Short Book Reviews: Volume II

Authors you might be familiar with: McGilchrist, Hoel, Descartes, Plutarch — Subjects you might be interested in: Opioids, Oppenheimer, Fitness, Rituals — Plus Neuromancer and Expeditionary Force

The Matter With Things: Our Brains, Our Delusions, and the Unmaking of the World (Volume 2) by: Iain McGilchrist

The World Behind the World: Consciousness, Free Will, and the Limits of Science by:

Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company that Addicted America by: Beth Macy

American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer by: Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin

Younger Next Year, 2nd Edition: Live Strong, Fit, Sexy, and Smart - Until You're 80 and Beyond by: Chris Crowley and Henry S. Lodge M.D.

Daily Rituals: How Artists Work by: Mason Currey

Meditations on First Philosophy by: Rene Descartes

Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans by: Plutarch

Neuromancer (Sprawl #1) by: William Gibson

Aftermath (Expeditionary Force #16) by: Craig Alanson

As I mentioned last time I felt the need to take a little bit of a breather. As you can tell by my lack of any essays since then, that breather continues. Still books were read and writing something down about each of them increases the chances that I’ll remember them in the years to come. (Or for that matter in the months to come.) So I’ve done that. Hopefully these reviews will be of some use to you as well.

I- Fiction Reviews

The Matter With Things: Our Brains, Our Delusions, and the Unmaking of the World (Volume 2)

By: Iain McGilchrist

Published: 2021

768 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Volume Two is entirely devoted to discussing the Unforeseen Nature of Reality, which as you can imagine is pretty heavy stuff. It’s mostly an examination of consciousness with a heavy non-materialist point of view.

What's the author's angle?

McGilchrist is the leading popularizer of a nuanced and accurate view of hemispheric differences in how the brain operates. It is his framework for understanding the world, so it’s possible he tries to jam too much into this framework.

Who should read this book?

Recommending a 1600 page two volume work that costs $165 in hardback (and $40 in kindle) is a far more consequential thing than recommending a 300 page book. If you’re interested in this subject, I would read The Master and His Emissary first. If you love that book, then I think it’s worth reading these books.

Specific Thoughts: A Scientific Basis for Rejecting Materialism?

The entire work, all 1600 pages of it, is difficult to compress, and that would be true even if I felt like I had a really good handle on it, which I don’t. The second volume is particularly dense, and not only covers a lot of science but a fair amount of religion as well. In the course of things McGilchrist comes out in support of process theology, which leads to him giving his own take on Pascal’s Wager:

So what is McGilchrist’s Wager? For me, Pascal’s doesn’t quite cover the bases. That’s because I don’t think this is necessarily a matter of ‘either/or’. If you accept that God is in process, as is the cosmos, there is an important third option, much more significant than either of the other two. With Pascal’s Wager, there just is a state of affairs, which we either recognise or do not; we cannot play any part in its coming about. But if it is true that the cosmos depends on us to become what it is, there are three possibilities, not two. Either – as with Pascal – there just is a God, and all depends on our recognising him; or – as with Pascal – there just isn’t a God, in which case nothing is lost by believing; or (per McGilchrist) if God is an eternal Becoming, fulfilled as God through the response of his creation, and we, for our part, constantly more fulfilled through our response to God; then we are literally partners in the creation of the universe, perhaps even in the becoming of God (who is himself Becoming as much as Being): in which case it is imperative that we try to reach and know and love that God. Not just for our own sakes, but because we bear some responsibility, however small, for the part we play in creation (and indeed how ‘big’ or ‘small’ we cannot know: the terms are derived from our limited experience of a finite world).

This idea pairs well with his other claim that consciousness precedes matter. And here I am obligated to give another long quote because I’m not sure I can summarize it adequately:

How on earth might consciousness – immaterial and lacking extension in space as it is – emerge from matter, which is very clearly both material and extended in space? Since, as Colin McGinn reflects, this ‘looks more like magic than a predictable unfolding of natural law’, he suggests ‘the following heady speculation: that the origin of consciousness somehow draws upon those properties of the universe that antedate and explain the occurrence of the big bang … If so, consciousness turns out to be older than matter in space, at least as to its raw materials.’ That would be one very important difference.

In that form it is indeed a speculation, but so is the idea that matter precedes consciousness; by contrast, that consciousness precedes matter is an idea that has an ancient lineage, and more than a little, I shall suggest, going for it. Matter could be born of consciousness without either being the same as, or wholly distinct from, the other. And if true, a form of asymmetry familiar to the readers of this book would operate: mind and matter being aspects of the same thing, but that not of itself making them equal.

…

A long roll call of the most distinguished physicists would support the view that the originary ‘stuff’ of the universe is consciousness. Thus Max Planck was famously asked whether he thought consciousness could be explained in terms of matter and its laws. ‘No’, he replied. ‘I regard consciousness as fundamental. I regard matter as derivative from consciousness. We cannot get behind consciousness. Everything that we talk about, everything that we regard as existing, postulates consciousness.’

Pretty deep stuff which I’m still trying to wrap my head around. In an ideal world I would write a long post distilling things down, but I don’t think I have enough of a handle on it yet. I am going to a conference in San Francisco at the end of March where McGilchrist will be speaking so perhaps after that?

Bottom line, there was a lot going on in this book, but all of it was incredibly thought-provoking.

The World Behind the World: Consciousness, Free Will, and the Limits of Science

By: Erik Hoel

Published: 2023

256 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

It puts forth the strong case that without a theory of consciousness neurology is never going to make any real strides, with an examination of the current state of some possible theories.

What's the author's angle?

Hoel has a PhD in neuroscience and has worked directly on a couple of the theories presented by the book. I don’t know if it’s fair to say that he has a horse in this race, but he has very strong opinions on what that horse should look like.

Who should read this book?

If you’re interested in the latest thinking on consciousness (pun intended) then this is a great overview of things. This is not my normal beat, and as they say, it’s a hard problem, so I found it a little bit dense. Also it was weird to read this book at the same time as I was reading McGilchrist, you will probably not have the same experience.

Specific Thoughts: Good, Bad, and Weird

First let me say that I’m a big fan of Hoel. I’m a paid subscriber to his substack and one of my last major posts took one of his posts and ran with it. I would recommend that you become at least a free subscriber (if subscribing to substacks is something that you do.) But while I unreservedly recommend his substack, I can’t do the same for his book. But that may be more my problem than his. For one thing, as I mentioned, reading 1500 pages of McGilchrist and then following it with 250 pages of Hoel left me with some deep questions I am in no way qualified to answer, and I’m not even sure I have the right set of tools for considering them. Which is to say I would love to see a review of The Matter With Things from Hoel. With the weirdness of my own experience out of the way and my lack of bona fides established, I’m going to attempt to break things down into bite size chunks. Specifically I’m going to list some good points and some bad points.

Good points:

1- Hoel is exceptionally well positioned to discuss the difficulties faced by neuroscience. We hear lots of interesting stuff but according to Hoel, it’s mostly inconsequential, and oftentimes of dubious application. Specifically brain imaging techniques have far less experimental power than we’ve been lead to believe, and as such:

…our study of brains faces increasingly insurmountable problems. I first became aware of these problems as a graduate student in neuroscience, where I was shocked to find that the field is, in secret, outside the eyes of the public and the other sciences, floundering in its attempts to understand the intrinsic, failing in its attempts to explain what we demand it to about minds and consciousness. Its status is, secretly, a scandal.

2- I appreciated his defense of free will. Frequently that’s the first thing that comes up when you’re reading about neuroscience: “Brain imaging scans show that we don’t have free will!” But…

The neuroscientist Benjamin Libet conducted a famous experiment that took advantage of this, one where he had patients watch a clock and remember when they made the decision to make a spontaneous movement. It turned out that the readiness potential started to build prior to when they consciously noted they had made a decision. A huge amount has been made of this experiment. Does it disprove free will? Does consciousness still have a “veto” where it can decide to act contrary to the readiness potential? And so on.

As with many of the big claims in neuroscience that show up in textbooks, recent research has called Libet’s into doubt. Not that he engaged in malpractice or misrepresentation, but rather, using more modern techniques, it was shown to be much harder to tell when a movement would occur prior to the conscious decision to act, at least based on the readiness potential alone.

3- I also really enjoyed his discussion of the rise of the novel as a form of literature and the role it played in expanding on the idea of consciousness and framing what consciousness is. There is an interiority to written novels that is difficult to replicate anywhere else. Of particular interest the novel is much better at that sort of thing than movies, to say nothing of short videos.

4- I also very much enjoyed his discussion of division and scale, both as a general framing problem and as it specifically relates to the brain. At what scale should the brain be studied? At the level of chemicals? At the level of neurons? Should be we looking at regions of the brain? And if we’re dividing things up, where do we draw our lines?

5- The deepest part of the book touches on various discussions of incompleteness, like Gödel’s theorem and Russell’s paradox, all as a way of asking is it possible to have a complete theory of consciousness? But also can consciousness understand consciousness?

Bad Points:

For me the bad points of the book all relate to the medium. Writing books is a different discipline than writing a newsletter, or making a podcast for that matter. And frequently the skills that make someone a master of one medium may not translate quite as well to other mediums. You may be familiar with Dan Carlin and his podcast Hardcore History. He wrote a book, The End Is Always Near (my review) and it was not as good as one of his podcast episodes. For one thing they had edited out all of his interesting asides, and the tone was far less conversational.

I feel like something similar is going on with Hoel and this book, the writing in the book comes across as more stilted than in his posts. I suspect that one of his editors urged him to be more formal, and it was a mistake. Also, most of the chapters weren’t as good as his best posts. But of all the problems the worst was that he didn’t really establish a through line for the book. It felt disconnected and almost more like a collection of essays than a book with a persistent thesis.

Bottom line for me is you should definitely subscribe to Hoel’s substack, and you can probably skip Hoel’s book. But after reading the substack for awhile you’ll also be able to form your own opinion on things.

Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company that Addicted America

By: Beth Macy

Published: 2018

560 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The rise of the opioid crisis with a particular focus on Appalachia, one of the hardest hit and earliest areas to be rocked by the crisis.

What's the author's angle?

The story of opioids and Appalachia was a story that needed to be told, and, as a semi-local journalist, Macy was in a position to do just that.

Who should read this book?

I’ve read at least four books chronicling the opioid crisis: Empire of Pain by Patrick Radden Keefe, The Hard Sell by Evan Hughes, and Dreamland and the Least of Us by Sam Quinones (the preceding links go to my respective reviews). If you’re only going to read one book on the crisis I would read Dreamland. If you want to have a specific person (or family) to blame read Empire of Pain. None of this is to say Dopesick isn’t a great book, merely that those other two are fantastic, and Dopesick doesn’t add very much.

Specific Thoughts: Beyond Good and Evil Lies Opioid Acceptance

To the extent that this book differs from the other books I’ve mentioned it’s that it leans harder into solution advocacy. In particular a paradigm of harm reduction and advocacy for medication assisted treatment (MAT). That latter is in opposition to the more traditional Alcoholics Anonymous (or, in this case, Narcotics Anonymous) methodology which eschews all reliance on substances.

Both of these are interventions which occur after someone is already addicted. Obviously it’s better if they never get addicted in the first place, and this appeared to be the main justification for the War on Drugs.. But most people on the front lines of the crisis have decided that war has been an abject failure, and now they’re looking for something else to try. This certainly includes not flooding the country with legal opioids, but that horse has already been let out of the barn. Which leaves us with harm reduction—a major focus of the book.

Certainly I am very, very interested in finding something that reliably puts addiction into remission, and it does seem that MAT strategies have a higher success rate than “cold turkey” strategies. On the other hand, harm reduction policies have been more of a mixed bag. Two cities that have been at the forefront of this strategy are Vancouver and San Francisco. A recent study about Vancouver’s program concluded that:

Two years after its launch, the Safer Opioid Supply policy was associated with greater prescribing of safer supply opioids but also with a significant increase in opioid-related poisoning hospitalizations.

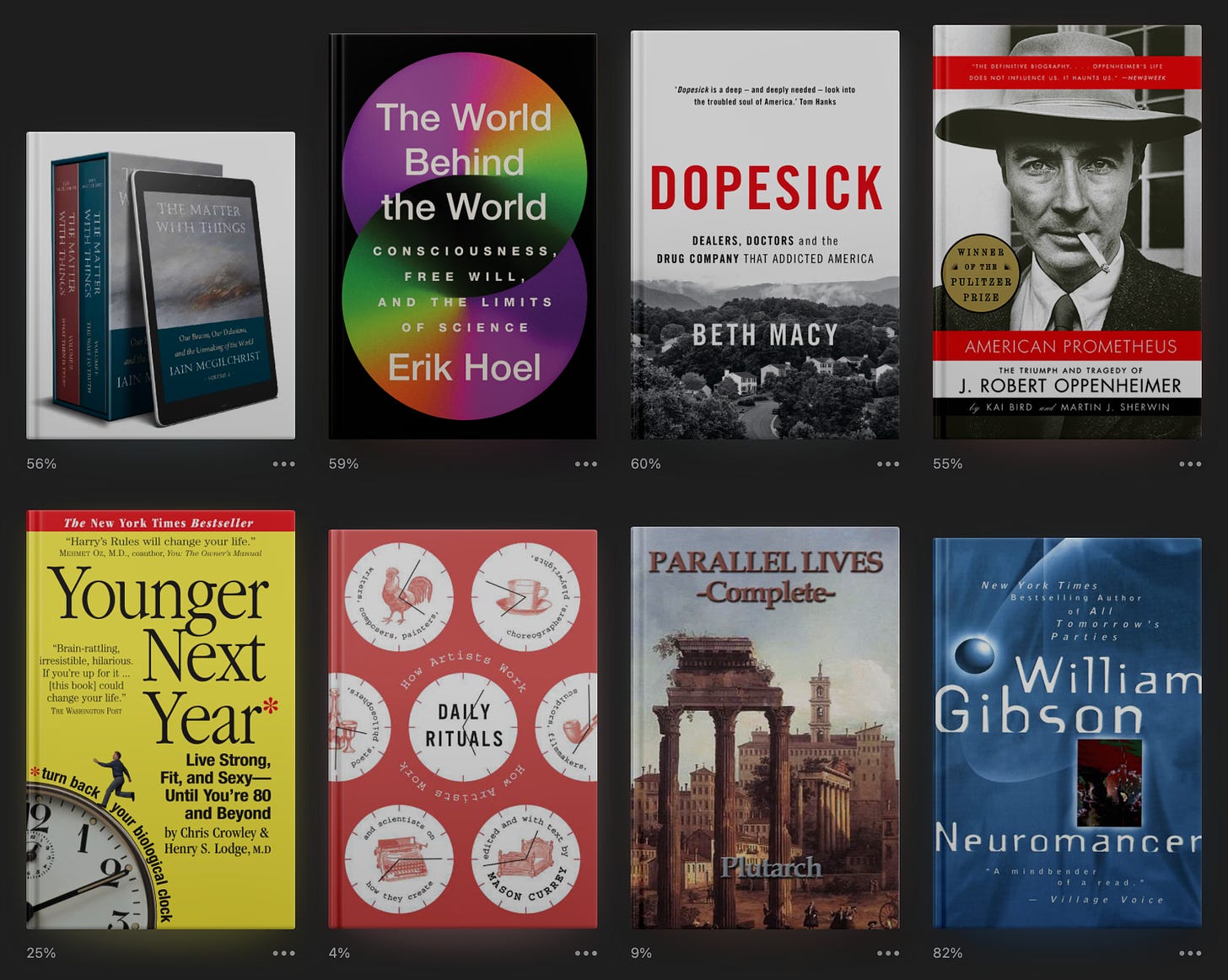

For results in San Francisco, which has a similar policy to Vancouver, we turn to this graph from the New York Times:

A huge spike in overdose deaths started right around the time these harm reduction policies were implemented.

For many people, including Macy, Portugal is the gold standard for this approach. I came across an article which pointed out that in 2017 72,000 people died from overdosing in the US, and that if our overdose rate had been the same as Portugals that fewer than 800 people would have died. That’s an interesting observation, but I very much doubt that it’s entirely due to the difference between our “War on Drugs” strategy and their harm reduction strategy. Also, while it has taken longer, Portugal seems to be having some of the same problems San Francisco is:

Portugal became a model for progressive jurisdictions around the world embracing drug decriminalization, such as the state of Oregon, but now there is talk of fatigue. Police are less motivated to register people who misuse drugs and there are year-long waits for state-funded rehabilitation treatment even as the number of people seeking help has fallen dramatically. The return in force of visible urban drug use, meanwhile, is leading the mayor and others here to ask an explosive question: Is it time to reconsider this country’s globally hailed drug model?

I understand the impulse to treat drugs as a disease to be managed rather than war to be won. Having read the book, I have all the sympathy in the world for treating addicts more charitably. But is it really the best solution to surrender to the idea that a high percentage of society are just going to be lotus eaters?

American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer

By: Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin

Published: 2019

572 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

This is the book on which Christopher Nolan based his recent movie.

What's the author's angle?

The author was clearly very sympathetic to Oppenheimer. The book isn’t a hagiography, but I’d be surprised if there wasn’t some degree of bias.

Who should read this book?

Most people are going to be wondering “If I liked the movie, should I read the book?” I’m going to say that for most people the answer is no; the movie is entirely adequate and covers most of the interesting bits.

Specific Thoughts: So What Got Left Out of the Movie?

If the movie only covers most of the interesting bits your immediate question is: What are the interesting bits it doesn’t cover? I can't answer that question exhaustively (if nothing else I don’t know what you find interesting) but I did note three items which jumped out at me.

Oppenheimer was one of only two students to sign up when Alfred North Whitehead came to Harvard to teach class covering Principia Mathematica.

I’ve heard that physicists get mad when you try to apply quantum mechanics outside of physics. Like saying it might explain consciousness, or even more woo things like love. Apparently Bohr did that sort of thing all the time and was constantly trying to apply complementarity to everything.

While Lewis Strauss was just as petty and vindictive as displayed in the movie (possibly more so) much of the conflict was actually driven by interservice rivalry between the Strategic Air Command and the Army. The former was very interested in thermonuclear weapons, while the Army was more interested in conventional forces backed up by tactical atomic weapons. It’s interesting how often you encounter bureaucratic infighting when you dive into controversies like the one that engulfed Oppenheimer.

My suggestion? Watch the Oppenheimer movie, but then if you’re going to read a topical book about it, I recommend The Making of the Atomic Bomb by Richard Rhodes.

Younger Next Year, 2nd Edition: Live Strong, Fit, Sexy, and Smart - Until You're 80 and Beyond

By: Chris Crowley and Henry S. Lodge M.D.

Published: 2019

400 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Health and wellness mostly through exercise for older individuals

What's the author's angle?

This book has a great dynamic, you have Crowley who is just an old guy looking for better health and then you have Lodge who is the doctor who told him what he needed to do. Crowley was so impressed that he talked him into partnering on a book (they alternate chapters).

Who should read this book?

Everyone over 50 probably. This book comes with a similar calculation to books claiming to increase productivity. If it works even a little bit it’s obviously worth reading. Spending eleven and a half hours (on audio at 1x) to live just one year longer is obviously a great trade.

Specific Thoughts: I’m an Old Guy and I Think I Need This Book

I’m reading this as part of a book club with some other old guys and everyone loves it. My favorite thing about the book is that it feels accessible. The tone is very engaging. The advice is straightforward, and Crowley’s energy and enthusiasm is very infectious.

Daily Rituals: How Artists Work

By: Mason Currey

Published: 2013

278 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Numerous short descriptions of the rituals and habits of famous creatives.

What's the author's angle?

Tim Ferris was instrumental in getting this book out there. (The audiobook was produced by Tim Ferris Audio.) Both Ferris and Currey have a strong belief in learning from the masters. Having read this and similar books (in particular I’m thinking of Ferris’ Tools of Titans) I’m less convinced, you can get too much advice. Particularly this book where only a tiny amount of time was spent on each person.

Who should read this book?

I think the stories are interesting, so if you like historical vignettes it’s a great book. I’m not sure of its efficacy as a personal productivity book.

Specific Thoughts: Successful People Are All a Little Bit Weird

If you’re looking for one hard and fast rule for being creative that applies universally you’re not going to find it here. (Walking came close,) The individuals profiled had as many different strategies for being productive as there were profiles (or just about). A majority stuck to a routine, but even here there was quite a bit of variation. My takeaway: find something that works for you and cling to it like grim death.

Meditations on First Philosophy

By: Rene Descartes

Published: 1641

120 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Most references to this book (including the one above) leave out the subtitle of the book. The full title is:

Meditations on First Philosophy in which the existence of God and the immortality of the soul are demonstrated

And that’s a pretty good summation.

What's the author's angle?

I agree with Descartes that God exists, but his proof of God stuck me as question begging (in the original sense) that he assumed what he had set out to prove.

Who should read this book?

This is one of those shorter classics that while still dense is also entirely tractable with a little bit of effort. So if you’ve ever even considered reading it I would go ahead and do so.

Specific Thoughts: How Descartes Ruined the World

This was another selection of the local SSC/ACX book club. Unfortunately I came down with COVID a few days beforehand so I couldn’t attend. As a result I can really only report back on what I thought of it, which is too bad, because I had hoped to engage in a discussion of the unintentional, but very pernicious side effects of Descartes’ philosophy.

I’m speaking of the modern belief in an internal locus of truth. That inside everyone is an “authentic self” and if you dig deep enough you will find this “self” and it will give you all the truth necessary for a happy existence. As an example I offer up a quote I came across recently:

True belonging is the spiritual practice of believing in and belonging to yourself so deeply that you can share your most authentic self with the world and find sacredness in both being a part of something and standing alone in the wilderness. True belonging doesn’t require you to change who you are; it requires you to be who you are.

If I’m going to be frank, this is utter garbage. It’s outside of the scope of a book review to demonstrate this, but if you’re curious read The World Beyond Your Head by Matthew Crawford (see my review here).

The whole point of this discursion is that one could make a credible case that this sort of solipsistic epistemology started with Descartes, and that therefore he bears some responsibility for our present crisis.

Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans

By: Plutarch

Published: Sometime around 110 AD

1333 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

This is one of the great books of the Western World. Plutarch has composed biographies of forty-eight notable Greek and Roman leaders. He presents them two at a time and then compares and contrasts them. Much of what we know about these individuals comes from this book.

What's the author's angle?

It seems obvious that Plutarch was hoping to encourage certain virtues in his readers. As such the stories can be a little bit heavy-handed, and the virtues he encourages are not always what we would consider virtuous.

Who should read this book?

I think everyone should read selections from Plutarch. Reading the entire thing is another matter, but if you think you have the time it’s a very interesting experience.

Specific Thoughts: The Anecdotes of Plutarch

Given this book’s length I should have all sorts of things to say. And I do, what I don’t have, à la Pascal, is the time to make it short enough to fit into a review. The lives are pretty readable. There are a lot of names, but you can mostly follow the major players and of course subjects of one life will show up in another life. It’s also interesting and illuminating to read the original source for a story, rather than see it related by someone else centuries later.

But the aspect of this book I liked best were the short anecdotes, almost always followed by a trenchant quip at the end. It appears there’s actually a name for these things they’re called apophthegm, though I also came a across a greek word for them, χρεία, which translates as need? I have zero knowledge of greek and I’m already in over my head, so I’ll just present a few of these apophthegmata:

Of his son, who lorded it over his mother, and through her over himself, [Themistocles] said, jestingly, that the boy was the most powerful of all the Hellenes; for the Hellenes were commanded by the Athenians, the Athenians by himself, himself by the boy's mother, and the mother by her boy.

At the very moment that the fleet was ready to sail and when Pericles embarked upon his trireme, an unexpected eclipse of the sun occurred. Suddenly it grew dark and everyone was terrified by this sight, reading into it some terrible omen. Pericles, however, when he noticed that the steersman of the ship was also overcome by great fear and total helplessness, covered his face with his cloak and asked, “And do you think that this is also something terrible or a bad omen?” When the steersman answered no, Pericles asked again, “In what way does the first phenomenon differ from what I did? Surely in no way whatsoever, except that the object causing the eclipse of the sun must be bigger than my coat.”

When Hannibal seized Tarentum, the leader of the defending Roman contingent was Marcus Livius. Although he had lost the town, he barricaded himself in the town’s citadel and kept it in his control until the town was won back by the Romans under the leadership of Fabius. Livius was later very envious of Fabius’ fame and once, driven by envy and ambition, he spoke in the senate, saying, “I, not Fabius, am responsible for the retaking of Tarentum”. At this, Fabius laughed and said, “You’re completely right, Livius. For had you not lost the town, I would have had nothing to retake!”

I remember getting these same sorts of stories when I was younger. For example, George Washington chopping down the cherry tree and responding when asked that he could not tell a lie. Now of course that story was made up by one of Washington’s biographers. And it’s fair to say that some of the stories in Plutarch were similarly made up, and any that weren’t are probably embellished. And yet in expunging them from our discourse doesn’t it feel like the world is just a little bit less interesting?

II- Fiction Reviews

Neuromancer (Sprawl #1)

By: William Gibson

Published: 1984

278 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

One of the founding documents of the cyberpunk genre, it follows Case, a down-on-his-luck hacker, and Molly, a razorgirl, as they pull off a high stakes infiltration job in the near future.

Who should read this book?

If you’re into modern science fiction, AI, or dystopia, this book is basically required reading.

Specific Thoughts: Gibson Is a Stylist, Not a Plotter

Gibson is a great stylist, and this book is very stylish. Of course that can result in a certain amount of opaqueness. Which is why I read this book for the third time, because I wasn’t sure I was getting it, so I decided to read it, in physical form, pen in hand, away from my computer or any other distractions. The first time I read it was in 1989. I listened to it in 2016, I don’t recall at what speed, but it almost certainly wasn’t 1x. And while I enjoyed it both times, I always felt like I was missing something that a more careful reader would have picked up. So I finally read it as carefully as possible, and?

I certainly picked up more than I had on my previous read-throughs, but also it became apparent that in large part it was Gibson not me. There are definitely spots where he doesn’t explain things and it doesn’t matter how carefully you read, you’re just not going to get it. (I’m thinking in particular of Riviera with all his “powers”.) And also plot elements that just don’t make sense. (Why does Hideo leave 3Jane? Isn’t he a bodyguard?) Despite all this, the prose is quite lovely. Here are some quotes I noted on this read through:

THE SKY ABOVE the port was the color of television, tuned to a dead channel.

Night City was like a deranged experiment in social Darwinism, designed by a bored researcher who kept one thumb permanently on the fast-forward button.

There were countless theories explaining why Chiba City tolerated the Ninsei enclave, but Case tended toward the idea that the Yakuza might be preserving the place as a kind of historical park, a reminder of humble origins. But he also saw a certain sense in the notion that burgeoning technologies require outlaw zones, that Night City wasn’t there for its inhabitants, but as a deliberately unsupervised playground for technology itself.

The lenses were empty quicksilver, regarding him with an insect calm.

Every AI ever built has an electromagnetic shotgun wired to its forehead.

“You are worse than a fool,” Michèle said, getting to her feet, the pistol in her hand. “You have no care for your species. For thousands of years men dreamed of pacts with demons. Only now are such things possible. And what would you be paid with? What would your price be, for aiding this thing to free itself and grow?”

That’s king hell ice, Case, black as the grave and slick as glass. Fry your brain soon as look at you.

“How do you cry, Molly? I see your eyes are walled away. I’m curious.” His eyes were red-rimmed, his forehead gleaming with sweat. He was very pale. Sick, Case decided. Or drugs.

“I don’t cry, much.”

“But how would you cry, if someone made you cry?”

“I spit,” she said. “The ducts are routed back into my mouth.”

“Then you’ve already learned an important lesson, for one so young.” He rested the hand with the pistol on his knee and took a bottle from the table beside him, without bothering to choose from the half-dozen different liquors. He drank. Brandy. A trickle of the stuff ran from the corner of his mouth. “That is the way to handle tears.”

I’d been dreaming, you see. For thirty years. You weren’t born, when last I lay me down to sleep. They told us we wouldn’t dream, in that cold. They told us we’d never feel cold, either. Madness, Molly. Lies. Of course I dreamed. The cold let the outside in, that was it. The outside. All the night I built this to hide us from. Just a drop, at first, one grain of night seeping in, drawn by the cold. . . . Others following it, filling my head the way rain fills an empty pool. Calla lilies. I remember. The pools were terracotta, nursemaids all of chrome, how the limbs went winking through the gardens at sunset. . . . I’m old, Molly. Over two hundred years, if you count the cold. The cold.

Aftermath (Expeditionary Force #16)

By: Craig Alanson

Published: 2023

697 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The continuing adventures of Joe and Skippy.

Who should read this book?

If you don’t already know who Joe and Skippy are you definitely shouldn’t read this book. I personally vacillated quite a bit. The original series ended with book 15, so that would have been a good place to stop, but a couple of people who had started the series on my recommendation said I should read book 16. So I guess my assessment is that if you’ve read the first 15 and you’re on the fence then you should read this one too.

Specific Thoughts: Really? Sixteen Books?!?!

The plot was nothing to write home about. The conflict was very similar to the sort of conflict one might see in the first 15 books. The characters were charming, but nothing new was added in this book, not even any new characters. Still, the book went down easy, like that bag of potato chips that is there one moment and in your belly the next. I’m not necessarily saying it’s junk food, more that it’s comfort food.

You may have noticed that I’m trying something new with one of my standard sections. If you have any “specific thoughts” about this or any other topic feel free to reach out. One of the best things about this blog has been the many great conversations I’ve had with strangers, many of whom are now friends. Should you be interested in that you can email me directly at wearenotsaved at gmail.