The 8 Books I Finished in August

If you prefer to listen rather than read, this blog is available as a podcast here. Or if you want to listen to just this post:

Principles for Dealing with the Changing World Order: Why Nations Succeed and Fail by: Ray Dalio

The Case Against the Sexual Revolution: A New Guide to Sex in the 21st Century by: Louise Perry

The War on the West by: Douglas Murray

The Dumbest Generation Grows Up: From Stupefied Youth to Dangerous Adults by: Mark Bauerlein

Wanting: The Power of Mimetic Desire in Everyday Life by: Luke Burgis

The Giver by: Lois Lowry

The End of Eternity by: Isaac Asimov

Bad Religion: How We Became a Nation of Heretics by: Ross Douthat

At the beginning of July, in this space, I worried that with all the traveling I had coming up that I would get out of the habit of writing. I don’t know that that’s precisely what happened, it was more that I transitioned into a different mode of fitting in my writing, and then had difficulty, upon my return, in transitioning back. Accordingly, you have my apologies that I only got one essay out last month, and none the month before. I hope to make it up to my loyal readers at some point.

Additionally I was working on a very long book review for a magazine. (Ethics of Beauty, you may recall me mentioning it last month.) The magazine is called American Hombre, and the first issue is coming out this month. It’s being done by Erik Taylor, who’s a good friend of mine. You can pre-order it now. (The actual physical magazine will be available in a couple of weeks.)

I’m quite excited about it, and not just because I’ve got a book review in it. I miss the days of the glossy magazines with great pictures and solid content, and this is very much what American Hombre is. It’s a visual magazine, and a throwback to a simpler, and dare I say, better time.

It would mean a lot to me if some of you would check it out, as in purchase a copy of the first issue or better yet subscribe.

The address do that is: https://americanhombre.gumroad.com/ and readers of my blog get a dollar off the price of an issue or 10% off the cost of a subscription, just use the coupon code ‘RW’.

And seriously, go do it, you won’t regret it.

I- Eschatological Reviews

Principles for Dealing with the Changing World Order: Why Nations Succeed and Fail

By: Ray Dalio

Published: 2021

576 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Another cyclical theory of history and nations. Dalio is particularly focused on the role debt plays in that cycle. Given our own massive national debt, Dalio thinks our best days are definitely behind us.

What's the author's angle?

Dalio runs Bridgewater, an investment management firm, and his interest in history initially stemmed from a desire to not lose money. That still informs much of his analysis, but over the years it has broadened into adjacent areas like politics, war, and social unrest.

Who should read this book?

I have issues with Dalio’s optimism, but if you also think America’s best days are behind us, and you want to understand why, this is a fantastic book. It reads well, and some of the charts he includes would make the book worthwhile all by themselves. Also his commentary on China (Chapter 12) seems particularly perceptive.

General Thoughts

The problem with any kind of cyclical analysis whether it be from Dalio or Turchin or Spengler is that your data set is so small. Even if we assume that cycles are a thing there haven’t been very many of them. Plus it’s difficult to imagine that steadily advancing technology wouldn’t alter whatever pattern we did detect. But even without the advance of technology it’s hard to imagine that different nations in different places wouldn’t end up with different behavior. As such it’s difficult to use previous cycles to predict future cycles. Nevertheless, to the extent that it is possible to work within these limitations, Dalio does so in superb fashion.

His book is built around three big forces:

Long-term debt and capital markets cycle

Internal order and disorder cycle

External order and disorder Cycle

As you might imagine from his background Dalio is the strongest and most novel when it comes to the first cycle. But he’s got interesting things to say, and interesting charts, about the other two as well, which he often connects to the financial side of things. Here are a few examples:

He has a list of economic red flags which generally precede revolutions and civil wars. When over 80% of the items on the list are present then the chances of such an internal disturbance in the next 5 years are 1 in 3. When 60-80% of them are red then the chances are 1 in 6. The US is currently in the 60-80% bucket.

Similar to Taleb he points out the historical blindness of most investors. Specifically mentioning that in the 35 years before WWII “virtually all wealth was destroyed or confiscated in most countries, and in some countries many capitalists were killed or imprisoned”. That was not that long ago nor were the circumstances all that different.

He spends quite a bit of time talking about the Dutch Empire of the 17th and 18th Century. As someone who spent two years in the Netherlands on a religious mission, I really appreciated these parts, but it’s a fascinating story that most people are completely unfamiliar with.

As I said I really like his charts, and the charts for China are scary. Not only do all the lines go up for China, while mostly going down for the US, the steepness of those lines is also amazing. The beginning of the cycle for other nations was always pretty gradual. China’s rise looks exponential.

In general the book seems like bad news for the US and good news for China. It makes the case that the US is nearing the end of the cycle and on its way down, while China is at the beginning of the cycle and on its way up. That said, the the US is still #1. The question is how long does it remain in that position and what does transitioning to #2 look like? (Assuming Dalio is correct.) Dalio seems to think that it’d be dumb to go to war over Taiwan, a place most people can’t find on a map. But also acknowledges that the US can’t back down either without completely losing credibility with all of our allies. We have ended up in a no win situation. So that’s our position in the short term, what about the long term?

Eschatological Implications

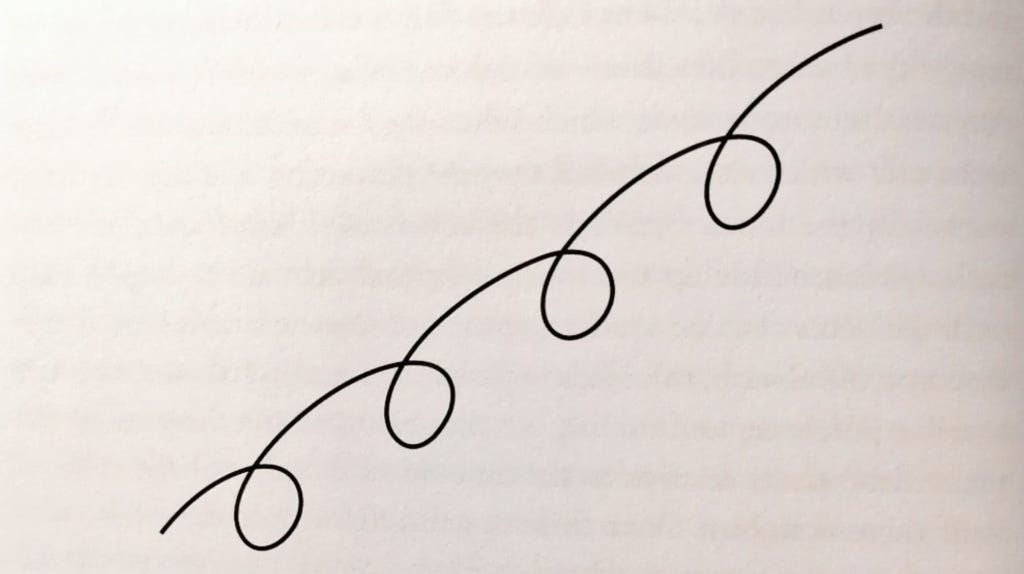

You might think from my description of the book thus far that Dalio is a pessimist, that it’s all doom and gloom. And in the short term that’s a reasonably accurate description of things, but over the long run he’s an optimist. While he thinks that the US is on its way down, overall he views history as moving in a corkscrew pattern. It loops up and down, but the overall slope is positive—that because of human innovation there is an arc of history and it points upward.

He also mentions that while bad periods are bad (by definition) that they’re not as bad as people imagine:

What are these destruction/reconstruction periods like for the people who experience them? Since you haven’t been through one of these and the stories about them are very scary, the prospect of being in one is very scary to most people. It is true that these destruction/reconstruction periods have produced tremendous human suffering both financially and, more importantly, in lost or damaged human lives. Like the coronavirus experience, what each of these destruction/reconstruction periods has meant and will mean for each person depends on each person’s own experiences, with the broader deep destruction periods damaging the most people. While the consequences are worse for some people, virtually no one escapes the damage. Still, history has shown us that typically the majority of people stay employed in the depressions, are unharmed in the shooting wars, and survive the natural disasters.

As you might have noticed he labels these times as destruction/reconstruction periods. Pointing out that while bad things happen good things later emerge. This doesn’t merely include times like the Great Depression it also includes all of the wars which have been fought as well.

But of course we haven’t had any wars recently, and the economic troubles we’ve had have been pretty mild as well (largely due to government intervention). We seem to be pushing the destructive period out as far as we can, which inclines one to believe that when it finally arrives it will be particularly bad.

And this is the big problem with his rosy view of the future. He spends a lot of time considering how this cycle will be the same as past cycles but almost no time considering how it will be different. Let’s review his three cycles:

1- Long-term debt and capital markets cycle:

Has any country's debt reached the size of the US’s? Or been as critical to the world economy? What about the centrality of the dollar as the world’s reserve currency? Or the size of US financial markets as a percentage of all economic activity? Dalio compares the ascendent US to similar periods for the Netherlands and the UK. How central do you think the guilder, and the Amsterdam stock market were to the entire world at the height of the Dutch Empire, in 1700? I’m sure they were important, but there’s no way they were important on the scale of the dollar and the US financial markets in 2000. What about the UK in 1850? Here we come a little bit closer, but even so I think we’re still talking about a much smaller scale, with far less interdependence. And when things did start to collapse for the UK after WWII, the US did a lot to soften things. Do you imagine China will provide the same courtesy to us when our turn arrives?

2- Internal order and disorder cycle

Not only is the US a lot bigger than the Netherlands and the UK, as I pointed out in a previous post: American problems have ended up being problems for the entire Western world. Additionally, out of all the elements Dalio discusses I feel like internal disorder is the one most subject to variation, not necessarily happening at the same point in the cycle or in the same way. Consequently it’s difficult to say if the internal disorder happening in the US will end up being relatively mild or if it will devolve into full on civil war. But it already feels like it’s going to be worse than what was experienced by the Dutch and English at their decline.

3- External order and disorder Cycle

This last item is where the biggest differences lie in my opinion. For one thing the last two transitions were relatively smooth—far smoother than we can expect the transition from the US to China to be. The accession of William of Orange to the throne of England created an obvious link between the UK and the Netherlands, and made it easy for the financial happenings in Amsterdam to move to London. Yes, later the two nations did fight a war, but it was so inconsequential you’ve probably never heard of it. As to the next transition it’s hard to imagine that moving from the UK to the US could have been made any smoother. Yes, obviously the World Wars have to be included as part of that transition, but the two countries were allies for crying out loud. The wars took place because Germany was also a contender for the next great power, and in essence the UK decided it would rather pass the baton to the US than have it forcibly taken by the Germans. But this time around there isn’t going to be any peaceful baton passing, it will have to be taken by force. And force has taken on an entirely new character since then. In other words we have nukes.

I think Dalio makes a pretty convincing case that the US’s time in the sun is coming to an end, I am less convinced that this end will be similar to previous declines and ascents. I think the ways in which it is different and potentially worse are far greater than the ways in which it’s similar.

The Case Against the Sexual Revolution: A New Guide to Sex in the 21st Century

by: Louise Perry

Published: 2022

200 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

That men and women have very different preferences when it comes to sexual behaviors, and that the sexual revolution, and sex positive feminism, rather than prioritizing the preferences of women, have instead entirely surrendered to male desires and inclinations on subjects like what sex should be like, when it should happen, what commitments it entails, etc.

What's the author's angle?

Perry is heavily involved in a group over in the UK called We Can’t Consent To This, which works to eliminate “rough sex” as a defense option for men who have murdered their female partners. The deaths of at least 60 UK women have been excused in this fashion, which represents the tip of the spear for problems of “consent” enabled sexual violence.

Who should read this book?

I really enjoyed this book. But if you’re familiar with my biases that should hardly be surprising. Still if you’re someone who’s had doubts about whether “consent” can act as the entire foundation for which sex is good and which sex is bad, then you should definitely read this book.

General Thoughts

For those of you who caught my last post, you might remember that I mentioned this book in conjunction with previous taboos against premarital sex. Obviously I was referencing her in support of a fairly conservative position, and lest you mistake my position for her position she does state, fairly early on in the book, that:

…although I am writing against a conservative narrative of the post-1960s era, and in particular those conservatives who are silly enough to think that returning to the 1950s is either possible or desirable, I am writing in a more deliberate and focused way against a liberal narrative of sexual liberation which I think is not only wrong but also harmful.

Though lest you think I distorted her position, this is what she had to say about marriage:

The task for practically minded feminists, then, is to deter men from cad mode. Our current sexual culture does not do that, but it could. In order to change the incentive structure, we would need a technology that discourages short-termism in male sexual behaviour, protects the economic interests of mothers, and creates a stable environment for the raising of children. And we do already have such a technology, even if it is old, clunky and prone to periodic failure. It’s called monogamous marriage.

I couldn’t have said it better myself, but what is this idea of “cad mode”?

Perry says that men have two modes: cad mode and dad mode. Now of course this is a continuum, not every man is either a perfect dad or a perfect cad. And more importantly incentives can change someone into more of a dad or more of a cad. There are still men that will respond to their partner’s pregnancy by dispensing with all of their caddishness and fully becoming a dad. But of course there are also men who, in a previous age, would have married their partner and become dad’s who now, because of modern incentives, abandon her and move on.

While Perry’s book ends with a full throated defense of monogamous marriage, the bulk of the book is taken up by an examination of these incentives, and how sex positive feminists have participated in enabling maximum caddishness, or as Perry puts it:

…a long, sorry history of feminists prioritising their own intellectual masturbation over their obligation to defend the interests of women and girls.

Of course what you’re looking for now are specific examples. There are many. Perry covers a lot of ground and I ended up with 94 highlights. I can’t possibly cover even a fraction of the excellent points she made. So I’ll just focus on one extreme example: choking. Be warned this gets graphic.

Sexual liberation has advanced far enough in the decades since it began that very few things are off limits, if there’s consent. One of those things that consent has made possible is sadism. (Perry has a whole section where she discusses the Marquis de Sade.) Consent is the magic spell that changes, pain, humiliation, degradation, and domination from bad things into good things. Specific examples of these “good things” include slapping women, strangling them with belts, and scarring their back with razor blades.

The most fashionable thing at the moment is strangulation, which is not only ubiquitous when it comes to pornography, but extremely common outside of it as well. Perry provides statistics showing that over half of 18-24 year old women in the UK report being strangled by their partners during sex. Many said that it was unwelcome and frightening, while others reported they had consented, and a few said they had invited it.

Herein lies the crux of the problem of consent. There’s the outer circle of women who consented to sex, but once it’s going on it was impractical to try to consent to everything that happened. Then there’s a smaller circle of women who did consent, but once again consent in the moment when things are already moving quickly is different from fully informed consent without any expectations or pressure. And then there’s finally the smallest circle which is women who invited it.

Even if we take this smallest circle at their word, and assume they really enjoy it, they seem to be enabling the strangulation of all the people who don’t really enjoy it and the people who think it’s frightening. To put it another way, in order to make it available to the 5% of women who really enjoy it, do we inevitably end up with it happening as well to another 45% who have to suffer through it?

And is it actually 5%? Could it be 1%? Could it actually be 0%? If we assume that women enjoy this sort of thing then one would imagine that they would enjoy it even with no man present, and yet, as Perry reports:

But a fetish for strangling oneself is vanishingly rare among women, so much so that I have not been able to find a single case in the UK of a woman accidentally killing herself during an auto-erotic asphyxiation attempt gone wrong, with the notable exception of 21-year-old Hope Barden, who died in 2019, having been paid to hang herself on webcam by Jerome Danger, a sexual sadist obsessed with extreme porn.

So how many women are really, truly consenting to this inherently dangerous practice? (Perry includes studies that say that there is no safe amount of strangulation.) On top of all the foregoing the bit about truly consenting is troublesome as well. Perry provides plenty of examples of porn stars who, while deep in the business, will go on and on about how they not only consent to everything, but that it’s an expression of their deepest desires. Only to later, once they’re out, vociferously claim that it was horrible, degrading, and except for the fact that they needed the money they wouldn’t have consented to any of it.

On that note we’ll wrap up with a final selection from the book.

Taking a woman at her word when she says ‘of course I’m consenting’ is appealing because it’s easy. It doesn’t require us to look too closely at the reality of the porn industry or to think too deeply about the extent to which we are all – whether as a consequence of youth, or trauma, or credulousness, or some murky combination of all three – capable of hurting or even destroying ourselves. You can do terrible and lasting harm to a ‘consenting adult’ who is begging you for more.

And the liberal feminist appeal to consent isn’t good enough. It cannot account for the ways in which the sexuality of impressionable young people can be warped by porn or other forms of cultural influence. It cannot convincingly explain why a woman who hurts herself should be understood as mentally ill, but a woman who asks her partner to hurt her is apparently exercising her sexual agency. Above all, the liberal feminist faith in consent relies on a fundamentally false premise: that who we are in the bedroom is different from who we are outside of it.

Eschatological Implications

This review is already running long, so I don’t want to spend too much more time on things. But as eschatology (at least in the expanded way I use the word) is all about endings, it’s interesting to reflect on things that have already ended, and consider what the consequences have been.

Perry spends quite a bit of time considering the impact of the Pill, and how it ended thousands of years of sex having consequences.

In Sophocles’ Antigone – a play particularly attentive to the duty and suffering of women – the chorus sing that ‘nothing that is vast enters into the life of mortals without a curse.’ The societal impact of the Pill was vast and, two generations on, we haven’t yet fully understood both its blessing and its curse.

…

But the sexual revolution of the 1960s stuck, and its ideology is now the ideological sea we swim in – so normalised that we can hardly see it for what it is. It was able to persist because of the arrival, for the first time in the history of the world, of reliable contraception and, in particular, forms of contraception that women could take charge of themselves, such as the Pill, the diaphragm, and subsequent improvements on the technology, such as the intrauterine device (IUD). Thus, at the end of the 1960s, an entirely new creature arrived in the world: the apparently fertile young woman whose fertility had in fact been put on hold. She changed everything

The question this and the rest of the book raises, whether we’re talking about the Pill, or the collapse of traditional marriage, or pornography, is how do we put the genie back in the bottle?

At first glance it seems impossible, and perhaps it is, but Perry suggests that it’s worth a shot, and I agree. At a minimum it’s worth digging into what the genie has been up to, which I think is a useful way of describing Perry’s book. And as she points out, it hasn’t been good.

II- Capsule Reviews

The War on the West

By: Douglas Murray

Published: 2022

320 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Examples of recent and extreme animosity exhibited against historical western culture.

What’s the author’s angle?

Douglas Murray has been on this beat for awhile. The numerous accusations which have been leveled against him by his enemies are too numerous to mention here. (Check out his Wikipedia page if you’re curious.) Which is to say if you’re looking for a reason to dismiss him you probably won’t have to look very far. I don’t think it’s appropriate to dismiss him, I’m just saying it’s easy.

Who should read this book?

As I mentioned in a previous post, I’m hoping that this book will be looked back on as a chronicle of peak involution. If it truly represents the peak then perhaps you don’t need to read it, but if things haven’t peaked then you definitely should read it in order that you might be informed enough to play some small part in making sure that peak comes soon.

General Thoughts

I’ve already spent a lot of time talking about this book in the post I just mentioned, so it’s not my intent to go deeper, but I would like to relate one story. Yes, it’s an anecdote, and not data, and, yes, this is a book full of anecdotes, but light on data, but there’s a visceral component to this problem that can only be illustrated by looking at specific instances of cancellation/censorship/removal. With that in mind I’d like to tell you the story of Rex Whistler and the mural he painted.

Rex was enormously talented and only 21 when he was chosen to paint a gigantic mural in the refreshment room (later restaurant) of London’s Tate Gallery. The job took him 18 months of exceptionally difficult labor. The mural was a fantasy piece depicting an imaginary land. Everyone loved it. George Bernard Shaw spoke at the opening. It was a triumph.

That very winter the Thames flooded and the painting was essentially destroyed to a height of eight feet above the floor. Whistler once again set to work, and repainted everything that had been destroyed, which was most of it.

Turning it over to Murray for the moment:

I have always found there to be something deeply touching about the character as well as the work of Rex Whistler. He was astoundingly talented, had more technical ability than almost anyone of his generation, and possessed an invention and ease that made everything he painted instantly recognizable. He was also loved by everyone who knew him or even just met him—men and women alike. He worked exceptionally hard at his vocation, had a number of unreciprocated passions for women from a different social class than his own, and was just beginning to master the art of oil painting when World War II broke out.

Perhaps you can guess what happened next. He immediately signed up, spent the rest of his short life in the army and died in Normandy.

For nearly 80 years no one remarked on the mural except to compliment it, but then in 2018 a single Instagram account started complaining about some parts of the mural, claiming that they were racially insensitive. Two scenes were identified, each a couple of inches high, and because of them the restaurant containing the mural has yet to reopen from the pandemic. Thankfully it looks like the mural will not be removed (at least not yet) but a new piece of art needs to be commissioned to be put next to it.

Murray describes worse crimes, but I’m not sure he described anything else that was quite so moronic.

The Dumbest Generation Grows Up: From Stupefied Youth to Dangerous Adults

by: Mark Bauerlein

Published: 2022

256 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

All the ways in which we have abjectly failed the Millenials and Gen Z.

What’s the author’s angle?

Bauerlein is an English professor who presumably has witnessed much of what he describes first hand. This role also explains his diagnosis…

Who should read this book?

This is another in the “Everything’s going to Hell” genre, and I’m not sure it has much to add to the subject. There were several points where I considered abandoning it, but I have a soft spot for people who think that reading will solve all of our problems.

General Thoughts

In a sense Bauerlein is a disciple of Marshall McLuhan, though he never mentions him by name. His argument is that now that kids have gone from reading great works of literature to media that is shallow and superficial, that they have, themselves, become shallow and superficial. They lack the complex understanding and sympathies that people derive from great literature and are instead completely at the mercy of simplistic and memetically driven emotions. Speaking of which…

Wanting: The Power of Mimetic Desire in Everyday Life

By: Luke Burgis

Published: 2021

304 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

A popular, non-academic examination of the ideas of René Girard.

What’s the author’s angle?

Apparently understanding “mimetic desire” turned Burgis’ life around and saved him from unhappiness as a startup slave. Also apparently he’s tight with Peter Thiel the best known disciple of Girardism.

Who should read this book?

I wasn’t particularly impressed by the book. I read it for a book club, and might not have finished it otherwise. I didn’t find it to be particularly revelatory, and rather than making me excited to read one of Girard’s actual books (something that has been on my list for a long time) it actually made me less eager.

General Thoughts

For me the book had two main failings:

First, the whole concept of mimetic desire seemed to be a restatement of Jeff Hawkins Memory-predicton framework. The former seems to be saying that we are constantly examining our surroundings for models of how to behave, while the latter claims that the brain largely operates by building predictive models and then testing those models via observation. There’s not a lot of daylight between those two ideas. Though to the extent that Girard was first I guess he deserves some credit, but the same cannot be said for Burgis.

Second, to the extent that Girard does have a unique insight it revolves around the mechanism of scapegoating. Burgis talks about this phenomenon, but it’s never clear what we’re supposed to take from his discussion. Perhaps I’m being too demanding, but it seems that, at a minimum, a book like this needs to do one of three things:

Explain how the modern world is broken because modernity has perverted or ignored the principle. For example: "Nietzsche was correct, we have flipped the scapegoating mechanism on its head and brought chaos out of order, and that's why things are falling apart."

Show how the modern world is better than the past, perhaps because we have finally internalized scapegoating: "At last we have reached the full flowerings of what Christianity started two thousand years ago where we honor the scapegoat/victim rather than stone them."

Or explain how the modern world is no different than the past. "We still scapegoat, in the same fashion as our ancestors and if we understand more why they did it we can understand why we do it."

Burgis does none of these things, and as a result, while he provides some interesting ideas, he doesn’t do anything to explain how those ideas should fit in with what’s already going on.

All of which is to say that the book was fine, perhaps even good, but it wasn’t groundbreaking.

The Giver

by: Lois Lowry

Published: 1993

240 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Jonas, upon turning 12, is selected to take a special role in his community, one which will rip apart all his comfortable assumptions to reveal the horrible dystopia they all inhabit.

Who should read this book?

I get the impression that people younger than me probably already have read this book, probably in high school. If you have I don’t know that I would recommend revisiting it, and if you haven’t it’s okay, but there are lots better YA books. And even YA dystopias.

General Thoughts

There are two ways to write dystopias. The first is to imagine and present a fully realized world, where, ideally, all the parts make sense. Perhaps you’re not entirely sure how we would ever get there from here, but once the society is established, it’s not obviously impossible. The second way is to work in allegory. The first is common enough that I doubt you need examples, the second is rarer, and can be found most often in shorter works. TV shows like Twilight Zone and Black Mirror, or stories like Harrison Bergeron by Kurt Vonnegut, or The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas by Ursula Le Guin. I mention the latter because The Giver essentially duplicates the plot, which is not to say that Lowry is a plagiarist. I bring it up because I want to compare the allegorical approach to the fully realized approach.

If you’re working in allegory you don’t have to explain how the dystopia persists, you don’t need to explain the mechanisms of how it works, or what the broader world is like. To compensate for these advantages there are obvious disadvantages to using allegories. They’re easier to dismiss, they overlook what Hannah Arendt described as the banality of evil in favor of flashy sin.

But if you just want to pass along a moral lesson an allegory would seem to be the way to go. Unfortunately Lowry seems to want to have it both ways. She puts a lot of effort in creating a fully realized world, but then when the climax of the story arrives she largely abandons this reality in order to dispense her message. It’s an okay message, but I was so distracted by the sudden ridiculousness of the world that I kind of didn’t care about the message.

It is possible it’s just me. I have a long standing obsession with fragility, and the world of the Giver is obviously incredibly fragile. You see no reason why the society has continued as long as it has. Jonas doesn’t rebel because of some special circumstances, or some unique situation. In fact you’re left with the impression that it would be almost impossible not to rebel and screw up the system if you just assume that the society is operating normally.

In other words while the ending was entirely believable, the fact that the same thing hadn’t happened already a hundred times previously wasn’t.

The End of Eternity

by: Isaac Asimov

Published: 1955

191 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The Eternals, a group of time travelers who keep bad things from happening anywhen in the universe.

Who should read this book?

Everyone, including me, should read more old science fiction. And this is a pretty good example of it.

General Thoughts

I’ve never been particularly impressed with Asimov’s characters, and while he might be doing a little bit better than average in this book, none of them are going to knock your socks off. Where he excels is his plots, and this is a great one. You might end up thinking it’s derivative, but only because you’ve read and seen lots of stuff that was actually copied from this book, rather than the other way around.

III- Religious Reviews

Bad Religion: How We Became a Nation of Heretics

by: Ross Douthat

Published: 2012

337 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

A history of religion from the end of WWII down to the present day (or at least 2012 when the book was written).

What’s the author’s angle?

Douthat is a devout Catholic, so he definitely has a dog in the fight.

Who should read this book?

I can’t get enough of Douthat. I’ve never read anything of his that I didn’t enjoy. I was particularly interested in how amazingly religious the country was in the immediate aftermath of the war. It’s always interesting how blind we can be about even time periods relatively close to our own.

General Thoughts

This post is already huge, and I’m hoping to publish it shortly. So I will just say that Douthat does a great job of appearing to be a disinterested observer despite being devoutly religious. As such I think his history of modern American Christianity is particularly useful and compelling, and that is the case whether or not you yourself believe.

I’m not sure if it’s good or bad that five of the eight books were published this year or last. I guess as my readers you might want to know about the latest stuff. But it’s also true that the “latest stuff” will be completely forgotten 10 years from now. If you like getting the lowdown on recent books, or if you have no opinion, or if you hate it, but appreciate my candor, consider donating.