Eschatologist #13: Antifragility

If you prefer to listen rather than read, this blog is available as a podcast here. Or if you want to listen to just this post:

This newsletter is now a year old, and we spent much of that year working through the ideas of Nassim Nicholas Taleb. This is not merely because I think Taleb is the best guide to understanding the challenges of the modern world, he’s also the best guide to preparing for those challenges.

This preparation is necessary because, as Taleb points out, our material progress has largely come at the expense of increased fragility. This does not necessarily mean that things are more likely to fail in the modern world, just that when they do, such failures come in the form of catastrophic black swans. The deaths and disruptions caused by the pandemic have provided us with an excellent example of just such a catastrophe.

If fragility is the problem, then what’s Taleb’s recommended solution? Antifragility. Upon hearing this word you may think, “Of course, antifragility is the solution to fragility, but what does antifragility even mean?” Fortunately Taleb has a formal definition, but let’s start with his informal definition:

If you have extra cash in the bank (in addition to stockpiles of tradable goods such as cans of Spam and hummus and gold bars in the basement), you don’t need to know with precision which event will cause potential difficulties. It could be a war, a revolution, an earthquake, a recession, an epidemic, a terrorist attack, the secession of the state of New Jersey, anything—you do not need to predict much, unlike those who are in the opposite situation, namely, in debt. Those, because of their fragility, need to predict with more, a lot more, accuracy.

Fragility is when we accept small, limited benefits now, in exchange for potential large, unbounded costs. In the quote it’s the benefit of getting a little extra money by going into debt, which presumably translates into a bigger house or a nicer car but running the risk of bankruptcy if you lose your job and are unable to pay those debts.

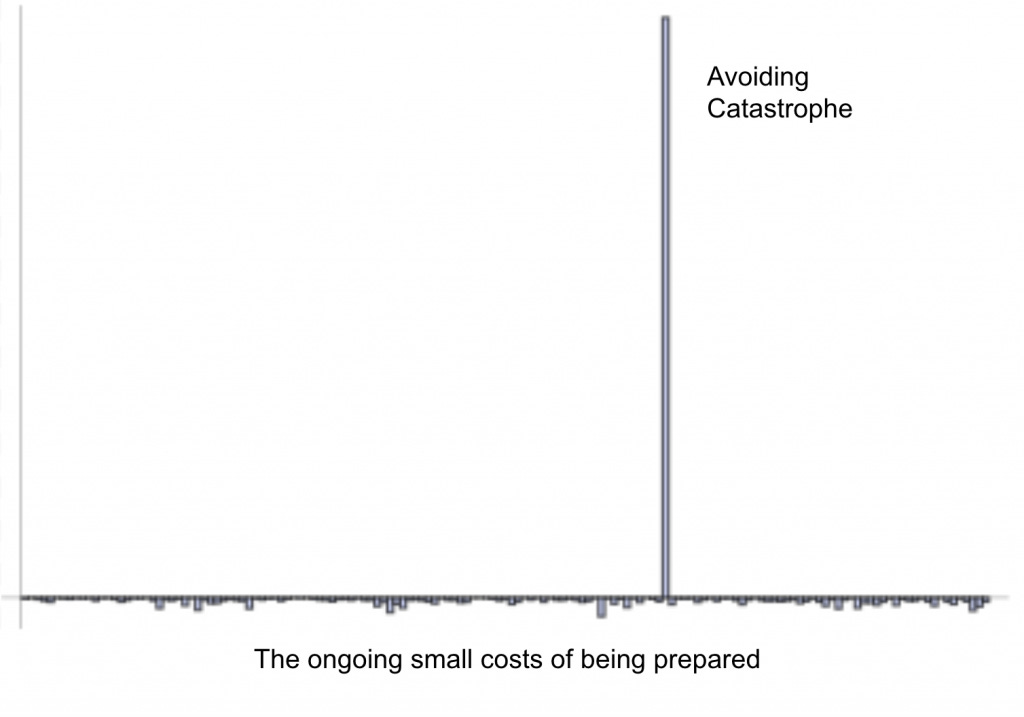

Antifragility is when we accept small, limited costs in exchange for potential large, unbounded benefits. The time and discipline it costs to save money and stockpile spam in your basement—accompanied presumably by a smaller house and a more modest car—turns into a huge benefit when you are unscathed by disaster. As a graph it looks like this:

For fragility just flip the graph upside down. If we apply this to our current catastrophe the pandemic was preceded by thousands of small, fixed benefits, using the time and money we could have spent planning, preparing, and stockpiling, on other things. Things that presumably seemed more important at the time. But these small benefits turned into large costs when the pandemic arrived and revealed how fragile things really were.

The pandemic not only revealed the fragility of our preparations it also revealed the fragility of our logistics when it broke the global supply chain. Of course before the pandemic people didn’t talk about fragility, they talked about efficiency, the wonders of “just in time” manufacturing, the offshoring of production, and global consolidation. But when the black swan arrived all of those things ended up breaking, as fragile things tend to do.

Moving back a little farther in time, the global financial crisis of 2007-2008 is an even better example. As Taleb describes it the entire financial system was focused on picking up pennies in front of a steamroller—limited benefits with eventually fatal consequences.

As you may have already surmised, antifragility is the opposite of all this. It consists of spending a certain amount of time and money on being prepared, some of which will be wasted. Of taking certain risks/costs in order to avoid catastrophic harm. It’s also, like many things, easier said than done. But as long as we’re talking about the pandemic it’s worth asking: what steps are being taken to prepare for the next pandemic?

So far, it’s not looking good, we’ve slashed the amount of money we’re spending on such preparedness, and rather than figuring out the origin of the pandemic (see my last essay) we’re still fighting about masks. I would have hoped that the pandemic would have led us, as a society, to focus more on preparedness, risk management, and above all antifragility, but perhaps not. That being the case, I hope all of my readers are lucky enough to have some gold bars in the basement, even if they’re metaphorical.

All of my gold bars are metaphorical. If you’d like to help make them non-metaphorical consider donating. I understand that it takes a LOT of donations to equal one gold bar, but one has to start somewhere.