them.

Why is mental health so resistant to improvement? Shrier believes it’s because these resources have been misallocated, the methodologies employed by these additional resources are misguided, and in too many cases they're actively harmful.

Put simply: we’re doing it wrong. The way in which we’re doing it wrong, however, is more complicated, and there are nuances and implications that even Shrier doesn’t completely grapple with, but in part that’s what I intend to do.

III- The Realm of the Potentially Traumatic

Given its prominent place in the title one would expect that therapy would occupy an equally prominent place in the book. It does, but therapy can mean different things to different people; it operates on a continuum.

On one end, there are people who believe that the word “therapy” should only be applied to the standards and practices of licensed therapists with many years of education.

On the other, we have the concept of “therapeutic culture”—the claim that therapeutic concepts have spread throughout society to the point that they are now ubiquitous. As a consequence of this, we are surrounded by pseudo-therapists: people who have (knowingly or not) adopted the role of therapists despite having received minimal, if any, training. The claims made by Schrier’s book mostly flow out of this latter definition of therapy. If the book had been titled Bad Pseudo-Therapy then I think she would have ended up with fewer complaints. (But probably sold fewer books, too.)

Nevertheless, a very interesting framework can be distilled from the book, one which gets to the heart of the many dilemmas posed by modern child-rearing.

To return to the example of my son, his mother and I could have treated the death of his fellow scout as a potentially traumatic event and sent him to a therapist. Perhaps, together, they would have decided it was no big deal. Or they may have discovered that my son was shaken up by things and they would have worked through it. It’s also not out of the realm of possibility that he could have ended up with a bad therapist. Certainly every profession has better or worse practitioners, also you don’t quadruple the number of people doing something in a short amount of time (see the excerpt above) without a drop in overall quality. While this latter scenario is part of Shrier’s argument, it isn’t the main thrust. Shrier is more concerned with the many pseudo-therapists we have created—teachers, nurses, guidance counselors, and even parents, all of them eager to (over)diagnose trauma and offer “comfort”.

If this had happened today, one of these pseudo-therapists might very well decide my son had suffered horrible trauma—perhaps some medical professional other than a therapist, perhaps we as his parents, or most likely someone at his school. From this “diagnosis” would flow all sorts of downstream effects—he certainly shouldn’t return to the camp—but there would be questions, and he would be labeled, talked to, and encouraged to engage in deep introspection.

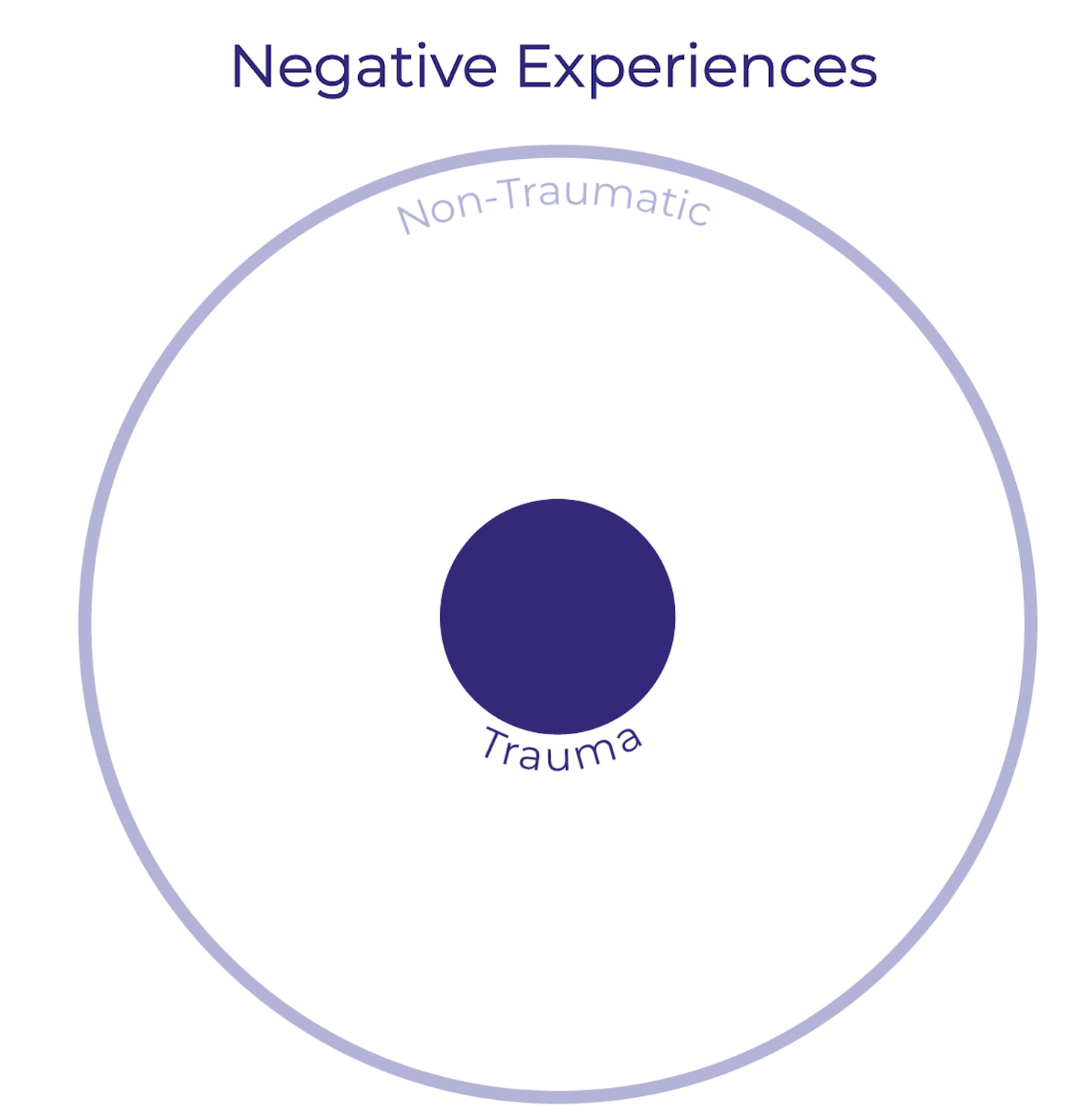

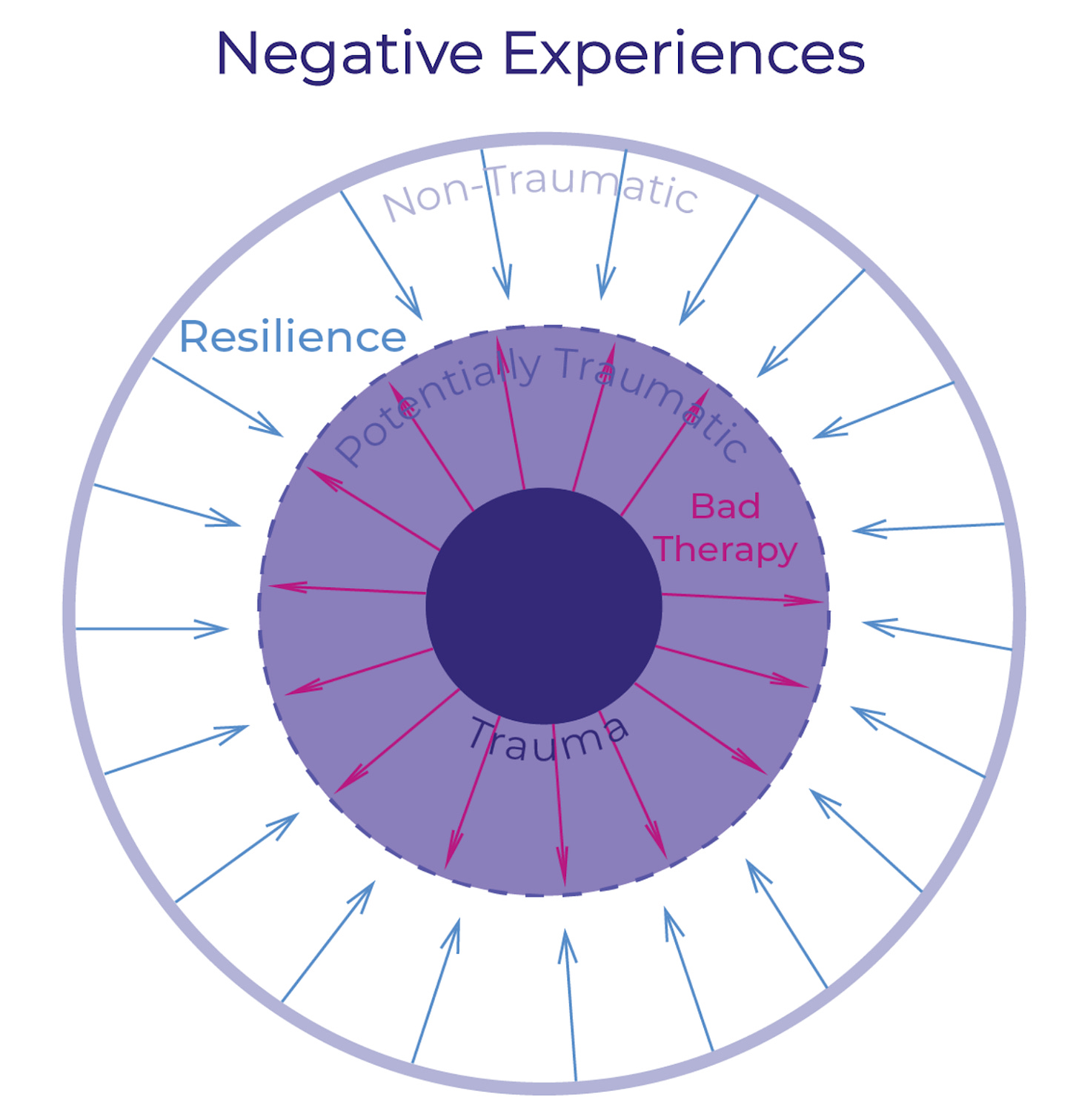

Before we get into the nitty-gritty, let’s establish a more general framework. Imagine the space of all the negative experiences a person might have.

Now, imagine that at the center of that space are the traumatic negative experiences, the ones so bad they almost certainly cause lasting trauma: things like sexual abuse spanning years, being kidnapped by strangers, or accidentally backing up over your child and killing them.

On the opposite side of things, at the very edge of our space of negative experiences, you have those events that are definitely non-traumatic. These are still negative experiences, but (almost) no one would claim that they had caused lasting trauma: Stubbing a toe, getting a cold, making a minor mistake. If we were to illustrate this space, it would look something like this:

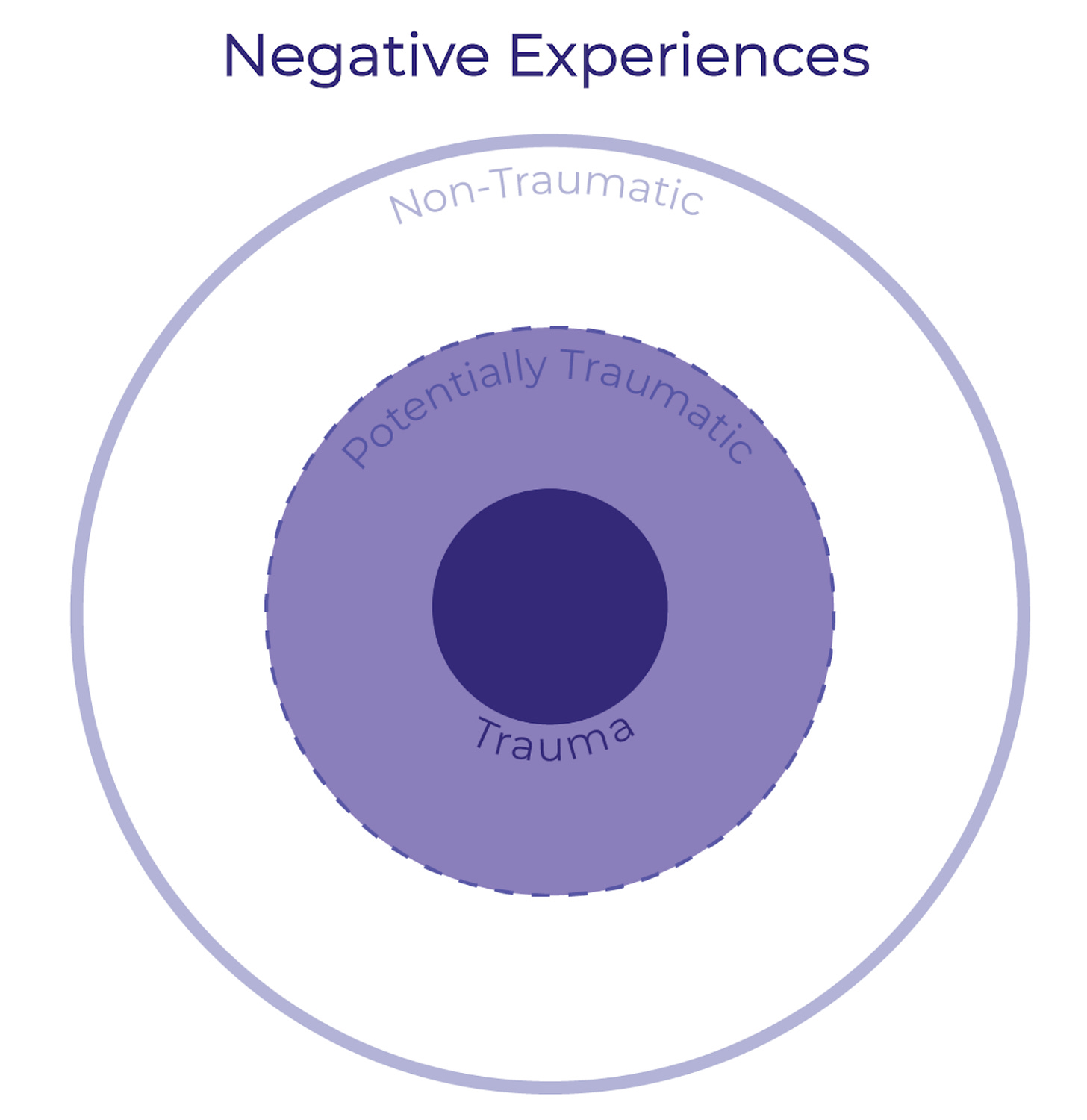

Thus far presumably everyone agrees with this structure. Some negative experiences are definitely traumatic, others are definitely not. The question is: what about the space between these two extremes—between the definitely traumatic and the decidedly non-traumatic? Things like: watching a terrifying movie when you’re too young; being repeatedly bullied in school; or watching someone in your scout troop die from a lightning strike.

This is the territory that Shrier focuses on, and it’s the space where most of the confusion and pseudo-therapy lies. Let’s call this zone “potentially traumatic”.

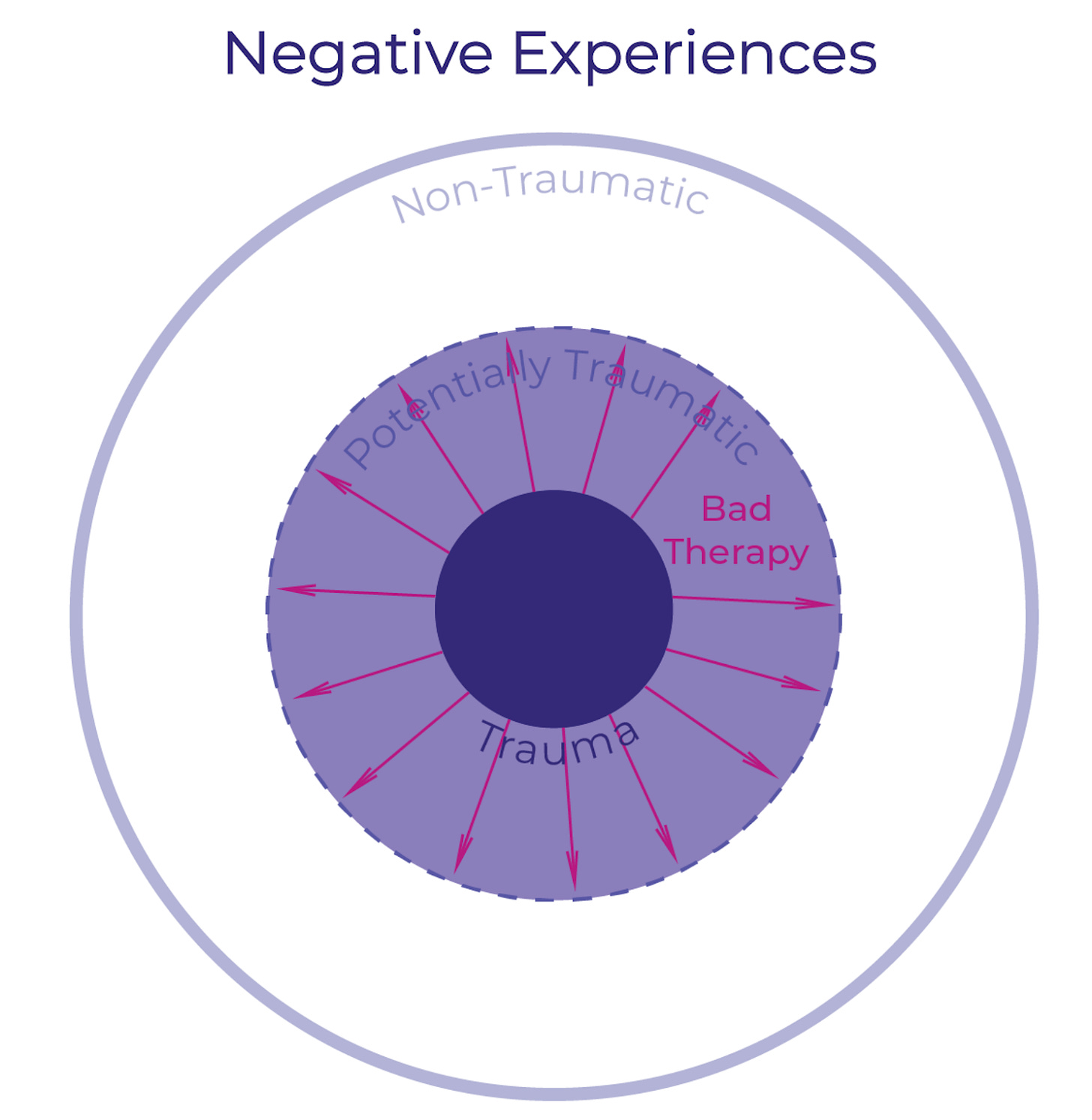

This zone is composed of negative experiences which might be traumatic depending on the person, their previous experiences, and—most importantly for our purposes—how the negative experience is dealt with or treated. This is where the majority of our focus is going to be, and though she doesn’t lay it out as specifically as I have, this is the realm Shrier is concerned about. She provides numerous examples of situations and experiences that only become traumatic through misguided interventions. She doesn’t deny that some negative experiences definitely cause trauma, and that this trauma benefits from competent therapy.8 Her book isn’t against all therapy; it’s against bad therapy, and the way we recognize it as bad is that rather than treating actual trauma it expands the definition and scope of trauma such that a greater number of negative experiences go from being potentially traumatic to definitely traumatic:

To return once again to the example of my son, I’m positive that if he had been subject to the sorts of practices Shrier describes that he could have been made to view his experience at scout camp as trauma—something that stayed with and haunted him, lessening his happiness and making him fearful. I’m confident that one of the many pseudo-therapists Shrier describes could have “talked him into this state”. I’m certain that I could have talked him into it, nor would it have involved any malice or double-dealing. It mostly would have been repeated variations of the question: “Are you sure you’re okay?”

Whereas by just assuming that he would “get back on the horse” my son grew up to love the outdoors and scouting. He earned his Eagle Scout, rose through the ranks in the Order of the Arrow, and eventually became the course director for a youth leadership training camp. Obviously this is just one anecdote, but my son’s story matches many of the “no therapy” arcs Shrier describes in her book.

So what are these practices of bad therapy Shrier describes?

IV- “Won’t Somebody PLEASE Think of the Children!?”

The debate over the declining mental health of children (particularly teenagers) has been raging at least since 2015 when Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff published their article The Coddling of the American Mind in The Atlantic (later turned into a book of the same name). Recently, it seems to have reached something of a crescendo with Haidt’s latest book The Anxious Generation. Everyone seems to basically agree that American adolescent mental health has gotten a lot worse; people just disagree about its cause.

Shrier adds her take with this book, and while there are many areas of overlap with Haidt, she points out that the trend started much earlier:

Instead, adolescent mental health has been in steady decline since the 1950s.9 Between 1990 and 2007 (before any teens had smartphones), the number of mentally ill children rose thirty-five-fold.10 And while overdiagnosis or the expansion of definitions of mental illness may partially account for this rapid change, it is hard to dismiss or contextualize away the startling rise in teen suicide: “Between 1950 and 1988, the proportion of adolescents aged between fifteen and nineteen who killed themselves quadrupled,” The New Yorker reported.11 Mental illness became the leading cause of disability in children. [Emphasis mine]

From Shrier’s perspective, while smartphones and social media are definitely very bad, they aren’t the primary cause of the problem, rather they acted as powerful accelerants for a misaligned therapeutic culture which already existed. How is it misaligned? Let’s look at some examples:

“Harmless” questions

Shier opens the book by recounting a recent trip with her son to the urgent care clinic. Once the immediate problem (a stomach ache) had been dealt with, a nurse arrived and asked if he could have a few minutes alone in order to do a “mental health screening” with her son. Shrier asked to see the screening questions. What she saw:

1- In the past few weeks, have you wished you were dead?

2- In the past few weeks, have you felt that you or your family would be better off if you were dead?

3- In the past week, have you been having thoughts about killing yourself?

4- Have you ever tried to kill yourself? If yes, how? When?

5- Are you having thoughts of killing yourself right now? If yes, please describe.12

Again, this was a visit to a pediatrician about a stomach ache. The nurse wasn’t a trained therapist, nor was Shrier or her son seeking any sort of therapy. .

This is precisely what I mean when I say that bad therapy takes potential trauma, e.g. sometime in the past few weeks, perhaps the child had some negative thoughts (”have you wished you were dead?” is a very broad question) and works to turn it into actual trauma.

First by labeling it as such: “Clearly this child needs help! Bad things are happening and we need to marshal the full resources of the state to make sure they’re okay!” Then by further treating it as trauma over the coming weeks (and possibly months and years).

What happens if the child answers “yes” to any of the questions? Particularly with no parent around to offer context or a different perspective. What cascade of interventions will that trigger? What labels will be applied? Will the parent have any say in them? Is that why the nurse wants to get the parent out of the room as soon as possible?

This is not the only occasion or venue where children will be asked questions like these. As long as we’re still thinking about the negative impact of phones, several companies have released mental health apps for kids. Shrier tried several:

Here are six of the first ten questions my therapist-bot asked me

“How lonely do you feel?”

“How supported do you feel?”

“How worried do you feel right now?”

“How down do you feel right now?”

“How often do you feel left out?”

“How sad do you feel right now?”

In each case, the question is searching for potential trauma and gearing up to turn it into actual trauma. This is also the equivalent to what I mentioned above, asking my son over and over again if he’s okay. It’s important to remember how suggestible kids are. Not to go on too much of a tangent, but recall that in the 80s just by asking kids over and over again if they had been abused authorities were able to construct an entire ritual satanic sex abuse ring. Yes, we’re just asking children if they’re okay, but at some point if you ask someone this question enough they’re forced to conclude the only reason you’re asking so much is that they’re not okay.

Identification, Rumination, or Marination?

Of all therapeutic methodologies, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) seems to have one of the best reputations. The most import steps in CBT are:

Identification of negative thoughts.

Once identified they should be evaluated: are these thoughts actually accurate and helpful?

Other therapeutic practices offer similar advice. It would appear from the many examples given in the book that—as is so often the case when something is scaled up—the nuance of this two-step approach has been lost especially when these practices and approaches have seeped into the broader culture.

We have ended up in a situation where there’s an enormous focus placed on the first step and almost none on the second step.

Negative experiences are relentlessly mined for potential trauma, and this excessive focus has transformed it from recognition into rumination. As if this were not bad enough, in far too many cases rumination has been supplanted by marination. Children are metaphorically immersed in their trauma, until it comes to define them. Pseudo-therapists double (or triple) down on identification, but it almost never proceeds past that point to the stage of evaluation.

Asking children to tap into their inner states and emotions is a necessary part of therapy; doing so incessantly is where things all too frequently go from treating trauma to evoking it. And this assumes that they need therapy in the first place, which is by no means certain! Ubiquitous therapy is bad therapy. This would almost appear to be self-evident, but Shrier also buttresses it by consulting with various experts:

Yulia Chentsova Dutton heads the Culture and Emotions Lab at Georgetown University… [and she asserts] “Emotions are highly reactive to our attention to them. Certain kinds of attention to emotions, focus on emotions, can increase emotional distress. And I’m worried that when we try to help our young adults, help our children, what we do is throw oil into the fire...We are basically telling them that this deeply imperfect signal”—that is, what they are feeling—“is always valid, is always important to track, pay attention, and then use to guide your behavior, use it to guide how you act in a situation.”

...It troubles Chentsova Dutton that so much therapeutic intervention with kids proceeds from the conceit that children should attribute great import to their feelings. How will she ever be a good friend if her own feelings are always, at every instant, front and center? How will she ever hope to function at work?

This gets back to the idea of suggestibility as well, the deeper children are pushed to ruminate on their emotions and their potential negativity, the more those emotions will become negative. It can easily become a feedback loop: constant encouragement to search for negative emotions leads to digging up any that might exist (and suggestibly creating some that don’t) which leads to rumination on these emotions (further reifying and emphasizing them) which leads to marinating in negativity…

Social-Emotional Learning

This approach has crystallized into what might be called a meta-curriculum: social-emotional learning.

This methodology combines the ubiquity already mentioned...

Sometimes described by enthusiasts as “a way of life,”13 social-emotional learning is the curricular juggernaut that devours billions in education spending each year and upward of 8 percent of teacher time.14 (Many teachers say they try to ensure that social-emotional learning happens all day long.)15 Through prompts and exercises, social-emotional learning (SEL) pushes kids toward a series of personal reflections, aimed at teaching them “self-awareness,” “social awareness,” “relationship skills,” “self-management,” and “responsible decision-making.”16 [Emphasis mine]

and the marination…

Social-emotional exercises typically invite kids to marinate in a time when they were sad, scared, or vulnerable. One of the most popular social-emotional curricula, Second Step, for instance, instructs eighth graders to divulge the following:

“Have you ever stayed overnight in the hospital?”

“Has someone close to you died?”

“Have you ever lost a championship game or important competition?”

“Do you attend religious services?”

“Have you ever worried about the safety of a loved one?”

with yet one more pseudo-therapeutic aspect—doing it while part of a group:

Ever since her school adopted social-emotional learning in 2021, Ms. Julie17 routinely began the day by directing her Salt Lake City fifth graders to sit in one of the plastic chairs she’d arranged in a circle. How is each of you feeling this morning? she would ask, performing a more intensive version of the “emotions check-in.” One day, she cut to the chase: What is something that is making you really sad right now?

When it was his turn to speak, one boy began mumbling about his father’s new girlfriend. Then things fell apart. “All of a sudden, he just started bawling. And he was like, ‘I think that my dad hates me. And he yells at me all the time,’ ” said Laura, a mom of one of the other students.

Another girl announced her parents had divorced and burst into tears.

Another said she was worried about the man her mother was dating.

Within minutes, half of the kids were sobbing. It was time for the math lesson; no one wanted to do it. It was just so sad, thinking that the boy’s dad hated him. What if their dads hated them, too?

Note that, in addition to all the pseudo-therapeutic aspects, all of these examples are focused on drawing out potentially traumatic events from the general space of all negative experiences. Once drawn out they have an increased potential to become actual trauma. Were all the sobbing children traumatized by these events? Certainly not. But might some of them have been? That certainly seems possible, particularly if this exercise is repeated every single day.

Had my son been subject to this gauntlet at the time of his experience at scout camp I have very little doubt that experience would have been turned into something debilitating and distressing, which may well have haunted him for years afterwards.

Why?

As a brief coda to all of this, it’s natural to ask why things have gone in this direction. Why is there so much pseudo-therapy in schools?18 As is the case with so many things, I think it proceeds from the best of intentions. Very few things are worse than suffering children, and anything which holds the promise of reducing that suffering would seem to be obviously good.

Unfortunately everything comes with second order effects, frequently negative, which can take a long time to manifest and are difficult to detect even then. Because of this there seemed to be very little downside to this vast expansion in therapeutic practices, and minimal harm if they weren’t done quite right. Unfortunately this has not been the case, there have been negative effects, and such negative effects are common in medicine. Treatments which are life saving for the desperately ill, can, somewhat paradoxically, result in significant harm if applied to those who are basically healthy. In medicine the formal term for this is iatrogenesis: harm caused by medical treatment. Shrier makes it one of the pillars of her book. Shrier offers up this startling list of iatrogenic counseling:

Police officers who responded to a plane crash and then underwent debriefing sessions exhibited more disaster-related hyperarousal symptoms eighteen months later than those who did not receive the treatment.19 Burn victims exhibited more anxiety after therapy than those left untreated.20 Breast cancer patients have left peer support groups feeling worse about their condition than those who opted out.21 And counseling sessions for normal bereavement often make it harder, not easier, for mourners to recover from loss.22 Some people who say they “just don’t want to talk about it” know better than the experts what will help them: spending time with family; exercising; putting one foot in front of the other; gradually adjusting to the loss.23

If you want to dig deeper into therapeutic iatrogenesis then the book is an excellent resource, but my goal is to establish a continuum, speaking of which:

V- A Continuum of Parenting, With Sundry Bad Examples, and an Appearance by The Last Psychiatrist

I hope these stories of therapy culture are illuminating; I'll admit that I also find many of them to be amusing. But, of course, these things all happened and similar things are happening all the time. At some point it becomes worrisome rather than humorous.

i) Shrier opens one chapter with a story about her daughter:

The first time anyone suggested my then seven-year-old daughter had “a lot of anxiety,” I was not at the pediatrician, but at a parent-teacher conference. “She’s looking at the clock a lot at the end of the day,” the assistant teacher piped up. “She seems to have a lot of anxiety about missing the bus. We thought you should know.”

If that’s what these pseudo-therapists are identifying as anxiety then no wonder all of the kids are anxious. “Missing the bus” that’s a good one. Try “when is another boring day of school going to end so I can get out of here?” Also, is it just me, or is there an assumption that she must be anxious because there’s no possibility that she could be bored by what the teachers are doing?

ii) She also includes stories about the complete helplessness of children:

David offers me [a] recent [example] to prove his point. At his students’ first concert of the year, a succession of boys approached him with their clip-on ties in hand, unsure how to fasten them. They weren’t asking how to tie a Windsor knot, he wanted me to know. They wanted him to affix their clip-on ties. “One of the moms looked at me. She’d seen me doing this all day long, and she’s just like, ‘These kids are helpless.’ They’re literally fifteen and sixteen years old. And it’s like you’re dealing with an eight- or nine-year-old.”

This complete avoidance of even mildly difficult things would appear to be an outgrowth of parents' desire to avoid any potential trauma altogether.

iii) This mother takes things to a level that’s almost bizarre:

As an example, Beth recalled that one college co-ed brought her mom along to the appointment. The mom kept track of her daughter’s menstrual periods with an app on her phone.

iv) One of the sections of the book is titled “Battered Mommy Syndrome”. The irony is strong here. Parents who desperately want their kid to be non-violent end up with kids who have violent impulses… towards them.

A young, well-heeled mother was struggling with a recalcitrant six-year-old son. “Please be a good boy,” the woman had said to her son. “If you’re good for just five minutes, when we get home, I’ll let you do anything you want. What do you want?”

The little boy looked his mother straight in the eye. “I want to punch you in the face,” he said.

One could go pretty deep down the rabbit hole psychoanalyzing this. But it sure feels like subconsciously the child wants to see the parent exercise some level of authority. And punching them in the face seems like a last ditch attempt to evoke that.

v) More battering, but the idea that there’s a Slate Parenting group on Facebook is endlessly amusing. It’s one of those times where a group parodies itself better than its critics ever could.

If someone wanted to kill all human desire to reproduce—to achieve, at last, this thing environmentalists call “population control”—steering readers to the Slate Parenting Facebook group might be a promising way to start.

Home to an educated, conscientious, liberal-leaning readership of eighteen thousand regular members, the Slate Parenting Facebook group provides a worthy terrarium in which to observe highly educated, progressive, therapist-directed parents as they air dilemmas and seek advice from their equally flummoxed counterparts…

“Anyone have advice about how to get a three-year-old to accept the consequences?” writes Airin, one frustrated parent. “When he hits, kicks, or yells (no provocation), how do I get him to calm down? I’ve tried addressing his feelings and time-outs. But when he goes into time-out, he gets very destructive and violent (throwing anything he can lift) or attacks me if I’m there.”

vi) Finally there’s the book Raising Raffi by Keith Gessen.

Gessen is a Harvard-educated writer and editor who tears his hair out for over two hundred pages, while consulting every possible book on how to coax his toddler, Raffi, to behave.

Once—just once—when Raffi is attempting to wrench the head off his newborn brother, ignoring Gessen’s command to stop, Gessen gives the boy’s hand a smack. This launches Gessen into a maelstrom of guilt and self-doubt. The clever boy runs straight to Mom, who leaps to Raffi’s defense and demands to know if Gessen in fact hit their son.

“Dada’s not nice,” the little boy declares.

“The words cut me to the quick,” Gessen writes. “If there was one thing I aspired to be, it was nice. I wanted to be nice. I wanted my son to feel that I was a warm presence in his life.”

It would be nice if parents were more immune to the pervasive pseudo-therapy currently running rampant, but, as illustrated by these examples, in so many cases they’re not. Many parents in fact have gone beyond identifying negative experiences to trying to stop them all together. Which takes us to:

The Last Psychiatrist and the Problem of Discontinuity

Reading these examples triggered a memory of a long-ago blog by The Last Psychiatrist (TLP). For those unfamiliar with his work, he blogged between 2005 and 2014, before disappearing suddenly. He later re-emerged in 2021 with a book. (See Scott’s review here.)

The post in question was discussing the mistakes often made by parents who are psychiatrists, but now that every parent aspires to be a psychiatrist, or at least a therapist, this mistake is being made far more often, including by most of the parents I just mentioned:

SOME psychiatrists think/try to do something noble (criticize behavior and not the child itself) but they are HUMAN, and get tired. They will eventually get angry, and, from a kid's perspective, when the parent gets angry is what matters. What did I do to piss Dad off?

The opposite of this, call it the non-psychiatrist parent, is calm, then gets a little angry, a little more angry, a little more angry, then yells, screams. There's a build up. A few years of this and you realize that there are some things that make Dad a little angry, and other things that make him really angry. There's normal, varying levels of human emotion to different situations.

But the child of a psychiatrist doesn't get that. He gets binary emotional states. "Lying is not acceptable behavior." Later: "Yelling loudly is not acceptable behavior." Later: "Picking your nose is not acceptable behavior." Later: "Stealing is not acceptable behavior." What's the relative value? A kid has no idea-- he thinks the value is decided by Dad, not intrinsic to the behavior. "Eating cookies before dinner is not acceptable behavior." Later: "Kicking your brother is not acceptable behavior."

Ok, now here it comes:

After seven or eight or twenty five "not acceptable behavior" monotones, Dr. Dad can't take it anymore; he explodes. "Goddamn it! What the hell is the matter with you?! What are you doing?!!" All the anger and affect gets released, finally. The problem-- the exact problem-- is this: the explosion of anger came at something relatively trivial. Maybe the kid spilled the milk.

So now the four year old concludes that the worst thing he did all day was spilled the milk-- not kicking his brother, or lying, or stealing. Had he not spilled that milk, Dad wouldn't have gotten angry.

I imagine most people understand that this sort of radically inconsistent parenting is bad. But it’s important to recognize that it’s not just the explosion at the end that’s bad; to recognize that the answer is not to be calm all the time. And it’s not merely because it’s impossible (though it is). It’s because the calm, in the end, is just as bad. The explosion is misleading because it lays far too much emphasis on the spilled milk. The calm is bad because it doesn’t lay any emphasis on anything. Picking your nose provokes exactly the same response as stealing.

Gessen’s story with Raffi is a perfect illustration of this concept. Had there been some gradation in Reese’s approach then smacking the boy’s hand would fit comfortably at the top of a continuum of responses to bad behavior (which is where “attempting to wrench the head off his newborn brother” belongs). An argument can be had about whether “smacking” is ever appropriate, but if not then something else would be at the top of the continuum. Instead we end up in a situation where there’s no scale on which things can be placed and so smacking Raffi’s hand ends up being a horrible and unprecedented breach, something that is inevitably viewed as being completely beyond the pale, both by Raffi and his mother.

Creating gradation in this space:

…encompasses most if not all of what Shrier is saying. Instead we have replaced gradation with an effort to wrap everything up into a single overarching anti-trauma effort. A one-size-fits-all approach that first attempts to stop negative experiences from happening—voices are never raised, punishment is never arbitrary, hands are never smacked (see all the examples above). But, if a negative experience does slip through then the overwhelming effort they put towards avoiding negative experiences is now turned towards mitigating those experiences. They must be treated with all the care and seriousness a parent (or teacher) can muster. But again there is no gradation. In both cases it’s all or nothing. Parents and educators attempt to avoid all negative experiences but the moment one gets through their carefully crafted defenses it’s immediately considered to be traumatic. So how do we restore gradation?

VI- Resilience

A reminder of where we left off in Section III:

We’re seeing an ever-expanding circle of bad therapy which threatens to totalize all negative experiences as traumatic. The examples given above represent this impulse at its most extreme. There is an appealing simplicity to that approach which can be very attractive. Abandoning any sense of a continuum means that there are no difficult decisions about whether therapeutic intervention should be used. We can just use it all the time and everywhere. If there were no negative effects then that might actually work. But Shrier makes a compelling case that there are negative effects. The reason I started this review with my son’s own experience is that it bears this out. I think it would have been very easy to turn his experience into trauma.

So how do we find a happy medium?

How do we create a continuum where we treat negative experiences with the level of seriousness they deserve, and, ideally, no more and no less?

If you spend any time at all reading books about the various crises afflicting children you’ll come across the term resilience. It’s offered up everywhere as the one thing that will solve the various crises. But within these books advice on actually creating resilience is thin, and mostly consists of advice on what not to do. But the great thing about the framework we’ve extracted from Shrier’s book is that it naturally leads us to a definition and a methodology for creating resilience. It’s the quality that turns the potentially traumatic into the non-traumatic—resilience takes negative experiences and makes them normal. This is what turns the vast space between actual trauma on one side and the smallest bad event on the other into a continuum.

This leads to a more muscular view of resilience than that found in most of the discussions, and as such this is the area where Shrier has attracted the most criticism. For example see this quote from a review by Ozy Brennan:

But Abigail Shrier’s preferred alternative to Internet Mental Health Culture is what you might call Fifties Dad Mindset. She’s quite explicit about this: multiple times in Bad Therapy, she asks readers to adopt the behavior of their own parents and grandparents.

Or this excerpt from a review by Meghan Bell:

She suggests that all parents have to do is fire the therapist, use a little more authority, take away the smartphone, encourage kids to “knock it off, shake it off”, and everything will be okay. Tellingly, she titles the final section of her book, “Maybe There’s Nothing Wrong with Our Kids.”

I agree with much of the criticism in both reviews, and if you want a broader perspective (or a reason to dismiss the book) I urge you to read both of them. But still we need to return to the core observation we opened with: We have poured an exponentially increasing amount of resources into mental health. Much of it has gone into actual trauma, which is great, but a great deal has gone into turning potentially traumatic experiences into actually traumatic experiences.

In the end I’m just a parent, who wants to know how to raise healthy kids. And I can get a ton of advice and assistance on how to add more therapy-like activity into my kids life. What is in far shorter supply is advice and help on adding more resilience. Even Shrier's book, which strongly encourages resilience, gives out little in the way of practical advice—mostly retreading advice like not freaking out if your nine year old wants to walk to the bus alone. There is also some advice that amounts to “copy your parents”. And I agree that it can seem a little hand-wavy. That’s why the framework of gradation ends up being so useful.

The first comment on Ozy’s review points to the heart of the matter:

It feels to me like the world (at least the middle-class American world I live in) needs a bit more of this Shrier-type thinking, in the same way it needs a little more of the Jordan Peterson type of stuff. Just a smidge, not a whole serving.

I don’t know if I would say “just a smidge” but the commenter certainly hit on the key point.

How much should we be saying, “knock it off, shake it off”?

How much should we act like our parents?

What behaviors should we be copying?

And what behaviors should we make sure to leave behind?

Toughening kids up would seem to require exposing them to negative experiences so that they can learn to deal with them in a healthy fashion, how negative and what sorts of experiences? Is it enough to let negative experiences happen or should we be pushing some onto them? Given how many resources are being channeled in the other direction (all with the best of intentions) it seems like we probably need to push back a lot in the resilience direction. But what does that look like? I think the framework from the diagram is very useful in this regard, but it’s obviously not the whole story.

As is so often the case, history is both instructive and divisive. As an example of resilience Shrier offers up the story of her grandmother:

My maternal grandmother—the most optimistic, can-do woman I’ve known—entered the world a matricide. In 1927, her mother died giving birth to her, a fact two of her less forbearing older siblings rarely let her forget. For the first few years of her life, a series of indifferent cousins in DC and Philadelphia were called upon to nurse and house her. Never given enough milk, my grandmother’s teeth grew in gray. Scanty nutrition stunted her growth.

Her widowed father could not raise her, though stories varied as to why. Whispers followed her, in Yiddish, that a relative molested her while she lived in his home. Others claimed that her father—a Russian immigrant, bereft, undereducated and overwhelmed—simply liked the racetrack too much.

When my grandmother turned six, she had her first real stroke of good luck. Her eldest sister, Clayre…married Sammy, and they took my grandmother in and raised her.

When she was sixteen [my grandmother contracted] polio. [The doctor] ordered my grandmother into isolation at Gallinger Hospital.24 Clayre burned all of my grandmother’s clothes…

[M]y grandmother turned seventeen in an iron lung, straining to breathe and unable to swallow. Family visits were mimed through a hallway window: a wave, a smile, a blown kiss. The dreaded illness lasted a year until, one day, my grandmother’s tongue and pharynx enlivened enough to negotiate a teaspoon of water. Nurses crowded her bedside to witness her first sips.

If she mourned the loss of an entire year of high school, my grandmother never mentioned it…

She completed law school at night and became one of the first female judges in Maryland history.25 And until the last year of her life, at ninety-four, her sharp mind softened with age, she held fast to a feeling that would not leave her: every day alive was a miracle.

This is definitely resilience. Also we see a notable lack of potential trauma being turned into actual trauma. Of course up until very recently people encountered more than enough negative experiences to either make them resilient or break them entirely. That is no longer the case. Much of the reason for all of the behavior already documented in this review is that it finally seems possible to shield children from the sorts of tragedies experienced by Shrier’s grandmother; if that’s the case, why wouldn’t we? The review has already spent a lot of time answering that question, but the more specific reason is that they need to develop resilience. If we’re going to establish a healthy continuum of experiences we have to make a push for resilience. What does that mean? What does it look like?

Let’s take a very simple example: If my son absolutely did not want to return to camp should I have forced him to? If it would have been bad to engineer things in order to make the experience traumatic, is it good to engineer things to make it not traumatic?

We’re not talking about giving the kid polio and putting him in an iron lung to toughen him up. We’re just talking about forcing him to spend a week outdoors doing mildly difficult activities.

Back then the question never came up, but how would I deal with it now? How would other people want me to deal with it? I think most people would say, “Definitely not! Forcing him to go would be cruel.” But I’m not so sure. It’s an enormously difficult question. It seems clear that we can’t err on the side of treating all things that are potentially traumatic as actually traumatic, but where is the line? How do we know when a negative experience is a chance to exercise resilience or something that requires therapeutic intervention?

The big contribution of this book is to point out that a lot more things are a chance to exercise resilience and a lot fewer things should be referred to therapy, particularly pseudo-therapy of the kind that’s become ubiquitous.

When I consider the question of what children really can put up with, and have the experience be resilience-inducing rather than trauma creating, I’m reminded of an excerpt I read long ago on Slate Star Codex about an American child attending a private school in China:

During his first week at Soong Qing Ling, Rainey began complaining to his mom about eating eggs. This puzzled Lenora because as far as she knew, Rainey refused to eat eggs and never did so at home. But somehow he was eating them at school.

After much coaxing (three-year-olds aren’t especially articulate), Lenora discovered that Rainey was being force-fed eggs. By his telling, every day at school, Rainey’s teacher would pass hardboiled eggs to all students and order them to eat. When Rainey refused (as he always did), the teacher would grab the egg and shove it in his mouth. When Rainey spit the egg out (as he always did), the teacher would do the same thing. This cycle would repeat 3-5 times with louder yelling from the teacher each time until Rainey surrendered and ate the egg.

Outraged, Lenora stormed to the school the next day and approached the teacher in the morning as she dropped Rainey off. Lenora demanded to know if Rainey was telling the truth – was this teacher literally forcing food into her three-year-old son’s mouth and verbally berating him until he ate it. The teacher didn’t even bother looking at Lenora as she calmly explained that eggs are healthy and that it was important for children to eat them. When Lenora demanded she stop force-feeding her son, the teacher refused and walked away.

The punchline is that Lenora’s outrage turns to amazement:

After a few years in China, Rainey changed. Though Lenora constantly worried if Rainey’s creativity and leadership potential was being snuffed out, she couldn’t help but be impressed by his emerging self-control. He could sit still for longer. He always greeted people politely. He finished eating his food. He asked permission a lot.

Lenora didn’t realize what Rainey had become until she took him back to the US for a few weeks to visit family. There, the contrast between Rainey and his same-aged American counterparts become stark. Lenora’s friends’ kids ate junk food all day while Rainey asked for vegetables. They couldn’t read or do basic addition while Rainey was close to being bilingual and had started double-digit addition and subtraction by first grade. They wandered obliviously in their own worlds while Rainey’s Chinese grandparents were thrilled to receive respectful greetings every time Rainey entered the room […]

The point here is not to force-feed your kids eggs; but that children are a lot tougher than you think. When we do something like force a kid to go back to scout camp we’re a lot more likely to build resilience than we are to create trauma. Obviously taking any specific action is very dependent on the child in question but even then, probably less than we think.

This is not to say it’s an easy problem; I’m glad that I’m not currently grappling with the decision of whether to force my son to go back to camp. But, particularly in hindsight, if it had come to that at the time, I would have.

You may be looking back on this eight thousand word review and thinking, “That’s it? He just wanted to say that it’s difficult to balance comfort and coddling? We’ve known that for ages!” To a first approximation you’re completely correct. But also the reason people have been talking about it for ages is that it’s a really difficult problem. My hope is that the insights provided in this review will make it at least slightly easier.

I’m not sure if this is my longest post ever. I’m not aware of an easy way to see the word counts of everything that came before. But if it’s not it’s close. I appreciate you making it to the end. And if you have any comments I’d love to hear them.

In this case and all subsequent cases, when I quote from the book I will duplicate its footnotes:

In 1946, Congress passed the National Mental Health Act. Between 1946 and 1960, membership in the American Psychological Association ballooned from 4,173 to 18,215. Moskowitz, In Therapy We Trust, 154.

Furedi, Frank, Therapy Culture: Cultivating Vulnerability in an Uncertain Age (New York: Routledge, 2004), 10.

“Statista Research Department, “Total U.S. Expenditure for Mental Health Services 1986–2020,” 2023, Statista, www.statista.com/statistics/252393/total-us-expenditure-for-mental-health-services

Ormel, Johan, et al., “More Treatment but No Less Depression: The Treatment-Prevalence Paradox,” Clinical Psychology Review 91 (February 2022) 102111, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34959153.

Ormel et al., “More Treatment but No Less Depression.

See, for example, Ormel, Johan, and Michael VonKorff, “Reducing Common Mental Disorder Prevalence in Populations,” JAMA Psychiatry 78 no. 4 (April 2021): 359–60, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33112374.

It’s important to note that the authors looked at point prevalence, not lifetime prevalence. Point prevalence is the signal rate in this context. After all, if someone had had a depressive episode twenty years earlier, that would count in “lifetime prevalence” but not provide an accurate marker of whether the last twenty years of psychiatric gains had made a dent in rates of depression.

Therapy as treatment for trauma is not the only kind of therapy, but it’s the area Shrier spends all of her time on, so that’s where we’ll be focusing as well.

Between 1950 and 1988, the proportion of adolescents aged between fifteen and nineteen who killed themselves quadrupled,” The New Yorker reported. Andrew Solomon, “The Mystifying Rise of Child Suicide,” The New Yorker, April 4, 2022, www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/04/11/the-mystifying-rise-of-child-suicide.

Whitaker, Robert, Anatomy of an Epidemic: Magic Bullets, Psychiatric Drugs, and the Astonishing Rise of Mental Illness in America (New York: Crown, 2010), 8.

Whitaker, Anatomy of an Epidemic, 8.

Suicide Risk Screening Tool,” National Institute of Mental Health Toolkit, accessed August 6, 2023, https://www.nimh.nih.gov/sites/default/files/documents/research/research-conducted-at-nimh/asq-toolkit-materials/asq-tool/screening_tool_asq_nimh_toolkit.pdf.

As one school in Illinois put it: “SEL is more than a process, a methodology, a curriculum—it is a way of life.” “Social Emotional Learning,” Stevenson High School, accessed September 16, 2023, https://www.d125.org/about/sel.

$1.72 billion spent in social-emotional learning educational materials alone. “United States Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) Market Report 2022: Instructional Materials were $1.72 Billion, up 25.9% Y-o-Y and are Forecast to Increase at a Lower Rate in 2023-2024,” GlobeNewswire, November 17, 2022, www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2022/11/17/2557934/0/en/United-States-Social-and-Emotional-Learning-SEL-Market-Report-2022-Instructional-Materials-were-1-72-Billion-up-25-9-Y-o-Y-and-are-Forecast-to-Increase-at-a-Lower-Rate-in-2023-2024.html; Krachman, Sara Bartolino, et al., “Accounting for the Whole Child,” ASCD, February 1, 2018, https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/accounting-for-the-whole-child.

Langreo, Lauraine, “How Much Time Should Schools Spend on Social-Emotional Learning?,” Education Week, May 24, 2022, https://www.edweek.org/leadership/how-much-time-should-schools-spend-on-social-emotional-learning/2022/05.

“An important difference between SEL and character education is that some character education approaches are focused on developing morally responsible youth, and that is not the defining characteristic of SEL. It is important to make that distinction. Teaching morals and values can raise concerns about whether they can be changed, and whether instruction is the responsibility of families or schools.” Kim Gulbrandson, “Character Education and SEL: What You Should Know,” July 6, 2018, Committee for Children, www.cfchildren.org/blog/2018/07/character-education-and-sel-what-you-should-know.

Name changed to avoid embarrassing a teacher who was just doing precisely what her administrators directed.

And to be clear, it’s not all pseudo-therapy, while there's more than enough harm being caused by people with no licensing and very little training, there are also plenty of school psychologists, and I’ve seen no evidence that they act to mediate these practices, rather they seem to participate just as vigorously as those who haven’t been extensively trained.

Carlier, Ingrid V. E., et al., “Disaster-Related Post-Traumatic Stress in Police Officers: A Field Study of the Impact of Debriefing,” Stress Medicine 14, no. 3 (1998): 143–48, https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1700(199807)14:3<143::AID-SMI770>3.0.CO;2-S.

Berk, Michael, et al., “The Elephant on the Couch: Side-Effects of Psychotherapy,” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry (January 2009): 789, https://doi.org/10.1080/00048670903107559.

Helgeson, Vicki S., et al., “Education and Peer Discussion Group Interventions and Adjustment to Breast Cancer,” Archives of General Psychiatry 56, no. 4 (1999): 340–47, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/article-abstract/1152701.

Brody, Jane E., “Often, Time Beats Therapy for Treating Grief,” New York Times, January 27, 2004. See also Neimeyer, R.A., “Searching for the Meaning of Meaning: Grief Therapy and the Process of Reconstruction,” Death Studies 24, no. 6 (September 2000): 541–58, https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180050121480.

Bonanno, George A, The Other Side of Sadness: What the New Science of Bereavement Tells Us About Life After Loss (New York: Basic Books, 2009). See also Pinker, Susan, “Exercise Can Be the Best Antidepressant,” Wall Street Journal, March 23, 2023, www.wsj.com/articles/exercise-can-be-the-best-antidepressant-5101a538?mod=e2tw. (“New research finds that as little as 12 weeks of regular exercise can alleviate symptoms of depression as effectively as medication.”)

The hospital was renamed D.C. General Hospital in 1953. In 2001, it closed. See “Gallinger Municipal Hospital Psychopathic Ward,” Wikipedia, accessed September 17, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gallinger_Municipal_Hospital_Psychopathic_Ward.

Estrada, Louie, “Bess Lavine, Half of Mother-Daughter Judge Team, Dies at 94,” Washington Post, October 5, 2022, www.washingtonpost.com/obituaries/2022/10/05/bess-lavine-prince-georges-judge-dead.

Man, your starting anecdote of the kid who dies at camp is devastating. It’s amazing how we are both so fragile and so resilient.

Also, do you think the pendulum is swinging back on the coddling? I feel like young people of a particular age think everything is trauma related, but maybe it’s peaked.

No Way! I read this during the ACX review contest and was blown away by it. I then read the book and about 15 people in my family read it based on my recommendation. I haven't been to your blog for a few years, but I should have guessed that you were the reviewer.