The 12 Books I Finished in January

If you prefer to listen rather than read, this blog is available as a podcast here. Or if you want to listen to just this post:

Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty by: Patrick Radden Keefe

Viral: The Search for the Origin of COVID-19 by: Matt Ridley and Alina Chan

Exact Thinking in Demented Times: The Vienna Circle and the Epic Quest for the Foundations of Science by: Karl Sigmund

Expeditionary Force by: Craig Alanson

Columbus Day (Expeditionary Force #1) by: Craig Alanson

SpecOps (Expeditionary Force #2) by: Craig Alanson

Paradise (Expeditionary Force #3) by: Craig Alanson

Row Daily, Breathe Deeper, Live Better: A Guide to Moderate Exercise by: Dustin Ordway

Indistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your Life by: Nir Eyal

What is a p-value anyway? 34 Stories to Help You Actually Understand Statistics by: Andrew Vickers

The Least of Us: True Tales of America and Hope in the Time of Fentanyl and Meth by: Sam Quinones

Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History by: S. C. Gwynne

Heart: The City Beneath by: Grant Howitt and Christopher Taylor

As you can see I read more than the average number of books this month. I was supposed to go on a mini vacation to Vegas with a friend, but a couple of days beforehand he came down with COVID and consequently they wouldn’t let him out of Canada. As such I had some extra time on my hands.

This is not the most books I’ve ever finished in a month, but it is the second most. As such I’m going to try and keep both the intro and the reviews short.

I- Eschatological Reviews

Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty

560 Pages

Briefly, what was this book about?

The history of the Sackler family, their philanthropy, their wealth, but mostly the radical changes they made to pharmaceutical marketing.

Who should read this book?

If you don’t feel that you’re angry enough about the Sackler’s role in the opioid crisis, and you want to be angrier, this is the book for you. Beyond that it’s a fascinating book about the history of selling drugs, and how Arthur Sackler, the oldest brother in the Sackler clan, changed it forever. That part will also make you angry.

General Thoughts

It has been said that “Behind every great fortune there is a crime.” I’m inclined to believe that this is not true in all cases, but it’s definitely more true than fans of Ayn Rand would have you believe. Regardless of whether it’s true in general, it is definitely true in the case of the Sackler fortune. The Sacklers were the owners of Purdue Pharma, and Purdue Pharma had/has essentially one product: OxyContin. Perhaps you know the crime of which I’m speaking? This crime—kickstarting the opioid crisis—which might plausibly encompass the deaths of hundreds of thousands, is made all the worse by the fact that thus far the Sacklers have entirely escaped any sort of liability or punishment. At least Bernie Madoff went to jail for his crimes, which were less severe by basically any measure.

Should I make this point to certain friends of mine, they would say that the reason Madoff was punished, while the Sacklers will probably escape punishment, is that Madoff took money from rich people, while the Sacklers just killed poor people. And that this is the case because of the wickedness of capitalism. I would probably argue that there’s more to the disparity than that, but I will say that capitalism does not come out of this book looking good. And neither does the FDA, Rudy Giuliani, McKinsey, or high-powered attorneys.

Beyond the story of the Sacklers, which is truly appalling, there’s the story of corruption more broadly. There’s a good argument to be made that the crisis would not have been nearly as bad if a sympathetic FDA official (who later went to work for Purdue) hadn’t let the Sacklers turn the insert for OxyContin into essentially a marketing brochure. One which included the infamous line, “Delayed absorption as provided by OxyContin tablets is believed to reduce the abuse liability of a drug.” A line which the Purdue sales reps spun into the idea that prescribing the drug was nearly risk free.

I could go on listing crimes and corruption, but I’m planning on taking this book and The Least of Us (also reviewed in this post) and maybe one other book, if I find one that looks good, and doing a post on the current state of the drug crisis.

Eschatological Implications

Going into the book I had heard that of the three Sackler brothers and their descendents, only two of the branches were involved with Purdue, and that the descendents of Arthur Sackler were upset because despite having no involvement they too had been caught up in the scandal. Before reading the book this seemed obviously unfair, why should Arthur’s descendents suffer for what their uncles and cousins did?

After reading the book, I would agree that there’s probably still a little bit of unfairness in play, but less than you would think, because the success of OxyContin was entirely based on techniques of pharmaceutical marketing that had been pioneered by Arthur. As one of his employees said, “When it came to the marketing of pharmaceuticals, Arthur invented the wheel.”

What was this wheel? Arthur weaponized science in the service of marketing. And as a byproduct he probably permanently perverted science as well. This great innovation would later be applied to OxyContin, but it was initially applied to Valium. Valium was said to be a mild tranquilizer, completely without any potential for addiction, so safe that it could be given to children, and useful for just about anything. In fact, according to the book, it was prescribed for “such a comical range of conditions that one physician, writing about Valium in a medical journal, asked, ‘When do we not use this drug?’” All of this was a reflection of Arthur’s ability to bend “science” into saying exactly what the marketing needed it to say. In particular it needed to show that Valium was safe. That if it was used properly people wouldn’t become addicted. Decades later Arthur’s brothers and their descendents would be making the same claims about OxyContin. It’s scary how much the debate about Valium is nearly identical to the debate decades later about Oxycontin. From the book:

Even so, there were actual cases, increasingly, of real consumers becoming hopelessly dependent on tranquilizers. Confronted with this sort of evidence, Roche offered a different interpretation: while it might be true that some patients appeared to be abusing Librium and Valium, these were people who were using the drug in a nontherapeutic manner. Some individuals just have addictive personalities and are prone to abuse any substance you make available to them. This attitude was typical in the pharmaceutical industry: it’s not the drugs that are bad; it’s the people who abuse them. “There are some people who just get addicted to things—almost anything. I read the other day about a man who died from drinking too many cola drinks,” Frank Berger, who was president of Wallace Laboratories, the maker of Miltown, told Vogue. “In spite of all the horror stories you read in the media, addiction to tranquilizers occurs very rarely.” In 1957, a syndicated ask-the-doctor column that appeared in a Pittsburgh newspaper wondered whether “patients become addicted to tranquilizers.” The answer assured readers that contrary to any fears they might harbor, “the use of tranquilizers is not making us a nation of drug addicts.” The newspaper identified the author of this particular piece of advice as “Dr. Mortimer D. Sackler.”

Mortimer was Arthur’s brother.

This general idea of science being weaponized is an enormous subject, which is right in the center of the debates being had about the pandemic, and it is to do it a severe injustice to treat it so briefly. But it’s one of the huge tragedies of our current situation that we had such high hopes for science, that by doing it correctly it would save us from making the tragic mistakes of the past. Instead, it proved far too easy to misuse, and ended up empowering a whole new class of tragedies.

II- Capsule Reviews

Viral: The Search for the Origin of COVID-19

by: Matt Ridley and Alina Chan

416 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Investigative journalism into the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic, which ends up concluding that it was most likely a lab leak.

Who should read this book?

Anyone who is curious about the origin of the pandemic, or who, more importantly, is interested in preventing future pandemics.

General Thoughts

I already covered this book in my pandemic retrospective, as such I’ll only briefly discuss it here. In fact this is a good opportunity to have something of a meta discussion about the role of books like these.

To start with, imagine that you’re pursuing a PhD in philosophy, and you have selected Greek Metaphysics as your dissertation topic. In this scenario it’s unimaginable that you wouldn’t read everything Plato and Aristotle had ever written. Should it ever come out that you hadn’t, people would immediately stop taking you or your dissertation seriously.

It’s completely understandable for this standard to be applied at the highest levels of academia, but to what extent should we apply that standard to commentary more broadly? Certainly if someone was going to do their dissertation on the origins of the pandemic we would have good reason to believe that they would read this book, in the same fashion that a philosophy PhD is expected to read Aristotle. But what if they just want to tweet about the origins of COVID? Should we ignore such tweets unless we have good reason to believe that they read this book first?

I think there’s various ways of answering that question, but for me the primary standard would be to consider the importance of the topic. You can imagine that opining about Kim Kardashian’s latest divorce should not require the same level of familiarity with “the literature” as claiming that Russia will definitely not invade Ukraine, or that COVID indisputably had a zoonotic origin.

However, this standard of importance presents a problem. The more important something is, the more people feel that offering their opinion is not only a right, it’s a necessity. But what is this opinion based on? How strong should that foundation be before it’s worthwhile for someone to add their own spin on it?

This takes us to a second standard. I think before commenting you need to have a sense of what sort of fight you’re taking sides in. To get more concrete, I don’t think you necessarily have to read Viral before commenting on the lab leak, but it’d be nice if you had read a review of Viral, or something which fairly presented the argument it was making. Presumably, not having read the book yourself, your own comments would not stray very far from the condensed information you found in the review. For example, you’re allowed to disparage the lab leak hypothesis if you’ve read a review of Viral which presents a credible argument against the hypothesis, and you can fairly represent that argument. This is certainly not as good as reading the book yourself, but I would say it’s definitely a level at which comments are allowed.

Down still further is the standard picking a set of authorities and just parroting their comments. The problem here is that if the authorities have read all the books, they would have read Viral and they wouldn’t be in this category, they’d be in the previous category. Also the ideological fractures which appear to have penetrated every nook and cranny of our world makes finding true authorities, people who are genuinely unbiased and objective, and trusting them that much harder. And remember we’re not talking about what you should believe personally, we're talking about what you’re trying to convince others of. We’re talking about commenting and opining on the issue. In that respect I think we’ve crossed the line, at this point you shouldn’t be commenting. That at most you should be linking or retweeting these authorities, but that you are too far removed from the actual debate to get to weigh in.

I could go on, but I’ve already spent a lot of space in this review not talking about the book. So to return to that, my point is much the same now as it was in my previous post. The origin of COVID is an enormously complicated, but also an enormously important subject, and it deserves the most informed discussion possible, rather than being dismissed out of hand. This is a great book if you want to be informed enough to participate in that discussion.

Exact Thinking in Demented Times: The Vienna Circle and the Epic Quest for the Foundations of Science

by: Karl Sigmund

480 Pages

Briefly, what was this book about?

The Vienna Circle, which ends up being at the center of modern philosophy. The list of names in the circle’s orbit includes Einstein, Gödel, Mach, Boltzmann, Popper, and Wittgenstein, and those are just the ones you might have heard of. There are many more who are only slightly less impressive.

Who should read this book?

I think anyone who enjoys great history would love this book. It’s very well written. It’s also interesting for its insights into philosophy, ideology, math, politics and the interwar period.

General Thoughts

Several years ago I read The World of Yesterday by Stefan Zweig, which was all about Vienna before World War II and during the interwar period. I remember being struck by the difference between Vienna before the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and Vienna after. But Zweig was mostly talking about literature and culture. From Exact Thinking I discovered that Vienna still had a lot of math and philosophy magic left in it during the interwar years—that is until the Anschluss, which spelled the final doom of what was once one of the premier cities in Europe.

Sigmund ends up being the perfect person to chronicle the Circle. He got his PhD in Vienna in the late 60s which was still close enough to the time of the events that he knew quite a few people from the era, who could give him first hand accounts. After getting his PhD he was only away from Vienna for six years before he returned as a professor. As a consequence of his close association with the people and the place his familiarity with the subject is very apparent. This is one of the better history books I’ve read, and there’s so much else in it about the development of math and philosophy that you’re really getting a lot for the time invested in reading it.

Of course as interesting as the Vienna Circle was its brand of philosophy, logical positivism, is basically dead and buried. Karl Popper takes credit for killing it, though I’m pretty sure it wouldn’t have survived even without his intervention. And it’s the same problem we see over and over again, starting with Plato and probably going all the way down to the current rationalist movement. Science and rationality end up being unable to carry all of the ambitions people place upon them. We saw this in Plato and we saw it in the Vienna Circle. (Who incidentally mostly hated Plato, while loving Wittgenstein.) And when those ambitions eventually grow too heavy, they end up crushing the foundation, no matter how much science was poured into it.

Expeditionary Force

By: Craig Alanson

305 Pages

277 Pages

283 Pages

Briefly, what is this series about?

Military science fiction about humanity suddenly discovering that the galaxy is full of super powerful warring aliens, and their attempts to avoid being collateral damage in those wars.

Who should read this book?

If you like pulpy, kind of silly military sci fi, I think you'll really like this series. (At least the three books I’ve read so far.)

General Thoughts

Something about this series reminds me of Inherit the Stars by James P. Hogan. The premise of that book was that in the near future we find a dead guy in a spacesuit on the Moon. That’s not the weird part, the weird part is that he’s been dead for 50,000 years. When I first picked up Inherit the Stars, the mystery of how someone ended up on the moon 50,000 years ago was so enthralling that I read the book in a single sitting. I’m not sure if it’s the first time I did that, but it’s the time that sticks in my memory.

I was similarly hooked by the Expeditionary Force series. I didn’t listen to it all in one go, but it was pretty close to that, as you can see by the fact that I’ve already burned through three books (though there are 10-12 more books depending on how you count). I think it’s once again the mystery part that I find so compelling. In this case you’ve got the typical setup of an advanced progenitor race who has mysteriously disappeared, and despite the galaxy crawling with other alien species, the people in the eponymous expeditionary force end up on the forefront of the investigation into what has happened to them. All while trying to fulfill their primary mission of protecting humanity from aliens with vastly superior technology.

Beyond the mystery other positives include: Alanson’s solution to Fermi’s Paradox, and I like his solution to the inevitable tech disparities between humans and aliens, and I really like the world building.

On the negative side, you’re going to need to get really comfortable with deus ex machina because there’s a lot of it. Also there is a certain repetitiveness to things. Imagine it’s a sitcom where each episode has a similar format and each character makes the same kind of jokes in each of those episodes. We’ll see if that begins to get old, but it’s been just the mindless pulpy break I need.

Row Daily, Breathe Deeper, Live Better: A Guide to Moderate Exercise

by: Dustin Ordway

168 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

The advantages of developing a daily rowing habit.

Who should read this book?

If you’re looking for a new low impact exercise, and you’re curious about rowing this is a good introduction.

General Thoughts

I really need to start paying closer attention to a book’s rating before I pick it up. Both this book and the next two have less than 4 stars on Good Reads, which may not sound bad, but given that the average rating appears to be 4 anything less than 4 is below average. This was a perfectly fine book. It assumes the reader has zero rowing experience and if that’s actually the case then it’s a great book. On the other hand if you do have even a little experience, and you don’t need any motivation to row daily, then the book has very little to add to what you probably already know.

Indistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your Life

by: Nir Eyal (A-all)

290 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Making yourself immune to distraction.

Who should read this book?

Those who will read any book on personal improvement no matter how niche. Also anyone who thinks that distractions are ruining their life.

General Thoughts

In some respects the majority of current advice on personal productivity revolves around eliminating distractions, so this is not new territory. Consequently if you’ve already read a lot in this space then much of Eyal’s advice will not be new. Where he does break slightly new ground is in his answer on where the problem lies. Since I’ve already reviewed one book on drugs and I’m about to review another, let’s pretend being distracted is like being addicted.

There are various theories why some people get addicted while others don’t, and why some people can break their addiction while others can’t. Some say it’s genetic, others admit that they’re not sure, and still others say it all has to do with whether a person has a strong network of support, and is generally happy otherwise, that if that’s the case addiction is not a problem. Applying this framework to technological distractions, Eyal is in the latter camp. That being distracted is entirely under our control, and that it’s just a matter of mastering our internal motivations, and being content. I’m not sure if he feels the same way about actual drugs, I just thought the comparison was useful and germane to the post as a whole, because…

Just like I don’t think we should let the Sacklers off the hook (see my first review) I don’t think we should let the tech companies off the hook either. To see why I might say this, let's take one of the stories from the book. This particular story concerns a female professor who got some kind of fitness band which tracked her steps and other activity. The company making the band did everything in their power to “gamify” this device. You could compete with friends, there were daily challenges, there was a point system with rewards and a leaderboard. So one night around midnight, she’s getting ready for bed and it flashes an alert telling her that she can get triple points if she just climbs 20 stairs, which seems so easy that even though she was just about to go to bed she decided to do it, but as soon as she finished it flashed another offer for triple points if she would do another 40 stairs. And then she got yet another offer. I’ll let the book describe what happened next:

For the next two hours—from midnight until two in the morning—the professor treaded up and down her basement staircase as if possessed by some strange mind-controlling power. When she finally did come to a standstill, she realized she had climbed over two thousand stairs. That’s more than the 1,872 required to climb the Empire State Building.

Eyal goes on to explain that this seemingly ridiculous behavior corresponded to an incredibly stressful time in the professor’s life, and that’s why it happened. Eyal’s theory is that all behavior is an attempt to resolve discomfort, and that if she hadn’t had the discomfort of the stress she would have never found herself climbing the Empire State Building in the middle of the night.

Sure that’s obviously part of it, but let’s imagine that she had exactly the same level of stress but without the fitness tracker. I’m guessing that she would have just gone to bed at midnight. And yes, one imagines that she might have tossed and turned for a half hour or even an hour, but she still would have been better off than mindlessly walking the stairs for two hours. The point is that even if discomfort is a necessary element, tech companies prey on this discomfort, and more than that, they amplify create and amplify discomfort as well.

What is a p-value anyway? 34 Stories to Help You Actually Understand Statistics

by: Andrew Vickers

224 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

Statistics and the many ways they can be abused.

Who should read this book?

If you have a basic understanding of statistics and math, and you’re looking to go a little bit deeper this book might be worthwhile.

General Thoughts

I was underwhelmed by this book. For concepts where I did have a pretty good understanding the book was fine, but didn’t add much, and where he was introducing something I hadn’t come across, the book was generally too dry to be engaging. On the latter point, I think the title is misleading. I went in expecting 34 interesting extended metaphors for statistical principles, but instead the “stories” generally consisted of a short self-deprecating joke at the beginning of the chapter—yeah, we get it, you're the cool statistician!—with the remainder of the chapter being more akin to a text book. If I had really been interested in getting into the meat of statistics the book could have been good. But I was looking for something a little lighter.

Additionally, I think Taleb may have permanently turned me against “normal” statistics, and I mean that in a formal sense, as in statistics which focus on a normal/Gaussian/bell curve. As near as I can tell Vickers’ discussion of statistics never really steps outside of assuming some degree of “normality”. The closest he appears to come is in a chapter which describes calculating the “average” salary of everyone in a diner. Most of the time you would use the mean, but if Bill Gates walks in, then the mean becomes meaningless. (Ha! Get it?) Vickers says in that case all you need to do is switch to using the median instead. Which seems to oversimplify the situation to the point of ridiculousness. Taleb would point out that the diner (and the world) have become very different places when billionaires arrive on the scene.

Now, I may be exaggerating a little bit, and as I previously said I wouldn’t claim that I brought my A-game when I read the book, but nowhere in it did I detect any acknowledgement of the difference between what Taleb calls mediocristan and extremistan. A difference that’s very, very important.

The Least of Us: True Tales of America and Hope in the Time of Fentanyl and Meth

by: Sam Quinones

432 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

This is something of a sequel to Quinones’ book Dreamland. (Which I talked about here.) [POST] Dreamland was about OxyContin and heroin, this brings the story to the present day by talking about fentanyl and meth.

Who should read this book?

If you read and enjoyed Dreamland, then I think this is a valuable sequel. If you’re looking for a book on the drug crisis and you’re trying to choose between this book and Dreamland, I would probably recommend Dreamland. This is because without understanding how the crisis started it would be difficult to understand how it got so bad.

General Thoughts

As I mentioned in a previous review it is my intention to do a full post on the current drug crisis. So some of the juicy stuff will have to wait until then, in this space I’m going to talk about homelessness. I’ve been curious about homelessness for a while (here’s a post I did back in 2018) and just based on the number of homeless people I see and encounter, the problem seems to be getting worse. Quinones agrees with this assessment and his book has passages like this:

In 2018, when the Los Angeles Times reported that “L.A.’s Homelessness Surged 75% in Six Years,” this made a lot of sense to Eric Barrera. Those were exactly the years when supplies of Mexican “weirdo” meth really got out of hand. “It all began to change in 2009 and got worse after that,” he told me as we walked through a homeless encampment in Echo Park, west of downtown Los Angeles. “The way I saw myself deteriorating, tripping out and ending up homeless, that’s what I see out here. They’re hallucinating, talking to themselves. Now, it’s people on the street screaming. Terrified by paranoia. These are people who had normal lives.”

The “weirdo” meth is meth made using the P2P method rather than the old method of using ephedrine. We’ll be talking a lot more about weirdo meth in the eventual drug post, but this book makes the argument (as you can tell from the excerpt) that homelessness is increasing and that P2P meth is a major driver of that. And as I said this increase mostly matches my experience, though I was unaware of a possible connection to a change in the way meth was manufactured. But then just in the last few days, Matthew Yglesias was asked whether he thought there was a connection between drug use and homelessness, and he said:

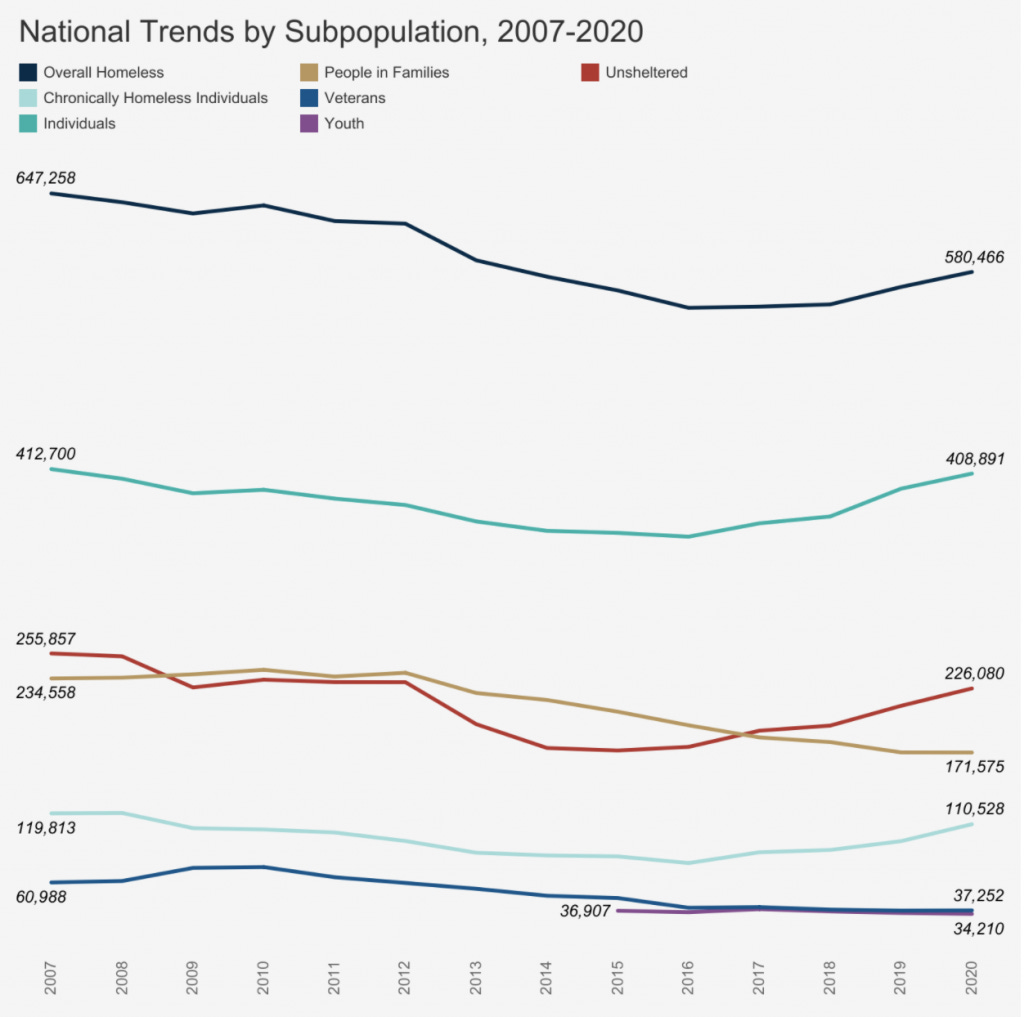

Homelessness fell pretty steadily from 2007-2017 even while the opioid problem was getting worse and worse, so I don’t think the rebound since then can plausibly be attributed to drugs.

And then he provided this graph:

This of course doesn’t match the LA Times statistic Quinones mentions, nor my experience. Nor does Yglesias provide a source for these numbers, nor does he appear to be aware of the meth connection. And he offers all of this up in support of his argument homelessness is primarily driven by a lack of affordable housing. I’ll allow Quinones a chance to retort:

When asked how many of the people he met in those encampments had lost housing due to high rents or health insurance, Eric could not remember one. Meth was the reason they were there and couldn’t leave. Of the hundred or so vets he had brought out of the encampments and into housing, all but three returned.

I’m hoping to be able to get to the bottom of this before I do my post on the drug crisis, but Quinones makes a pretty persuasive case, so for the moment count me as a member of Team Meth. (A phrase I never thought I’d say…)

Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History

by: S. C. Gwynne

384 Pages

Briefly, what was this book about?

The history of the Texan and federal government’s battles against the Comanches.

Who should read this book?

Anyone who’s interested in the history of Texas, or the Indians, or who’s interested in history period.

General Thoughts

I can’t think of many books I’ve seen recommended in more places and by more people than this one. As such I am long overdue for reading it. It was indeed a fantastic book, well written with amazing stories and engaging characters. As such, I would add my recommendation to the others. That said, it wasn’t quite the transcendent experience I was expecting based on the effusive reviews. And it’s possible that I came into the book with impossible expectations, but it’s also possible that at least some of the people reviewing it have not read any other truly great history books, and so when they encountered one it was revelatory. Certainly Empire of the Summer Moon belongs in the category of great history books, it’s just not alone in that category.

As far as the actual content of the book, my favorite chapter was chapter 10 about John Coffee Hays and the creation of the Colt Revolver. The way the US ended up forgetting how to fight the Indians reminded me of the way that we forgot the cure for scurvy (but maybe that’s just me.) Other than that, the book is about what you’d expect, but it gave me new respect and interest for both the history of the Plains Indians and the history of Texas.

Heart: The City Beneath

by: Grant Howitt and Christopher Taylor

220 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

It’s the sourcebook for an independently published role-playing game.

Who should read this book?

If you like Dungeons and Dragons or role-playing in general you’ll probably like this book. The setting is great and the system is inventive.

General Thoughts

It’s been awhile since I reviewed a role-playing sourcebook, which is not to say I haven’t been reading them, just that I normally skim them, as opposed to finishing them (see title of post). Heart was the exception. In part this is because it’s just a great system and beautiful book, but the bigger part is that I’m going to be running a campaign in the setting. The first session was actually this last Saturday. Obviously if I’m going to run it, it’s important to know my stuff. I won’t bore non-gamers out there with any further minutia other than to say that I’m really intrigued by the system, and I look forward to seeing how it plays out in practice.

Should you end up reading and enjoying any of these books let me know. Emails are always appreciated, but of course the best way to let me know you enjoy this stuff is by donating. These books don’t buy themselves.