Short Book Reviews: Volume IV

A weird grab-bag of Chesterton, evangelicalism, business, pulpy fantasy, education, and difficult conversations.

How to Have Impossible Conversations: A Very Practical Guide by: Peter Boghossian and James Lindsay

Book Yourself Solid: The Fastest, Easiest, and Most Reliable System for Getting More Clients Than You Can Handle Even if You Hate Marketing and Selling by: Michael Port

He Who Fights with Monsters: A LitRPG Adventure by: Shirtaloon

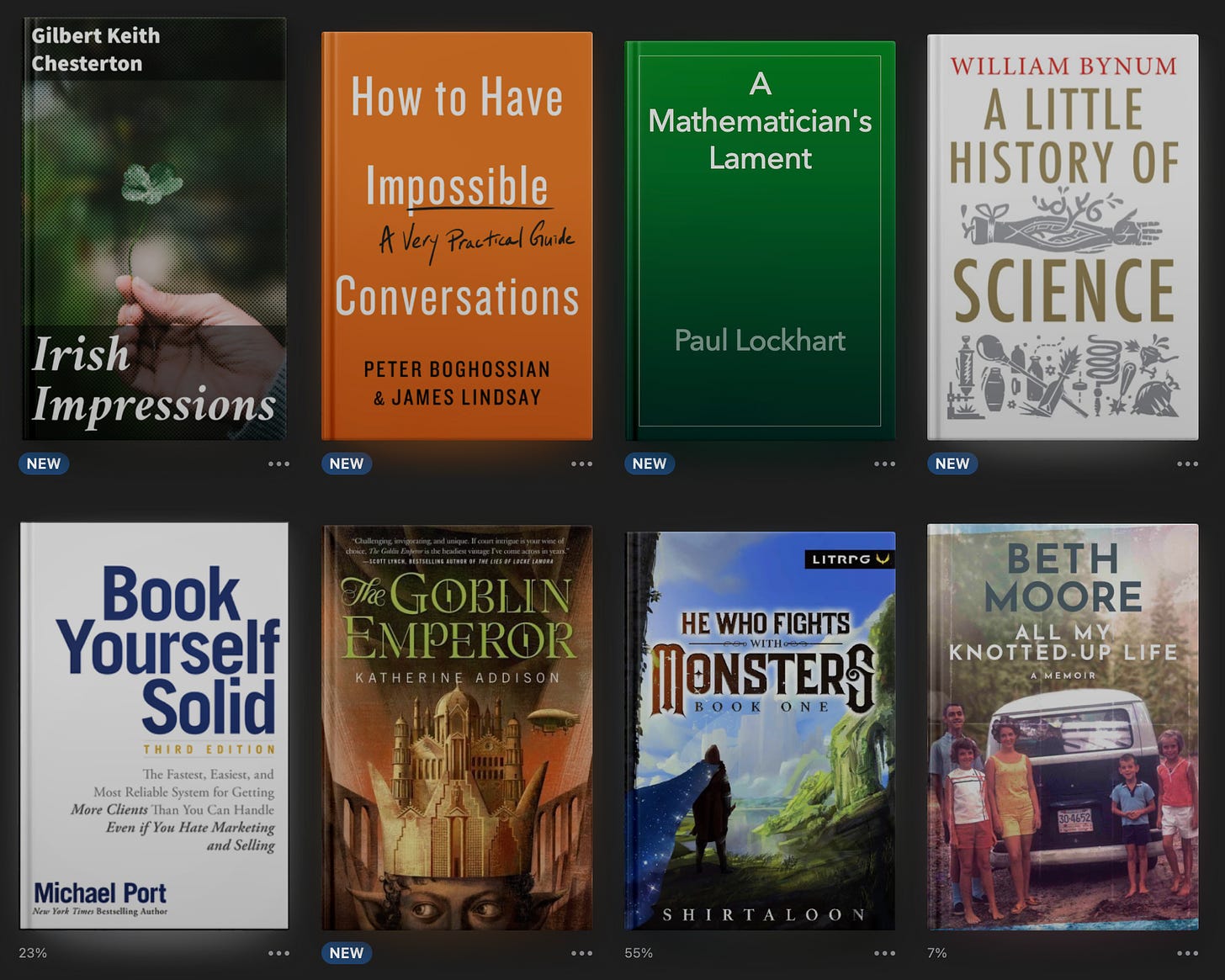

March was a pretty good month. I’m going to say that my mojo has largely returned. You may be wondering, if that’s the case, why was this so late, and when are we going to get something other than book reviews? Well, first off I did a lot of traveling. I attended both Gary Con (a celebration of the life of Gary Gygax, creator of Dungeons & Dragons) and a process theology conference dedicated to the work of Iain McGilchrist (see my extensive discussion of his book The Master and His Emissary).

Secondly I’m working on three different special projects. I expect that at least two of them will eventually be published here. The other one is a presentation I’m doing for a homeschool convention, and I’m not sure how well it will translate into a substack newsletter.

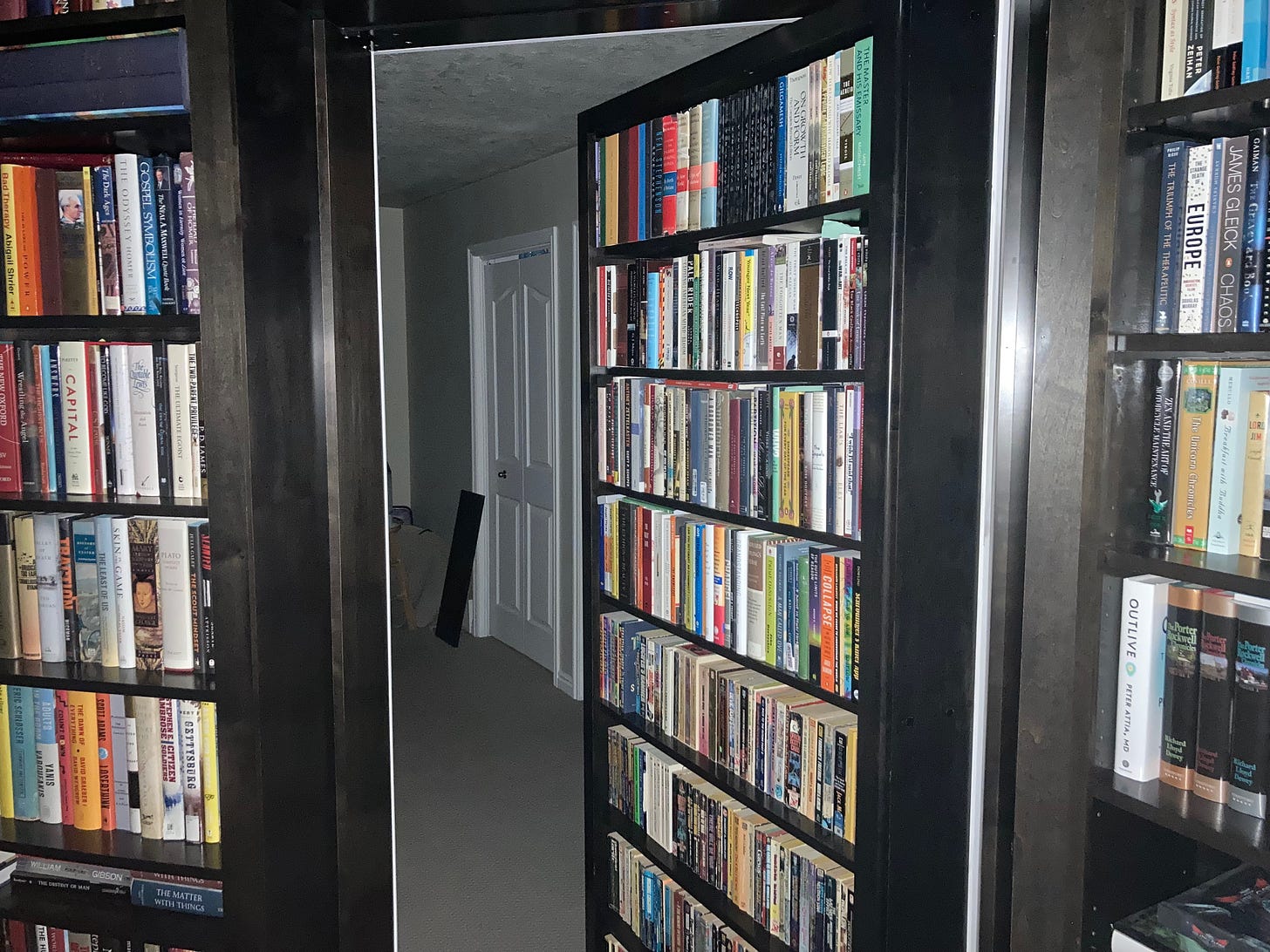

Finally I did an extensive remodel of the bedroom I was using for an office. Here’s how it looked before:

Here’s how it looks now:

Notice that I replaced the door with a Murphy door to maximize the shelf space. It’s super cool, but while it was being done I was something of a vagabond, which made it hard to focus. But it’s done. And I’m looking forward to getting down to work.

Non-Fiction Reviews

Irish Impressions

By: G. K. Chesterton

Published: 1919

84 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Chesterton’s sympathetic portrayal of the Irish published shortly after World War I had ended and just as the Home Rule crisis was about to transition into the Irish War of Independence.

What's the author's angle?

Religion plays a large role in this book, but what did you expect? Chesterton is going to be Chestertoning. Beyond that, he’s a Catholic writing for a largely Protestant audience in defense of Catholics.

Who should read this book?

Unless you’re really into Chesterton or this period of Irish history you can probably skip this one. That said, even when Chesterton is talking about something that would seem dated, he still manages to toss out some truly great lines. (Some of which I’ll include below.)

Specific thoughts: Chesterton’s a great writer regardless of the subject matter

I’m not completely unfamiliar with this period of Irish history, but my knowledge of it basically comes from what I managed to absorb on a trip to Ireland a couple of years ago. As such when Chesterton got too far into the minutia of 1919 I ended up feeling somewhat lost, but that happened less than I expected. Chesterton spends a lot of time connecting things to morality and religion. At the time it probably made the book tedious. A hundred years on it makes it timeless. Okay not the entire book, but certain passages to be sure.

I’ll get to those passages in a moment, but I did notice one surprising thing which I can’t let pass without a mention: Despite the fact that the Irish Potato Famine was closer to his time than World War II is to our time Chesterton never mentions it. I’m not entirely sure what to make of that...

And now a handful of quotes from the book which I particularly enjoyed:

There are ten thousand errors in this, beginning with the primary error of an oligarchy, of treating a man as a servant when he feels more like a small squire.

To my own taste, the present tendency of social reform would seem to consist of destroying all traces of the parents, in order to study the heredity of the children.

If you are really concerned about your relations, you have to be concerned about your poor relations.

The sense of family is like a dog and follows the family; the sense of oligarchy is like a cat and continues to haunt the house.

The whole trend of what has been regarded as liberal legislation in England, necessary or unnecessary, defensible and indefensible, has for good or evil been at the expense of the independence of the family, especially of the poor family.

I assured them in vain that I did not need to have Irish blood in my veins in order to object to having Irish blood on my hands.

I suspect that many names and announcements are printed in Gaelic, not because Irishmen can read them, but because Englishmen can’t.

If I had to sum up in a sentence the one fault really to be found with the Irish, I could do it simply enough. I should say it saddened me that I liked them all so much better than they liked each other.

[T]he Protestant generally says, “I am a good Protestant,” while the Catholic always says, “I am a bad Catholic.”

It was admirably expressed to me by Mr. Yeats, who is now champion of Catholic orthodoxy, in stating his preference for mediaeval Catholicism as compared with modern humanitarianism; “Men were thinking then about their own sins, and now they are always thinking about other people’s.”

How to Have Impossible Conversations: A Very Practical Guide

By: Peter Boghossian and James Lindsay

Published: 2019

272 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Techniques one might use to engage in fraught conversations about politics, religion, conspiracies, or any other subject that might seem impossible to discuss.

What's the author's angle?

I didn’t know who Boghossian or Lindsay were until I started writing this review, but apparently they’re fairly well known (more on that in a second). Restricting myself just to this book there’s definitely an atheist vibe, but mostly they seem to really be looking for better ways for people who disagree to engage.

Who should read this book?

In this day and age, this might be a book that everyone needs to read. Certainly I think the world would be a better place if everyone had read this book, which is not something I can say about many books.

Specific thoughts: The tactics seem sound, but do they work?

Some of the techniques described by this book were pretty basic, and, moreover, widely known, but there were other techniques that seemed genuinely innovative. One in particular was the idea of asking people on a scale from 1-10 how sure they were of something. If they said 10 (or 1) then they’re an idealogue, and there’s very little point in trying to sway their opinion, though you can still seek to understand it. For example by saying “Wow, a 10, how did you come to be so certain? It must have been something really amazing and powerful.”

If, on the other hand, they give a value other than 1 or 10 then you might ask them why they’re a 9 rather than a 10, what aspect of the belief are they still uncertain about? What evidence inclines them to doubt? Now it should go without saying that this sort of technique should only be used in a respectful fashion, not as some tool to bludgeon people with, but it nevertheless would appear to provide a useful opening for discussion, which if you’re lucky might actually lead to a change in opinion, perhaps even your own opinion.

But, as is so often the case, we need to ask how this worked for the authors themselves. Recently I started listening to the podcast Blocked and Reported with Katie Herzog and Jesse Singal. And I noticed that when they wanted to reference the heights of stupidity, they would toss out James Lindsay’s name. Being someone who only recently started listening to the podcast I had no idea who that was. It was only after I finished the book and was preparing to review it that I realized that this was the Lindsay they were talking about.

I can only speculate on the potential relationship between writing a book about being open-minded and disagreeing respectfully, and going from the moderate left all the way to the far right. Perhaps it worked too well? One wonders if anyone has taken the tactics from this book and tried them on Lindsay.

A Mathematician's Lament: How School Cheats Us Out of Our Most Fascinating and Imaginative Art Form

By: Paul Lockhart

Published: 2009

140 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The horrible way we’ve decided to teach math.

What's the author's angle?

Lockhart, as you can tell from the title, is a mathematician. It is entirely possible that he expects too much from everyone else with respect to math.

Who should read this book?

It’s a stretch to call this an actual book (for reference it’s three hours on audio). As such, telling people to read this book is not a big ask. I think that anyone involved in teaching period, but in particular teaching math should read this book.

Specific thoughts: Everybody is an artist about what they know best

It has been said that everyone is conservative about what they know best, but I think this book illustrates another truism, that everyone is an artist, or at least an art critic about what they know best. Which is to say at the highest level of any endeavor the differentiating factor is often aesthetics. So it is with math as well. As such, Lockhart’s most extreme pronouncements have been filtered through a very opinionated aesthetic lens. Nevertheless it is true that there is something deeply wrong with math education in this country.

On the traditional side we imagine that by putting children in touch with great ideas and great thinkers that they will naturally come to love a subject, as such it’s not necessary to cultivate a love of math, it will happen on its own.

The more progressive/modern approach imagines that we need to teach critical thinking and that once that is in place, the child will naturally use it to sift out experts and great thoughts on their own. In this framework math is a necessary tool towards the development of that thinking.

These are both broad characterizations which overlook a lot of nuance, and along those lines I will venture to say that Lockhart represents a different angle, fitting comfortably into an Egan-esque model. (I.e. the educational philosopher Keiran Egan, recently brought to prominence by friend of the blog, Brandon Hendrickson and his award-winning book review of Egan’s The Educated Mind.) Egan urges educators to focus more on the journey. This involves cultivation, but cultivation in the soil evolution and culture have already provided—metaphors, questions, experiments, and stories. Whether we can use this methodology to create math artists at the scale and the depth Lockhart imagines is another story, but I think we can get a lot closer than through either of the conventional methods.

A Little History of Science

By: William Bynum

Published: 2012

272 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

A high-level overview of scientific development from the beginning of recorded history up until the present day.

What's the author's angle?

This is part of the “Little History” series, and so the author’s motivation is very much in that vein (i.e. quick, high-level overviews that focus more on delivering facts than telling stories).

Who should read this book?

As an overview of the history of science it was quite good, if that sounds like the kind of thing you might enjoy, then this is the book for you.

Specific thoughts: At a certain point one has read enough general overviews

For a long time I gravitated towards books like this. Broad surveys of big topics which provide the 50,000 foot view of a subject. While I was reading this book I decided that perhaps I had had enough of such overviews. This is not to say that they’re not valuable, and that this one wasn’t great, more that you end up with diminishing returns. When you first read a historical overview, it’s mostly filled with things you don’t know. As you continue to read them, you encounter more and more duplication; things which you already learned in a previous overview. I may finally be at the point where overviews no longer have anything to offer, or I guess more accurately that the ROI is no longer positive. I’m not sure what this means. I imagine it means that I have finally reached the point I should have been at when I graduated from college perhaps?

To be clear, this was a great and interesting survey of the history of science, and I would recommend it to anyone who feels that such an overview would be valuable.

Book Yourself Solid: The Fastest, Easiest, and Most Reliable System for Getting More Clients Than You Can Handle Even if You Hate Marketing and Selling

By: Michael Port

Published: 2006

336 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Numerous exercises a business owner can engage in to develop the practices necessarily to attract more business.

What's the author's angle?

I think, like most of these business books, the author genuinely wants you to succeed, but he also wants to sell a lot of books.

Who should read this book?

I would say any business owner would probably get some useful pointers on marketing and positioning from this book, but it seems particularly well-suited for someone just starting out.

Specific thoughts: What if I hate marketing, selling, and self-promotion?

The book goes a lot into self-promotion. Though it does a pretty good job of emphasizing that it must be genuine, it’s nevertheless still self-promotion; if you hate that, well… You probably should be working for someone else.

If you are comfortable with a certain amount of genuine self-promotion and you’re trying to attract clients (this book seems particularly aimed at consultants), then this is a great book. Though I’m not sure how much of it is original and how much of it is just Port being a skillful compiler. I know that some of the ideas in here go all the way back to Dale Carnegie, but I assume that Port came up with some of the ideas on his own. In any case I’ve been involved in networking groups of one form or another since 2014, and at this point it feels like a lot of Port’s advice is “in the water”. Which is not to say that it’s unnecessary, more that if you are thinking of doing networking or any other form of marketing it might be a good idea to read this book and give yourself a head start.

Fiction Reviews

The Goblin Emperor

Published: 2014

446 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

After a tragic airship accident kills off his father and three older half-brothers, Maia is returned from exile and thrust onto the throne of the Elven Empire. When you’ve been in exile your entire life being crowned Emperor carries various challenges, and if that were not enough Maia is half-goblin…

Who should read this book?

I saw this book recommended a lot, including by such luminaries as Ross Douthat and Megan McArdle, which is to say lots of people love this book and think you should read it, and who am I to argue. Okay I will argue, but in the next section.

Specific thoughts: I can’t help overthinking things

This is one of those books that goes down quick and easy. It was a delight to consume. And in the immediate afterglow of that experience I even recommended it to a few people, but the more I’ve sat with it (and thought about how to review it) the more uneven it appears. There are items that are ingenious, ways that it’s weird, and bits that are bad. Without attempting to excoriate it or excuse it here’s a half dozen disconnected thoughts:

I think the choice of genre is brilliant. In the past I’ve often said that setting your story at a school is writing on easy mode. I think “outsider thrust into position of power” might be similar. The only other example of this happening in a fantasy setting I can think of is the Empire Trilogy by Raymond E. Feist and Janny Wurts. Outside of that you can see examples of it on TV with Designated Survivor and also in the Jack Ryan series by Tom Clancy. I’m not saying it’s foolproof, but I think it immediately gives the story a very strong start.

Addison does amazing work at creating new words. Rather than using dukes, barons, or counts, she comes up with an entirely new set of terms. And this extends to all sorts of things. The downside to this, is that it makes the book somewhat challenging to listen to. Because not only are you hearing words you’ve never heard before, and which barely make an impression, but she also does that thing where she will refer to people by several different names. I had to grab an electronic copy and refer to it frequently to keep track of everything. Only after I was done reading it did I find out there was a glossary at the back of the book (not included on audio). If you decide to listen to the book, I would definitely start by getting a hold of that and reading it first if possible.

She does similar very interesting work with pronouns and grammar. I’m not sure what exactly the rules are for using the royal we, so I don’t know if she’s just artfully resurrecting an old form of grammar or if she invented her own variant, but it’s done quite skillfully.

I went into this thinking it was the first book of a series. It’s not. It’s a standalone (though there are a couple of other books set in the same universe). And by the end the wisdom of that decision was apparent. The time period and tech level of the novel is basically Victorian, which was also the same time that Dickens was writing. And in the course of things Maia notices many Dickenson elements: poor working conditions, a miserable lower class, gender inequality, etc. In the real world it took the better part of a century to work through all of that, but it’s clear that Addison (and her readers) would not have been able to wait nearly that long if Addison had continued the series. If Addison had tried to continue things it would have gotten either messy or unrealistic or implausible.

Nevertheless, at many points it feels like she’s going to do something with the aforementioned problems, and that she is setting up for a sequel. As one minor non-spoilery example, early on it’s mentioned that the price of coal just keeps rising and rising. You expect that later Maia will find out that while the nobles are partying the economic situation of the rest of the kingdom is spiraling out of control, but nothing of that nature is ever mentioned again. As a result it feels like the book leaves the reader with a lot of loose ends. But since I expected a sequel perhaps it was worse for me than those without that expectation.

But the biggest thing, the thing which grew to overshadow everything else: the antagonists are really incompetent. And when you’re reading the book, that’s a relief, because you don’t want bad things to happen to the main character because you like Maia so much, but once you start reflecting on it their incompetence is extreme enough to be unbelievable. So extreme that as I reflected on it, my entire assessment of the book took a very big hit.

But as I said, and as you can see from reading other reviews lots, and lots of people really love this book. So take everything I say with a large grain of salt.

Red Hook: (The Weird of Hali #6)

Published: 2023

232 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The continuing story of Greer’s “What if Cthulhu and the Old Ones were the good guys?” series.

Who should read this book?

I’ve enjoyed this series (see other reviews here). It's not as flashy as some sci-fi and fantasy series I’ve read, but I think that’s part of its charm—It adds an air of realism to the entire endeavor. Though obviously you shouldn’t read book six without reading the previous five books.

Specific thoughts: New York as she soon will be?

Greer’s day job is as an essayist. He’s a little hard to classify, but you might call him a trad environmentalist. One of the ideas of his I like the most is the theory of catabolic collapse. Lots of people think an apocalypse (or a singularity) is coming. Greer also thinks catastrophe is on the horizon, but his version is far less flashy than most. He believes that collapse will be slow, primarily because we can cannibalize existing resources to keep things going for longer.

In the book Greer gives us a vision of New York in the near future, but rather than being a cyberpunk dystopia like Blade Runner, or haunted zombie-filled ruins, it’s much closer to how New York is now, just much, much… shabbier. And while it’s obviously impossible to say exactly how things are going to go. I find this version more believable.

Within this setting, the main characters are trying to find and help the protagonist from the previous novels while avoiding the evil eye of the Radiance, and soliciting the help of the various Lovecraftian factions. Just like we all are.

He Who Fights with Monsters: A LitRPG Adventure

By: Shirtaloon

Published: 2021

680 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The main character, Jason Asano, is accidentally summoned from our world to a world of magic. As part of the summoning he is granted magical powers to help him understand the new world, in a language familiar to him. This happens to be the language of video games.

Who should read this book?

This is another long, pulpy series that people apparently love (the books average 4.53 on Goodreads and 4.73 on Amazon). It is a fun read, but once again there are ten books! I almost certainly will read all ten, but with a significant dash of grumpiness.

Specific thoughts: It’s lots of fun, but not much happens

The book is twenty-nine hours in audio, as is appropriate for a first book, there’s a lot of world-building. I like world building and my imagination is fired by speculation on where that world building might end up ten books from now. Nevertheless, not a ton happens. Also the protagonist is kind of sanctimonious for my taste. In spite of these complaints I’m looking forward to reading the next book in the series, so I suppose I’m hooked. I may have a problem...

Religious Reviews

All My Knotted-Up Life: A Memoir

By: Beth Moore

Published: 2023

304 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The life story of Beth Moore, from her childhood in Arkansas to her rise to prominence within the larger evangelical community.

What's the author's angle?

Like most memoirs this acts as a defense of all the acts they’ve taken and all the decisions they’ve made. This book is less narcissistic than most, but it’s not entirely free from defensiveness and apologia either.

Who should read this book?

Maybe not me? My wife picked this up for her book club, but it was long enough ago that I had forgotten. I was just mechanically going through my audiobook backlog and knocking things off the list, not realizing that it wasn’t actually on “the list.” Still, it was an interesting peek at a world I wasn’t especially familiar with and an excellent story of faith and overcoming adversity through that faith.

Specific thoughts: The foreignness of evangelicals

Wikipedia describes Beth Moore as “arguably the most prominent white evangelical woman in America.” I’d never heard of her. I suppose this represents a large gap in my knowledge about the world, though one I assume a lot of people share. This is part of why I finished the book, though in the course of reading it numerous other gaps were revealed. Moore covers events in a manner which suggests that I should be deeply familiar with them, and she’s just giving me a small taste of what it was like from the inside. Unfortunately, I was neither deeply familiar, nor even a little bit familiar with the firestorm that erupted when she criticized Trump on social media after the Access Hollywood tape was released. And had almost entirely forgotten about the sexual abuse scandal which rocked the Southern Baptist church starting in 2019.

On a more spiritual level I found the stories about her faith and the way she exercised and demonstrated that faith to be quite profound. On a less spiritual level, I can’t get enough stories about old school southern grandmas and this book had quite a few of those.

Take my dad’s grandmother, Miss Ruthie, for example. She was a hard woman to watch, chewing all that tobacco. At times the foaming saliva was as thick and brown as molasses and, instead of committing to the task with a resolute and plosive puh, she seemed perfectly happy to let it hang. A quarter teaspoon would suspend from her lower lip like it had no place to go. She held onto her spit can like an old country preacher hanging on to his King James.

Reaching the end, this seemed like an unusually light selection. I promise I’ll have something more meaty next time. And that before then I’ll publish something other than book reviews!

I encountered Lockhart's _Lament_ back when I was in college, and I had lots of resentment about it. I can't remember if I actually read it or someone else's article lauding Lockhart, but either way, the sense I got was that the author wanted to do away with problem sets in favor of appreciating concepts and teasing out moments of insight.

The problem is, insight doesn't happen on command. If you the student aren't getting that insight, then staring at your homework page quite possibly won't give it to you either. You can reread the textbook, or go to office hours, or something - there are things that might help - but they might not help immediately. You might end up not having it in time for the homework deadline, or even the exam.

Some people will get that insight quickly, and I'm fine with recognizing them. But I'm not fine with failing everyone else, or even giving them a lower GPA in this age of grade inflation, or making the dedicated students among them keep pounding their heads against the wall.

Yes, if there was a reliable way to teach concept-appreciation and moments of insight, that could be great. But I haven't seen that reliable way, and I don't think Lockhart has either.