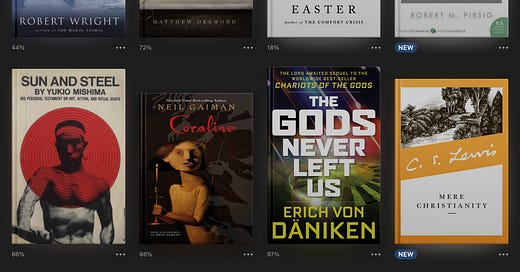

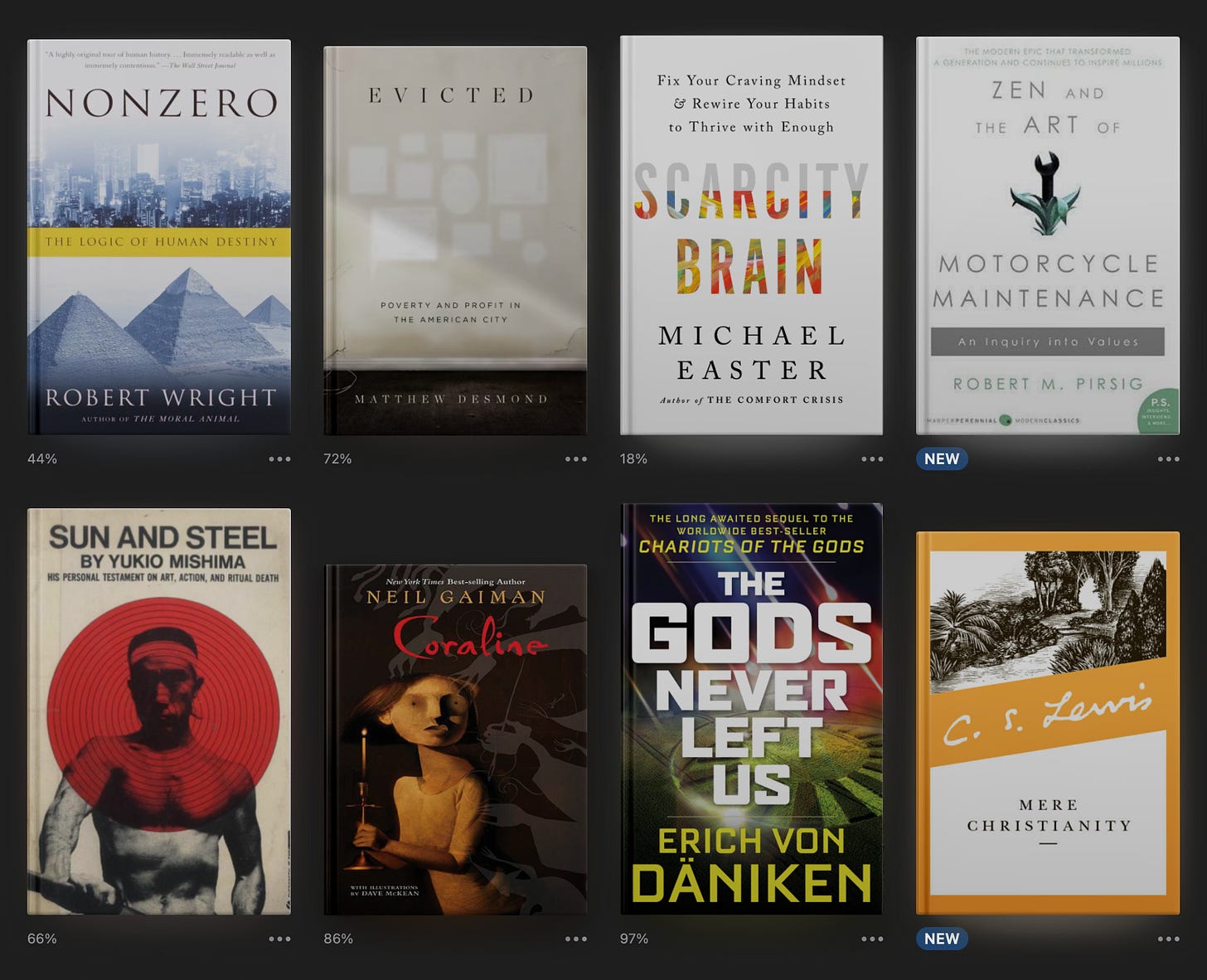

The 10 Books I Finished in November

Robert Wright, Matthew Desmond, Michael Easter, Robert Pirsig, James Carse, Nick Hornby, Yukio Mishima, Neil Gaiman, Erich von Däniken, C. S. Lewis

Nonzero: The Logic of Human Destiny by: Robert Wright

Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City by: Matthew Desmond

Scarcity Brain: Fix Your Craving Mindset and Rewire Your Habits to Thrive with Enough by: Michael Easter

Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry into Values by: Robert Pirsig

Finite and Infinite Games by: James Carse

Fever Pitch by: Nick Hornby

Sun and Steel by: Yukio Mishima

Coraline by: Neil Gaiman

The Gods Never Left Us by: Erich von Däniken

Mere Christianity by: C. S. Lewis

It’s likely that November is my favorite month. First off I will match fall in Utah against fall anywhere else in the world as the best season and the best place for that season. Secondly, it contains Thanksgiving which doesn’t quite beat out Christmas as my favorite holiday, though it’s close. Third, it’s full of pregnant potential for Christmas and the end of the year with the accompanying relaxation and reflection. In November you get to enjoy all the anticipation of what’s coming. And as we all know anticipation is often, or even mostly, better than the real thing. Finally, while I know I am atypical in this respect, it’s finally and definitely cold, and that cold is going to last for several months yet. The hellish inferno of July is but a distant memory…

I think I may also be atypical in how much I look forward to the end of the year as a time to take stock of how things have gone — to double down on what went well and figure out how to fix what went poorly. Looking back I’m not happy with my writing efforts. There are lots of reasons for that, and most of them are entirely reasonable, and understandable, but that doesn’t mean that there’s not room for improvement. I’m definitely going to make some changes come the New Year. I’m not quite ready to announce them, but check back in a month.

For now it’s enough to hope that your Thanksgiving went well, and to wish you beyond that a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year!

I- Eschatological Review

Nonzero: The Logic of Human Destiny

By: Robert Wright

Published: 1999

448 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The arc of evolution is long but it bends towards nonzero-sum games.

What's the author's angle?

Wright is a technology booster and an internet pioneer. He has a lot of eggs in the “technology is a force for good” basket.

Who should read this book?

People looking for an arc to history that (mostly) doesn’t involve a read-between-the-lines mysticism.

General Thoughts

First off, because the concept is so central to the book, it would be good to remind people what nonzero-sum games are. A game is zero sum if one player's gain is another player’s loss. Let’s imagine that four friends each have $100 and they’re trying to decide how to spend an evening together. One option would be to play poker. Poker is a zero sum game. At the end of the night the total amount of money will still be $400, it will not have gone up, but one or two of the friends will have quite a bit more than the $100 they started with while the rest of them will have quite a bit less, and some of them might end the night with no money at all.

Another option would be to create something for sale — lets say wooden toys. (Christmas is coming up…) Imagine that one of them has access to his father’s wood-working shop, another is great at toy design, still another is a talented painter, and the final one has experience marketing things on Etsy. They might pool their $400, use it to buy some supplies, and spend the evening making toys to sell. A few weeks later, when all the toys are sold they would end up with far more than $400. And whoever purchased the toys would have a delightful toy to give to their child. They were still, in effect, playing a game that evening, but it was nonzero-sum: everyone involved ended up better off.

A couple of important things to note. First, if you think that the nonzero-sum game I described is just capitalism, then you’re not wrong. This is, in fact, one of the major benefits of capitalism, it assists in the creation and execution of nonzero-sum games.

Second you’ll note that the friends had to wait for their money, meaning that time preference is a factor. Nonzero-sum games often require people to have a low time preference — in order to engage in them people have to place as nearly as much value on future money as they do on present money.

As you might imagine from this, Wright is a big booster for both capitalism and anything that creates low time preference. In this way the book feels very similar to some of the other books I’ve read. In fact Wright’s book felt like someone had combined Joseph Henrich’s books (The Secret of Our Success, The WEIRDest People in the World) with Steven Pinker’s books (Better Angels of Our Nature, Enlightenment Now). So much so that I would accuse Wright of being derivative, except his book came first, So I guess it’s Pinker and Henrich who are refining the ideas that Wright already proposed?

In Pinker’s case I’m not sure he’s actually offering up any refinements. Pinker argues that the march of progress is unstoppable, and as such we’re richer, smarter, and less violent than our ancestors. But he doesn’t spend much time talking about an underlying mechanism for this process, and to the extent that he does it’s a worrisome one. Pinker gives much of the credit to “The Leviathan”, i.e. increasingly intrusive government, as a major factor. But he never once mentions nonzero-sum games/thinking or Wright’s book. Having read Wright’s book, I’m surprised by that. I would have expected it to be a significant influence.

It used to be if someone was curious about something you would Google it, these days one asks Chat GPT. Here was its response:

Steven Pinker is indeed familiar with Robert Wright's book "Nonzero." In a critique of Wright's progressivism, Pinker acknowledges agreement with Wright on certain points, such as the increasing complexity of biological organisms and cultures over time and the presence of cultural and moral progress. However, Pinker challenges Wright's perspective on the direction and purpose of this progress, particularly questioning the idea of an inherent "goal" or "destiny" in the evolution of complexity and cooperation.

This seems like a strange criticism to make. My read on Pinker is that he wants to advocate for durable progress, but without being pinned down to any kind of mechanism. Well if you don’t understand the mechanism how do you know that it’s durable? Also Wright’s proposed mechanism of nonzero-sum games seems like something well within the bounds of scientific theories and discourse. I would have thought Pinker would welcome it.

Nevertheless, to be fair to Pinker, by the end of the book Wright get’s pretty speculative, and starts talking about Teilhard de Chardin and his idea of the noosphere: A world-wide group mind. In Wright’s estimation this group mind would be one giant nonzero-sum game that encompassed the enter world. Once you remember that the book was published in 1999, you can forgive Wright for his optimism, and obviously he was not alone in these hopes. Lots of people were wrong. Wright got everything right but the direction:

This doesn’t mean that combatting global warming will lead to a transnational lovefest. But it is evidence that, as global interdependence thickens, long-distance amity can in principle grow even in the absence of external enmity. And it’s something to build on. There is no telling what it could mean as technology keeps advancing; as the World Wide Web goes broad bandwidth, so that any two people anywhere can meet and chat virtually, visually (perhaps someday assisted, where necessary, by accurate automated translation). One can well imagine, as the Internet nurtures more and more communities of interest, true friendships more and more crossing the most dangerous fault lines—boundaries of religion, of nationality, of ethnicity, of culture.

The common interests that support these friendships needn’t be high in gravitas. They can range from stopping ozone depletion to preserving Gaelic folklore to stamp collecting to playing online chess. The main thing is that they be far-flung and cross-cutting. Maybe this is the most ambitious realistic hope for the future expansion of amity—a world in which just about everyone holds allegiance to enough different groups, with enough different kinds of people, so that plain old-fashioned bigotry would entail discomfiting cognitive dissonance. It isn’t that everyone will love everyone, but rather that everyone will like enough different kinds of people to make hating any given type problematic. Maybe Teilhard’s mistake was to always use “noosphere” in the singular, never in the plural. Maybe the world of tomorrow will be a collage of noospheres with enough overlap to vastly complicate the geography of hatred. It wouldn’t be Point Omega, but it would be progress.

This is all territory I covered in my last post. The internet has not worked out the way Wright hoped it would. We have ended up with a collage of something, and a different geography. But in the vast majority of cases things have gone in a direction opposite the one Wright imagined. It's a collage of negative egregores, and our virtual geography has ended up with far more hate, rather than far less.

Eschatological Implications

Perhaps this virtual geography of hate is only a temporary setback. Perhaps when our distant ancestors write their hundred thousand year history of humanity our present discord will not even deserve a footnote. Wright himself seems to have reacted by leaning into Buddhism and mindfulness. (Presumably another reason why Pinker doesn’t like him.) He claims Buddhism is:

Not just… true—which is to say, a way out of our delusion—but that it can ultimately save us from ourselves, as individuals and as a species.

Are our fevered delusions temporary? We can file that question as being one aspect of the great question of our time:

Is NOW different? And if so how?

In the book Wright seems to be arguing for both sides of things. To begin with he’s arguing that the trend towards nonzero-sum games has been going on for billions of years. If this trend has been going on for that long then it’s unlikely that our particular moment has anything special going for it, or that we should be particularly concerned for the long term. In spite of this Wright definitely is concerned. His list of concerns are not that much different from the concerns shared by a lot of people: Nuclear war, global warming, bad leaders, etc. He’s so worried in fact that he wants us to slow progress down. To turn down the dial on exactly the mechanism he’s championing.

Though the topic doesn’t come up in the book, I see strong echoes of the debate over Fermi’s paradox. If Wright’s theory of progress is accurate, alien masters of nonzero-sum games should have already taken over the galaxy sweeping us up in those games, and yet the universe is unaccountably silent. Why? If we read between the lines a bit the only reasonable interpretation is that Wright is among those who think that the Great Filter is ahead of us.

The book highlights one possible candidate for the filter that doesn’t get a lot of attention. As Wright tells it these nonzero-sum games develop from the fact that groups are in competition. Whether it’s species competing at the level of natural evolution or nations at the level of cultural evolution. And yet continued national competition in the age of nuclear weapons has the potential to be catastrophic. Wright predicted that we would avoid this when the world came together in one harmonious whole (the 90’s were so optimistic). It’s a nice idea, but given how central the role of competition is in Wright’s narrative, it might also end up being fatal to further progress. Basically, if we’ve implemented a nonzero-sum game at the highest level, what need is there for further development of these games? We’ve removed the competitive incentive.

Over a long enough time horizon I think Wright is correct. The graph has gone up, but that doesn’t mean that there isn’t the occasional gigantic disruption. As one example I was recently reading about historic mass extinctions, for example the Permian–Triassic extinction event of 252 million years ago which killed off 53% of marine families, 84% of marine genera, about 81% of all marine species and an estimated 70% of terrestrial vertebrate species. Clearly there was a point where things were very zero sum.

Finally, even if the graph has gone up, and nonzero-sum games do, on average, continually increase, it nevertheless seems possible that we might reach the edge of the playground. That it’s easy to develop and spread these games within the confines of a single biosphere but eventually you run out of space, and jumping to a new biosphere is prohibitively difficult. This might be where we’re at, and it might be that when you reach the edge of the playing field the game changes in a broad and brutal way.

II- Non-Fiction Reviews

Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City

By: Matthew Desmond

Published: 2016

432 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

An on the ground examination of evictions in Milwaukee from the perspective of both tenants and landlords.

What's the author's angle?

Desmond is an academic with a specific focus on issues related to poverty. He’s actually the principal investigator for the Eviction Lab, so this issue is pretty close to his heart.

Who should read this book?

If you want an accurate representation of extreme poverty in America, it doesn’t get much better than this.

General Thoughts

This book reminded me of Gang Leader for a Day by Sudhir Venkatesh (see my review here). In both books an academic embeds himself deep into a world we normally don’t get to see, and in the process illustrates the hidden organization and incentives which structure people’s behavior. These books end up being particularly enlightening because from the outside the incentives are not apparent, consequently the behavior of the very poor can seem completely irrational. To be sure rationality is not something they excel at, but given the constraints they’re under, most of their decisions are pretty clear-headed.

This book also reminded me of Life at the Bottom by Theodore Dalrymple (see my review here). The people Dalrymple describes are not as rational as those described by Desmond and Venkatesh, but then Dalrymple was dealing with extreme adverse selection. (He worked as a psychiatrist at hospitals and prisons.)

What all three have in common is that the government, rather than being a source of stability, is a force of chaos and disruption. Occasionally they help but even more frequently they throw a wrench into the whole process. Standards designed to protect renters end up making it difficult or even impossible for the impoverished to rent period. Benefits are difficult to acquire, and keep. Additionally, while I saw no evidence that renters risked death by calling the police, they definitely risked eviction. Every time the cops were called it was counted against the landlord, which meant that they were very much incentivized to evict anyone who called the police. This seems like an undercovered aspect of the belligerent relationship most poor people have with the authorities.

Despite the chaos visited on these people by the government, Desmond’s solution is even more government in the form of housing vouchers. And perhaps they would prove to be a silver bullet. But one can’t help getting the impression from this book and the others that, as we approach the 60th anniversary of Lyndon Johnson declaring a war on poverty, victory may be farther away than ever.

Scarcity Brain: Fix Your Craving Mindset and Rewire Your Habits to Thrive with Enough

By: Michael Easter

Published: 2023

304 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The fact that humans were raised to expect conditions of scarcity, and how those evolutionary expectations misfire when humans are put in positions of abundance.

What's the author's angle?

Easter is trying to become the mainstream face of hard living. This book was a follow up to his first book The Comfort Crisis (see my review here).

Who should read this book?

If you really liked The Comfort Crisis you’ll probably like this book. Particularly if you’re not hypercritical (like me).

General Thoughts

This book has a lot of good stories (I’ll include my favorite at the end of the review) and a lot of interesting observations, but these stories and observations didn’t cohere very well. Easter’s strength is going places and doing things (in this book he describes a trip to Iraq, a journey into the backcountry to do antler hunting, and a seven day stay in a Benedictine Monastery) but he largely failed to string these stories of adventure into a coherent theory of how the world works. Personally, I got the sense that the book was rushed out as a way of capitalizing on the buzz from his first book.

He opens with a discussion of addiction. When they study addiction in animals it turns out you get differing rates of addiction depending on whether the animal is kept in a tiny cage vs. given an environment similar to their natural environment. You may have heard of Rat Park, the same sort of thing happens with pigeons. If you keep them in a small enclosure and allow them to trigger the dispensing of a variable amount of an addictive substance they will go crazy with that trigger — oftentimes to the point where they ignore food and water. But if you give the pigeons a space to explore and room to fly, then they do not get addicted.

Easter’s theory is that living things need a certain amount of stimulus, and they get it however they can. So if a pigeon can’t get it by flying around and exploring they’ll get it through the random distribution of a drug. Easter asserts that the same thing goes for humans. If they can’t get natural stimulation they’ll turn to artificial stimulation, and that’s how people end up addicted to gambling or drugs.

He attempts to map this onto a mechanism he names the scarcity loop, which consists of the following steps:

Opportunity to obtain something valuable

Unpredictable payout on that valuable item

Quick repeatability of the process

Together these represent stimulation and Easter’s assertion is that if we get sufficient natural stimulation — largely by being in nature — we won’t be tempted by artificial stimulation. The problem with this is twofold:

First, it’s undermined by his own examples. He starts the book with a discussion of the Iraqi drug trade, and links addiction to past and ongoing violence in Iraq. But most of the people he describes are getting plenty of stimulation. Now it might be the wrong sort, or there might be too much of it, but Easter makes almost no attempt to connect it to his larger thesis (a failing common to most of the stories he tells). On the other side of things he ends the book by discussing Benedictine monks, offering them up as exemplars of health and vitality. But they violate all of the rules Easter already established. Their lives are the opposite of stimulating. They maintain exactly the same daily schedule for decades. There is no unpredictability, no unexpected stimulation, no potentially valuable rewards to be had.

Second, he doesn't ever discuss supernormal stimuli (see my discussion of the phenomenon here). Evolution built in numerous protections against scarcity — which the book touches on, but not nearly enough when you consider the title — but there are essentially no guardrails against abundance. Accordingly when we encounter abundance we can end up behaving in bizarre counterproductive ways. Technology can simulate this abundance in ways that convince us to work against our best interests. For some great examples see my review of Addiction by Design.

Easter doesn’t acknowledge the possibility of this problem and in fact ends up being something of an apologist for both the gambling industry and the tech industry. Basically saying that if we lived in a way that was more in tune with nature we’d be like the pigeons and we wouldn’t have to worry about addiction. Perhaps, but those industries are often a big part of the reason we don’t live more in tune with nature…

Having said all this you’re probably surprised that I gave the book a soft positive recommendation. As I said, a lot depends on how critical you’re going to be. I’m hypercritical and thus the complaints. But it’s probably worth it just for the stories. I mentioned I’d share my favorite.

An engineering professor is building a lego bridge with his three year old son. The son is working on one side and the professor is working on the other. When they finish the bridge isn’t stable. The son’s side is shorter than the professors. So the professor grabs some more blocks. Meanwhile the son removes some blocks from his dad’s side. When the professor sees this he realizes it’s clearly the better solution. It uses fewer resources, and it’s more stable than the version made with more blocks.

The professor wonders why his first thought was to add more, and wonders how widespread this impulse is. So he starts conducting some experiments where people are tasked with improving something and the best answer is to remove some elements. And essentially everyone wants to add elements. Even when the experiment charged them fake money the more elements they used. Even when they were prompted that subtracting was just as valid a tactic as adding, essentially everyone ends up adding things.

We’re always defaulting to more, and that, just by itself, is a pretty valuable lesson.

Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry into Values

By: Robert Pirsig

Published: 1974

420 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Advice on how best to care for a motorcycle, wrapped in a new school of philosophy based around the concept of “quality”, wrapped in a retrospective memoir of the author gradually recovering memories from his pre-psychotic-break self, wrapped in a travelog of a cross country motorcycle trip, wrapped in the story of a relationship between father and son.

What's the author's angle?

One gets the sense of terrible importance from the book, that Pirsig is saying “At last, I have solved philosophy!” While at the same time getting the idea that what he’s really doing is trying to make sense of his life, just like everyone else. It’s a weird combination.

Who should read this book?

If you imagine that you’re some kind of completist — to be clear I’m not sure what that even means or how it would be accomplished in this context — then this book is beloved by enough people and widely known enough that you should read it. You might also decide to read it if you have a broad interest in philosophy. Otherwise, I would skip it.

General Thoughts

A friend of mine who grew up Mormon and later left the Church described this as his new spiritual text, and urged me to read it. As is typical of me, I listened to it, quickly. I want to say I did him the honor of only cranking things up to 2x, but I don’t remember for sure.

Having done this I reported back and told him that I thought it was a very interesting book. Also, I quite enjoyed it but it didn’t provide me with any particular epiphanies. He blamed my less than stellar review on the fact that I listened to it, and at 2x no less! He urged me to actually read a physical copy of the book, perhaps with a pen in hand. I agreed that at some point I would do that.

Finally, eight years later, that task finally rose to the top of my to-do list. I re-read it carefully, in physical form, pen in hand. And what do I think of it now? I would have to say my opinion dropped a couple of notches. The motorcycle maintenance part was fantastic and reminded me of Matthew Crawford’s work (see my review of The World Beyond Your Head) and his idea that meaning comes from developing skill with some aspect of the real world.

Pirsig’s relationship to his son was also moving, particularly given that the son was murdered in a mugging gone wrong when he was just 22, five years after the book's publication. In new editions there’s an epilogue where Pirsig talks about it.

His philosophical musings are interesting, but they’re not woven into the story in a seamless fashion, they come in big lecture-like chunks.

The story of his pre-psychotic break self, who he calls Phadreus, ends up being downright annoying, and so strange that it undermines his philosophical authority. I’m sure the book wasn’t helped by the fact that I was reading McGilchrist’s examination of hemispheric differences at the same time. Which made Pirsig’s deep examination into quality seem more like an overactive left hemisphere obsessively chasing the meaning of a specific word. Given that this pursuit ends with him having a psychotic break, I feel like this interpretation is mostly accurate.

I actually don’t have a to-do list I’ve been maintaining for the last eight years. The reason I re-read this book now is that I’m hoping for some reciprocity. I want my friend to read Nick Cave’s Faith, Hope and Carnage (see my review here). Which also features the tragic death of the author’s son, and which is, in every respect, a far superior book to this one.

Finite and Infinite Games

By: James Carse

Published: 1986

160 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

There are at least two kinds of games. One could be called finite, the other infinite.

A finite game is played for the purpose of winning, an infinite game for the purpose of continuing the play.

That’s the quote everyone mentions. As far as what the book is about beyond that it’s hard to say.

What's the author's angle?

Once again it’s hard to say. I guess he’s kind of religious? I didn’t get much of that from the book.

Who should read this book?

I’ve had a lot of people tell me to read this book, so I finally did. It is pretty short, so there’s that. But for me it just seemed like a word salad that appeared deep, but really wasn’t. Personally, I would not recommend the book to anyone.

General Thoughts

As I sat down to write this review I noticed that there’s a blurb from Pirsig on the cover. I was not aware of any connection before reading these two books in such close succession. The Pirsig blurb makes sense, both books seem really deep, but the more you dig the less deep they become.

I had gone into the book thinking that it might be about survival as the highest value. Or that it might be similar to Nonzero (see the previous review). In the end what I got was a collection of opaque aphorisms. Some of them aren’t bad, but even those are more woo than deep.

Finite players play within boundaries; infinite players play with boundaries.

On the other hand some of them are far too long to count as an aphorism and beyond that are just incomprehensible vocabulary vomit. An example taken at random from the book:

The paradox of genius exposes us directly to the dynamic of open reciprocity, for if you are the genius of what you say to me, I am the genius of what I hear you say. What you say originally I can hear only originally. As you surrender the sound on your lips, I surrender the sound in my ear. Each of us has relinquished to the other what has been relinquished to the other.

This does not mean that speech has come to nothing. On the contrary, it has become speech that invites speech. When the genius of speech is abandoned, words are said not originally but repetitively. To repeat words, even our own, is to contain them in their own sound. Veiled speech is that spoken as though we have forgotten we are its originators.

You can see where that seems deep. But is it really? And to the extent that it does have some meaning could it not be said more simply? Maybe just “remember your biases?”

With that advice in mind it’s entirely possible that I’m wrong, that this book is a work of genius and I’m too dumb to grasp that. But if so where are the Carse acolytes? The people who defend his view of the world against other views of the world? Rand, Taleb, Pinker, Yudkowsky, Thiel, Dawkins, Kendi, etc. all have people who will stand up and say the world is this way rather than that way, because this person said so. What way of viewing the world is Carse in favor of and which ways would he be opposed to? And how is this way of viewing the world different from a thousand other “the world is limitless” authors?

As you might have gathered I’m not a fan. For a good examination of what (I think) this book might be about, read Nonzero instead.

Fever Pitch

By: Nick Hornby

Published: 1992

256 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The author’s obsession with Arsenal, a team in England’s Premier League.

What's the author's angle?

It’s a confessional memoir.

Who should read this book?

If you like Nick Hornby, and soccer/football, and/or want an insight into the mind of a true sports obsessive.

General Thoughts

Hornby is the author of numerous books which have been made into movies. There’s About a Boy, High Fidelity, as well as several others, including this book. (Both an English version starring Colin Firth, and an American one starring Jimmy Fallon.) I’ve read many of his books and watched many of his movies, and this one is different. As you might imagine it’s not as tightly plotted as his fictional works. None of our lives are, but I found it enjoyable, though in large part that was because I’ve been interested in the Premier League ever since I found out that Nigel Kennedy was a fanatic Aston Villa supporter back in 1992.

But of course post-Ted Lasso numerous people are football fans. Should you fall into this category then this book might enhance your enjoyment of the game. Though to be clear it’s not really about football in general, or even the Premier League, it really is very focused on one team, Arsenal, and one man’s compulsive fandom of that team

Sun and Steel

By: Yukio Mishima

Published: 1968

108 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

This book could be read a lot of different ways, as memoir, as philosophy, as a glorification of physical beauty. For me it was about finding meaning through suffering.

What's the author's angle?

I’m not sure what the author’s angle is, but as everything these days must have a place in the culture war, most people recommending this book are manosphere adjacent.

Who should read this book?

Books as short as this one seem easier to recommend. And Mishima is a very famous writer — at least in Japan, but he also nearly won the Nobel prize for Literature. If anything in this review strikes your fancy it’s probably worth reading the book, given how short it is (2.5 hours on audible).

General Thoughts

It really is difficult to pin down the book, and I fear I haven’t done a very good job. But perhaps a selection might help. This one is rather long, but I think it encapsulates what I enjoyed about the book:

Two different voices constantly call to us. One comes from within, the other from without. The one from without is one’s daily duty. If the part of the mind that responded to duty corresponded exactly with the voice from within, then one would indeed be supremely happy.

On a May afternoon of unseasonably cold drizzle, I was alone in the dormitory, the firing practice that I had been due to witness having been cancelled on account of the rain. It was chilly there on the plain skirting the foot of Mt. Fuji, more like a winter’s day than early summer.

On such a day, tall city buildings where men worked would be aglow with lights even in the daytime, and the women at home would be knitting by artificial light, or watching the television, perhaps repenting having put the gas fires away too soon. Ordinary bourgeois life held no force sufficiently compelling to drag one out into the chill drizzle without so much as an umbrella.

Unexpectedly, a non-commissioned officer arrived in a jeep to fetch me. The firing practice, he explained, was going ahead despite the rain. The jeep drove steadily along the potholed road across the plain, lurching violently as it went.

Not a soul was in sight on the plain. The jeep climbed a slope down which the rain washed in sheets, and drove down the other side again. Visibility was restricted, the wind gathered strength, and the clumps of grass bowed down before it. From a gap in the hood, the cold rain beat mercilessly on my cheeks.

I was glad that they had come from the plain to fetch me on such a day. It was an emergency duty, a voice summoning me lustily from afar. The feeling of hastily leaving a warm lair in response to a voice calling from across the vast rain-blurred plain had a primitive appeal that I had not savoured for many a day.

I often feel the same call, to leave the safety and security provided by modern conveniences and go out in the wilderness in search of some hard task. I fear I’m not particularly good at it, but I know the savour he’s talking about.

III- Fiction Reviews

Coraline

By: Neil Gaiman

Published: 2002

176 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The adventures of a young girl suddenly enmeshed in a dark and scary parallel world.

Who should read this book?

If you liked the movie Coraline or if you like Gaiman, then you’ll like this book.

General Thoughts

Many years ago, thinking that it was a nice, safe children’s movie, I had my kids watch it, and they still talk about how terrifying it was. As you might imagine the book is less terrifying. And while my memory of the movie is less than perfect it seems that they made some choices with the movie that made it still scarier. In any case, my kids are still mad at me about that.

That aside this book is delightful in the way that all of Gaiman’s YA stuff is. It’s interesting and unique and full of great characters.

IV- Religious Reviews

The Gods Never Left Us

Published: 2017

256 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The continued and ongoing presence of aliens (“gods”), as evidenced by crop circles, UFOs, and the Third Secret of the Fatima.

What's the author's angle?

Von Däniken is the grand master of alien conspiracies, and he really lays it all on the line in this book.

Who should read this book?

If you love crazy conspiracy theories, this is chock full of them. Otherwise I would skip it.

General Thoughts

Many people fall into the failure mode of being far too specific. Von Däniken is definitely one of those people. He confidently asserts that the Third Secret of the Fatima reveals the existence of aliens, and goes to lay out how this explains all actions by popes since that time:

The popes refuse to make the message of Fatima publicly accessible. Period… Since 1960 (at the latest) each one of them knows the truth. Each one of them knows about that contact on October 13, 1917. And each one of them knows that the truth is inexorably approaching. Day for day, year for year. It comes as no surprise to me at all that His Holiness Pope John XXIII (1958–1963), who read the message of Fatima in 1960, died of grief and sorrow. The next pontiff, Pope John Paul V (1963–1978), traveled the world and likely informed all the princes of the different religions about the ETs and the inexorably approaching “Judgment Day of Knowledge.” And here it fits the mold perfectly that the next pope, John Paul I, could no longer bear the untruth and went to pieces.

Even before his election, the future pope had detailed discussions with the nun Lucia—the same Sister Lucia who was the former girl of Fatima. The pope’s brother, Edoardo Luciani, reported that after the conversation with Sister Lucia, his brother (the future pope) had been “completely devastated”. He exercised his difficult office a mere 33 days. There was subsequently speculation that the pope had been murdered, presumably because he had found out about some corrupt dealings in the Vatican’s banking business. And what if things were completely different? After all, the pope knew the truth about Fatima from Sister Lucia. He knew that it had not been the Mother of God who had been revealed there but an extraterrestrial. Did he discuss this fact with high dignitaries? Did he intend to publish it? Was this his death sentence? The fact remains: John Paul I was in office a miserly 33 days. The next pope, John Paul II, exercised his office from 1978 to 2005. He is seen as the Apostle who traveled the world. In each country that he visited he first kissed the ground. A symbolic act? Or did he want to symbolize that this land still belongs to us Earth citizens? Finally, there was Benedict XVI, the first German pope (in office from 2005 to 2013). On February 28, 2013, he retired from his office, which was a unique event in the 1,900-year history of the papacy. The highest Church dignitary, the successor to the Throne of St. Peter, couldn’t be bothered anymore. Oh yes, their Holinesses know what is going on.

This is a remarkably specific narrative of how and why things happened. Particularly given that the Vatican released the Third Secret of the Fatima in 2000. Now perhaps it’s fake, and the true secret is about extraterrestrials and has yet to be revealed, but von Däniken doesn’t even mention this event. Is it because he doesn’t know about what happened in 2000? Or does he consider it so obviously fake that it doesn’t even deserve to be mentioned?

He gives the same treatment to crop circles, Lockheed’s Skunk Works, Aliens who look like humans, and at least a dozen other things.

All of which is to say there are interesting things to say about aliens as potential gods and how they might interact with the earth (continue to watch this space…) but Von Däniken’s efforts are fundamentally ridiculous.

Mere Christianity

By: C. S. Lewis

Published: 1952

228 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

A series of essays read on the radio during World War II designed as introduction and apologia for Christianity. The essays were later edited and compiled into a book.

What's the author's angle?

Lewis was one of Christianity’s staunchest defenders, and, if you don’t count Narnia, this is his best known attempt at doing just that.

Who should read this book?

Given its renown, its length, and the overall importance of Christianity, I would say everyone.

General Thoughts

This was not my first time reading this book, but this time, rather than listening to it I pulled out my physical copy and read that while marking it up. He covers a lot of territory and I very much doubt I can do it justice.

Also I’m the wrong person to offer criticism of the book. I’m a big fan of his argument from morality and his trilemma, and his writing in general.

I will say, even though it’s not written as such it’s much better at delivering profound aphorisms than Finite and Infinite Games. I think my favorite was:

No man knows how bad he is till he has tried very hard to be good.

I, too, have been confused about Pinker's not citing Wright.

He did, once — I have a clear memory that it was in one of his many TED talks, in which he quoted Wright as (humorously) saying "Among the reasons I do not want to United States to go to war with Japan is that they made my minivan". (But I also have a clear memory of looking for this quote, and not finding it, so...!)

Re: ChatGPT's thinking that Pinker would tsk-tsk Wright's eschatological end, I'd wager (but just a bit!) that the transcript of their conversation (some years ago) on Wright's (excellent) podcast was in its training data. Wright thinks that greater and greater intelligence is a consistent theme in evolution, while Pinker thinks that it's not.

...why do I know so much about this? My goodness. What have I been spending my hours on...

From the little bit in your review of Carse, he reminds me of Martin Buber. I would say, subjectively, that Buber is about not winning. I see that in what he's trying to say, and also, his writing doesn't win. I.e., it's hard to pay attention to. Definitely true of Between Man and Man, maybe a little less true of I and Thou. I and Thou is his big book, in continental philosophy form, Between Man and Man covers similar territory in a more concrete way. I think I and Thou is harder to read but easier to try to read, if that makes sense.

Winning authors go in for the kill and get you to be interested or obsessed. I think that Pinker, Yudkowsky, and Dawkins are very much about Winning, and Rand, Thiel, and Taleb may be (don't know much about Kendi). Buber is different. I think Buber is basically good (with my rational and quietly intuitive self), but I find it hard to be obsessed by him. I think that many others are basically bad or at best mixed, but much easier to get obsessed with, and they have more cultural power.

I thought that Buber was a more or less forgotten name, because he didn't come up in the online circles that I've been part of (EA/rationalist, Christian but seemingly mostly Catholic or Calvinist rather than the others.) But someone told me that he's big in the therapy world, and I think he has been big in education and among pastors, not sure if he still is. Those are the Buber fans, and you can see how extending a conversation rather than winning would be their thing. People like them might like or even champion Carse.

Catholics, Calvinists, EAs, rationalists, (the Catholics/Calvinists who get in the same spheres as EAs and rationalists) may all be about society, structure, power, policies, the greater good, culture as a whole, etc. -- a fundamentally impersonal world, in terms of how a person relates to it. Whereas therapists, pastors, and teachers are more into individual people, or relatively small groups of people -- a fundamentally interpersonal world. Nonzero (from your review) sounds like it fits into the Big Impersonal world, while Buber (and maybe Carse) fits into the Small Interpersonal world.