Dalio vs. Zeihan

If you prefer to listen rather than read, this blog is available as a podcast here. Or if you want to listen to just this post:

My last newsletter briefly compared three different visions for the future. The first was laid out by Peter Zeihan in his book The End of the World is Just the Beginning. (See my review here.) Zeihan’s book was in my opinion the most pessimistic of the three, but if all you care about is the US then you might call Zeihan an optimist. Certainly he was more optimistic about the US than the second book, Principles for Dealing with the Changing World Order: Why Nations Succeed and Fail, by Ray Dalio (review here). But Dalio was more optimistic in general. However, the crown for the most optimistic take on the future belongs to David Deutsch and his book The Beginning of Infinity: Explanations That Transform the World (review here) which outlined an optimism for the future which bordered on the religious.

As part of the newsletter I discussed how one might respond to these three very different versions of the future, but I postponed discussing the actual details for another post. This is that post. I plan to spend most of my time on Zeihan and Dalio, but I’ll toss in Deutsch from time to time to liven things up.

Also it’s going to be impossible to avoid repeating some of the things I already said in my review of the books, so for those who read those reviews I apologize in advance for the duplication, but I do hope to spend most of this post comparing and contrasting the various predictions, rather than discussing them individually.

I- Is the US Doomed Or What?

As I already mentioned one of the biggest disagreements between the two authors is their take on the future of US power. Dalio brings a very cyclical view to his analysis, which is to say his approach involves finding patterns in the past and then looking for those patterns in our current situation. And the pattern he sees when he looks at the US is of a nation that has passed his peak and is on the way down.

Zeihan obviously has a very different approach. He’s a geopolitical analyst, so he’s interested in what resources are where. Who trades with whom and why. Where is the food produced and where is it consumed. Natural barriers and what might make conquering a nation easier or harder. It’s hard to tell how he feels about political and culture cycles. He never mentions them in his book, and he only mentions financial cycles once, in the briefest fashion possible. I suspect he would acknowledge the existence of all those cycles, but would argue that they’re overshadowed by questions of geography. Take this quote as an example:

Even the biggest and most badass of all those echo empires—the Romans—“Only” survived for five centuries in the dog-eat-dog world of early history. In contrast, Mesopotamia and Egypt both lasted multiple millennia.

First, I couldn’t figure out what he meant by “echo empire”. But if we get past that he’s basically saying that if you have geography on your side there’s almost no limit to how long your civilization can last. Yes, there will be ups and downs, but underlying all that there will be continuity. You won’t have the dramatic and complete collapse that we saw with Rome. But on the other hand if you don’t have geography it doesn’t matter how “badass” you are, your days are numbered.

This is the source of his optimism about the US. According to Zeihan we have the best geography ever. From this can we assume that Zeihan thinks that the US of A will last for thousands of years? In a similar fashion to Egypt and Mesopotamia? He never explicitly puts a time horizon on the country’s lifespan, but he does assert that whatever our current difficulties are, they will be temporary.

…the United States will largely escape the carnage to come. That probably triggered your BS detector. How can I assert that the United States will waltz through something this tumultuous?

…I understand the reflexive disbelief…Sometimes it feels as though American policy is pasted together from the random thoughts of the four-year-old product of a biker rally tryst between Bernie Sanders and Marjorie Taylor Greene.

My answer? That’s easy: it isn’t about them. It has never been about them. And by “them” I don’t simply mean the unfettered wackadoos of contemporary America’s radicalized Left and Right, I mean America’s political players in general. The 2020s are not the first time the United States has gone through a complete restructuring of its political system. This is round seven for those of you with minds of historical bents. Americans survived and thrived before because their geography is insulated from, while their demographic profile is starkly younger than, the bulk of the world. They will survive and thrive now and into the future for similar reasons. America’s strengths allow her debates to be petty, while those debates barely affect her strengths.

Perhaps the oddest thing of our soon-to-be present is that while the Americans revel in their petty, internal squabbles, they will barely notice that elsewhere the world is ending!!!

Let’s assume that Zeihan is right about all of this, that still doesn’t mean that a “complete restructuring of [our] political system” is going to be pleasant. Presumably, one of the seven times this restructuring happened previously was the Civil War, and yes we did survive, and eventually our thriving continued, but for those that experienced the era that stretched from the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 through the end of Reconstruction in 1877 those debates didn’t seem petty or temporary.

Meaning at a minimum while Zeihan might have good news for my great grandkids, it might still be awful news for my children and grandchildren. But also, we shouldn’t discount the idea that his assessment of American durability powered by geography could in fact be entirely misguided, but I’m getting ahead of myself. What’s interesting is that while Dalio and Zeihan disagree about so much else their short term projections end up being very similar.

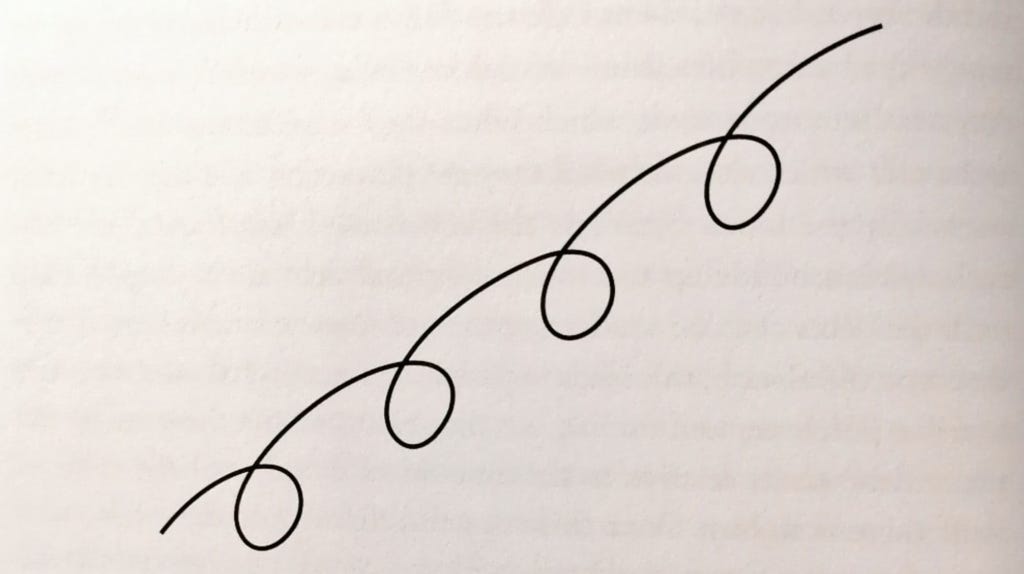

You might remember this graph from my review of Dalio:

Dalio’s assessment is that history moves in an upward sloping corkscrew pattern. It loops up during the good times and down during the bad times, but the overall trend is positive. Dalio believes the US has peaked, but according to Dalio that’s okay because Spain, the Netherlands and the UK have all peaked as well and they’re doing fine at the moment. Sure they’re not the biggest dog on the block anymore, but the average living standard for their citizens is still in the top 20% globally. Similarly, there will be some disruption and bad times as the baton is passed to China, but over the long term things in the US will be comparable to things in the UK. We won’t have the superabundance we had when we were at the top of the heap, but we’ll be fine.

Given that the period all of us are most interested in is the next 20-30 years it should be at least a little bit sobering that both Zeihan and Dalio are saying that this period is going to be bumpy. Sure it’s some comfort that both believe after a couple of decades or so of bumpiness that things are going to be fine. But what if they’re right about the bumpiness, but wrong about the “eventually fine” part? Unfortunately I think there’s good reason to believe that they might be.

The problem, as I see it, is that both of them have decided that a certain period in history, and certain nations from that period can tell us what’s going to happen to the US. That these nations provide an accurate model from which we can draw conclusions. For Dalio it’s recent history because that’s where there’s sufficient data for him to draw some conclusions. As such he’s looking at the UK, and before them the Netherlands, and before them Spain. Those countries were all top dog at one point or another, but he also looks at France and Germany, countries that could have been top dogs. You may be noticing a geographic bias. All of those countries are in Europe. Which is not to say that Dalio didn’t look at non-european countries. But Europe is where the data is best, and where all the recent great powers were located.

I completely understand why he did it, but I still think it’s myopic, and as a further example of myopia, Dalio spends most of his time examining what it looks like for a country to rise and fall and not nearly enough time on the transitions from one country being on top to the next. In particular how the next transition might be different than the previous ones. As I argued in my review, the most recent transitions have been exceptionally mild. Transitioning from the Netherlands to the UK involved two countries separated by a thin stretch of ocean, that at one point had the same king. Transitioning from the UK to the US happened sometime in the early 20th century when both countries were allies in the World Wars, and both spoke the same language. The situation with the US and China is entirely different. If, as Dalio claims, a transition is happening, it seems unlikely to look anything like the previous two reserve currency/economic/cultural/military transitions he spends most of his time on.

So that’s Dalio, what about Zeihan? What point in history and what nations within that period is Zeihan using for his model? He doesn’t place a huge emphasis on it, but I really do think that his example nations are Egypt and Mesopotamia. Spots which were safe for empires for thousands of years. And while I think that’s silly, I also kind of get it. Zeihan makes a powerful case for the US having uniquely amazing geography, but geography isn’t the only factor for long term survival. I mean Egypt and Mesopotamia didn’t survive to the present day. Something ended their thousands of years of stability, and that something was new technology.

The easiest way of illustrating the point is not with either Egypt or Mesopotamia, but with Constantinople. Constantinople lasted a thousand years after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, and it did so essentially because of its geography. It had the “geography” of its immense walls, plus it was a port so supplies and reinforcements could generally be brought in by sea. But at some point the technology was developed to destroy those walls, and that was the end of Constantinople. The US has the walls of the Atlantic and the Pacific, along with the fact that there are no credible competitor nations in North or South America. But the question of whether these “walls” could be breached would appear to be a very important one.

The obvious candidates for such a breach are ICBMs, and as I mentioned both in this most recent review of Zeihan, but also in the review of the book before that, Zeihan seems curiously uninterested in exploring the possible use of nuclear weapons. I’m not necessarily saying that because he ignores nukes that he’s wrong about long term American dominance, there is a fair amount of “nuclear weapons are not that big of a deal” opinions floating around in the internet at the moment. But Zeihan should at least address the issue. He should explain why he’s not concerned about Russia and China using their ICBMs if their “worlds are ending” (see his quote above) and the US is sitting there fat and happy. The fact that he so completely ignores it makes me think I’m missing something. And I will say I did a quick search to see if there was a blog or something where he talks about it, but nothing obvious popped up.

I think Dalio, to a certain extent, also discounts technology. Deutsch, for all the shade I throw on him, at least doesn’t make the mistake of minimizing technology, rather he goes too far in the other direction, and furthermore seems to assume that such technology will be good.

I’ve spent longer than I intended talking about the US, but I do have three final points I’d like to squeeze in, mostly related to Zeihan’s take. First off, just because an area is secure from external threats, and doesn’t need external help doesn’t mean that it’s internally stable. Egypt may have lasted for over 3000 years, but a quick check of Wikipedia shows that during that time there were 31 dynasties with a mean length of 103 years. So what does it really mean for the US to be dominant? That for the foreseeable future North America will be the power base for the world’s most powerful country? Okay, but that says nothing about what sort of country it is, or even whether it’s a great deal for its citizens. Being a powerful country is only loosely correlated with keeping the country’s citizens happy and fulfilled. If you’re interested in preserving American culture, you’d almost have to say that Dalio is more optimistic despite his more pessimistic take for the country as a whole.

Second, Zeihan is very emphatic that we’ve been living through a moment that’s historically unprecedented. I am in total agreement with that, but Zeihan seems to mostly be focused on just one area in which it’s unprecedented: unrestricted, safe global trade. I think it’s unprecedented in at least a dozen other ways which makes predictions of the sort Zeihan is making particularly difficult. Both Zeihan and Dalio seem to think we’re at the end of an incredible historical run. (While Deutsch thinks we’re just at the beginning of one.) But is it possible they’ve misidentified exactly what it is that’s ending? Part of my problem with Dalio is that he’s predicting the decline of the US, but that would also mean the decline of the West, and since so much of his data comes from the West, if it’s also declining his data may be misleading rather than illuminating. Another thing that’s unprecedented is how democratic the US is. When you’re thinking about ancient empires and monarchies a lot of what was going on was churn at the top, while the bulk of the population kept doing what they were doing. These days any churn is going to be society wide. To return to the quote I mentioned earlier, Zeihan asserts that it was never about the political players, but these days everything is political and everyone is a player. What then?

Finally this idea that the US will retreat back to the Americas, and sit there, unperturbed, while the rest of the world descends into wars, famines and diseases seems way too simplistic. But this is precisely what Zeihan is predicting, and on a massive scale. He asserts that once the US withdraws from the world that a billion people will starve to death and two billion will be malnourished. I’m not sure what we would do if this was happening, but I don’t think it would be “nothing!”.

II- Okay What About China? Is it the Next Hegemon or a Demographic Disaster That’s One Sunk Ship Away From Starvation and Collapse?

As I pointed out in my review, Zeihan asserts that “everything we know about modern manufacturing ends” the first time some nation shoots at a “single commercial ship”. I was doubtful it happens on the very first shot, but I agree with Zeihan in general. If commercial ships become fair game for violence we are in a completely different world. But it’s not as if a switch gets flipped, Rather we would enter a time of profound uncertainty. Does this uncertainty play out in the fashion Dalio predicts, with China ending up on top? Or does it play out like Zeihan predicts with China, broken, starving, and malnourished? Or perhaps it never happens at all? Which is I guess what Deutsch would predict. Or is there some way for all three of them to be correct?

There’s a quote from Adam Smith that is appropriate at times like this: “there is a great deal of ruin in a nation”. Meaning that when a nation has built up wealth, institutions, infrastructure and legitimacy over many decades that it takes a lot of disasters, not merely one, to destroy it. The same can be said for the postwar order. I think safe global trade has been engrained for long enough in people that it’s going to take a lot for things to switch back. That’s the sense and really the only sense in which Deutsch is correct. And I’m stretching to give him even that much credit because it is going to switch back at some point. But as long as it hasn’t, Dalio has made some good points, and Zeihan isn’t even in the game yet. Once the switch is flipped from safe to unsafe seas, well then Zeihan is your man, at least for identifying all of the weaknesses. As far as how those weaknesses play out, who knows. Despite how dour Zeihan’s predictions are, it could actually be worse, we could get all the famine he predicts, plus a full on nuclear exchange. My point, however, is that it’s farther out that Zeihan thinks. So as long as the switch hasn’t flipped, what happens with China?

A couple of years ago (almost exactly!) I examined a half dozen or so “takes” on China. Most of them proceed along lines you’re familiar with, with lots of discussion of Taiwan. But one that has always stuck with me is the assessment by Paul Midler. Unless it was from reading my previous posts you’ve probably never heard of Midler. He’s English (or American, I can’t recall for sure) and he’s been working in China for decades. His claim is that the key to understanding the Chinese leadership is to understand that they don’t think in terms of perpetual progress, they think in terms of dynasties. They don’t imagine that conditions 50 years ago were worse than they are today, and that they’ll be better still 50 years hence. Their thinking is more cyclical. Dynasties rise and dynasties fall, and while they’re rising you get what you can, and while they’re falling you hunker down and survive. And according to Midler everything the current leadership is doing is an attempt to get what can be gotten while things are good. And if they do it well enough they might even still be in power when the cycle turns. They’re looking to check off boxes: Recapture Taiwan. Build a lot of stuff. Keep the country free of COVID. Etc.

Looked at through this lens you can start to imagine how both Dalio and Zeihan might be seeing a piece of the elephant. Dalio sees the immense progress. He can see all the graphs going up. And in the past, when that happened in the West it heralded the rise of a new global power. But Dalio is viewing it as someone who expects people to pursue progress for its own sake because of the benefits it provides, not because of the positive PR it gives the leadership. But in contrast to the other countries he’s studied, China is far more of a top down society. Consequently most significant initiatives are driven by the leadership. On the other hand Zeihan sees the immense underlying weaknesses, and knows that things can’t last. But the Chinese leadership is seeing the same thing. Not only are they not blind to it, they expect it. They assume that things are going to come crashing down and they’re desperate to lock in as many accomplishments as they can.

Pulling all of this together, including all of the stuff about the US, what do we end up with? In the near term we end up with an aggressive and achievement focused China butting heads with an America that is in transition. This transition is definitely happening on a lot of fronts but one of the biggest is ceasing to be the globocop. Willingly if you believe Zeihan. Unwillingly if you believe Dalio. But that transition is not going to be smooth (witness Ukraine). While a lot of this comes from the nature of the transition itself, America also seems to be suffering from serious internal problems as well. (Something which Dalio has a chart for, but which Zeihan mostly dismisses.) This makes the timing of this transition unfortunate.

In the medium term, there’s a lot of “ruin” in China, and they’re not going to go down without a fight. If they go down at all, but here’s where Midler’s take is important. I think even the Chinese expect that this is what’s going to happen, that the good times can’t last forever. Where is the US by this point? I think a post hegemonic America, having also passed through whatever chaos awaits us over the next couple of decades, will be significantly different than the America we’re used to and significantly different than what Zeihan is predicting. Though I agree with him that we’ll still be better off than Europe or China, and probably Africa and South America as well, but better doesn’t mean good.

Over the long run? Well that sort of prediction is a suckers game, but to bring our third author in one last time, I guarantee that whatever Deutsch says, we are not at the “beginning of infinity”. We’re at the beginning of several very chaotic decades.

With a post like this, covering so much territory, there’s always a ton of stuff I don’t get to. One observation I had is that each author champions a different reserve currency. Zeihan thinks the dollar will continue in that role. Dalio thinks we’re going to switch to the yuan, and while he doesn’t say it. I peg Deutsch as a bitcoin guy. I don’t particularly care, I’ll take any thing.