Don't Make the Second Mistake

If you prefer to listen rather than read, this blog is available as a podcast here. Or if you want to listen to just this post:

Several years ago, when my oldest son had only been driving for around a year, he set out to take care of some things in an unfamiliar area about 30 minutes north of where we live. Of course he was using Google Maps, and as he neared his destination he realized he was about to miss his turn. Panicking, he immediately cranked the wheel of our van hard to the right, and actually ended up undershooting the turn, running into a curb and popping the front passenger side tire.

He texted me and I explained where the spare was, and then over several other texts I guided him in putting it on. When he was finally done I told him not to take the van on the freeway because the spare wasn’t designed to go over 55. An hour later when he wasn’t home I tried calling him thinking that if he was driving I didn’t want him trying to text. After a couple of rings it went to voicemail, which seemed weird, so after a few minutes I tried texting him. He responded with this message:

I just got in another accident with another driver I’m so so so sorry. I have his license plate number, what else do I need to do?

Obviously my first question was whether he was alright. He said he was and that the van was still drivable (as it turned out, just barely…) He had been trying to get home without using the freeway and had naturally ended up in a part of town he was unfamiliar with. Arriving at an intersection, and already flustered by the blown tire and by how long it was taking, he thought it was a four-way stop, but instead only the street he was on had a stop sign. In his defence, there was a railroad crossing right next to the intersection on the other street, and so everything necessary to stop cross traffic was there, it just wasn’t active. Nor did it act anything like a four way stop.

In any event, after determining that no one else was stopped at what he thought were the other stop signs he proceeded and immediately got hit on the passenger side by someone coming down the other street. As I said the van was drivable, but just barely, and the insurance didn’t end up totaling it, but once again just barely. As it turns out the other driver was in a rental car, and as a side note, being hit by a rental car with full coverage in an accident with no injuries led to the other driver being very chill and understanding about the whole thing, so that was nice. Though I imagine the rental car company got every dime out of our insurance, certainly our rates went up, by a lot.

Another story…

While I was on my LDS mission in the Netherlands, my Dad wrote to me and related the following incident. He had been called over to my Uncle’s house to help him repair a snowmobile (in those days snowmobiles spent at least as much time being fixed as being ridden). As part of the repair they ended up needing to do some welding, but my dad only had his oxy acetylene setup with him. What he really needed was his arc welder, but that would mean towing the snowmobile trailer all the way back to his house on the other side of town, which seemed like a lot of effort for a fairly simple weld. He just needed to reattach something to the bulkhead.

In order to do this with an oxy acetylene welder you had to put enough heat into the steel for it to start melting. Unfortunately on the other side of the bulkhead was the gas line to the carburetor, and as it started absorbing heat the line melted and gasoline poured out on to the hot steel immediately catching on fire.

With a continual stream of gasoline pouring onto the fire, panic ensued, but it quickly became apparent that they needed to get the snowmobile out of the garage to keep the house from catching on fire. So my Father and Uncle grabbed the trailer and began to drag it into the driveway. Unfortunately the welder was still on the trailer, and it was pulling on the welding cart which had, among other things, a tank full of pure oxygen. My Dad saw this and tried to get my Uncle to stop, but he was far too focused on the fire to pay attention to my Father’s warnings, and so the tank tipped over.

You may not initially understand why this is so bad. Well, when an oxygen tank falls over the valve can snap off. In fact when you’re not using them there’s a special attachment you screw on to cover the valve which doesn’t prevent it from snapping off, but prevents it from becoming a missile if it does. Because, that’s what happens, the pressurized gas turns the big metal cylinder into a giant and very dangerous missile. But beyond that it would have filled the garage they were working in, the garage that already had a significant gasoline fire going with pure oxygen. Whether the fuel air bomb thus created would have been worse or better than the missile which had been created at the same time is hard to say, but both would have been really bad.

Fortunately the valve didn’t snap off, and they were able to get the snowmobile out into the driveway where a man passing by jumped out of his car with a fire extinguisher and put out the blaze. At which point my Father towed the trailer with the snowmobile over to his house, got out his arc welder, and had the weld done in about 30 seconds of actual welding.

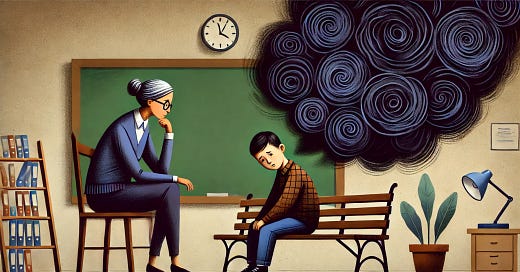

What do both of these stories have in common? The panic, haste, and unfamiliar situation caused by making one mistake directly led to making more mistakes, and in both cases the mistakes which followed ended up being worse than the original mistake. Anyone, upon surveying the current scene would agree that mistakes have been made recently. Mistakes that have led to panic, hasty decisions, and most of all put us in very unfamiliar situations. When this happens people are likely to make additional mistakes, and this is true not only for individuals at intersections, and small groups working in garages, but also true at the level of nations, whether those nations are battling pandemics or responding to a particularly egregious example of police brutality or both at the same time.

If everyone acknowledges that mistakes have been made (which I think is indisputable) and further grants that the chaos caused by an initial mistake makes further mistakes more likely (less indisputable, but still largely unobjectionable I would assume). Where does that leave us? Saying that further mistakes are going to happen is straightforward enough, but it’s still a long way from that to identifying those mistakes before we make them, and farther still from identifying the mistakes to actually preventing them, since the power to prevent has to overlap with the insight to identify, which is, unfortunately, rarely the case.

As you might imagine, I am probably not in a position to do much to prevent further mistakes. But you might at least hope that I could lend a hand in identifying them. I will do some of that, but this post, including the two stories I led with, is going to be more about pointing out that such mistakes are almost certainly going to happen, and our best strategy might be to ensure that such mistakes are not catastrophic. If actions were obviously mistakes we wouldn’t take those actions, we only take them because in advance they seem like good ideas. Accordingly this post is about lessening the chance that seemingly good actions will end up being mistakes later, and if they do end up being mistakes, making sure that they’re manageable mistakes rather than catastrophic mistakes. How do we do that?

The first principle I want to put forward is identifying the unknowns. Another way of framing this is asking, “What’s the worst that could happen?” Let me offer two competing examples drawn from current events:

First, masks: Imagine, if, to take an example from a previous post, the US had had a 30 day stockpile of masks for everyone in America, and when the pandemic broke out it had made them available and strongly recommended that people wear them. What’s the worst that could have happened? I’m struggling to come up with anything. I imagine that we might have seen some reaction from hardcore libertarians despite the fact that it was a recommendation, not a requirement. But the worst case is at best mild social unrest, and probably nothing at all.

Next, defunding the police: Now imagine that Minneapolis goes ahead with it’s plan to defund the police, what’s the worst that could happen there? I pick on Steven Pinker a lot, but maybe I can make it up to him a little bit by including a quote of his that has been making the rounds recently:

As a young teenager in proudly peaceable Canada during the romantic 1960s, I was a true believer in Bakunin's anarchism. I laughed off my parents' argument that if the government ever laid down its arms all hell would break loose. Our competing predictions were put to the test at 8:00 a.m. on October 7, 1969, when the Montreal police went on strike. By 11:20 am, the first bank was robbed. By noon, most of the downtown stores were closed because of looting. Within a few more hours, taxi drivers burned down the garage of a limousine service that competed with them for airport customers, a rooftop sniper killed a provincial police officer, rioters broke into several hotels and restaurants, and a doctor slew a burglar in his suburban home. By the end of the day, six banks had been robbed, a hundred shops had been looted, twelve fires had been set, forty carloads of storefront glass had been broken, and three million dollars in property damage had been inflicted, before city authorities had to call in the army and, of course, the Mounties to restore order. This decisive empirical test left my politics in tatters (and offered a foretaste of life as a scientist).

Now recall this is just the worst case, I am not saying this is what will happen, in fact I would be surprised if it did, particularly over such a short period. Also, I am not even saying that I’m positive defunding the police is a bad idea. It’s definitely not what I would do, but there’s certainly some chance that it might be an improvement on what we’re currently doing. But just as there’s some chance it might be better, one has to acknowledge that there’s also some chance that it might be worse. Which takes me to the second point.

If something might be a mistake it would be good if we don’t end up all making the same mistake. I’m fine if Minneapolis wants to take the lead on figuring out what it means to defund the police. In fact from the perspective of social science I’m excited about the experiment. I would be far less excited if every municipality decides to do it at the same time. Accordingly my second point is, knowing some of the actions we’re going to take in the wake of an initial mistake are likely to be further mistakes we should avoid all taking the same actions, for fear we all land on an action which turns out to be a further mistake.

I’ve already made this point as far as police violence goes, but we can also see it with masks. For reasons that still leave me baffled the CDC had a policy minimizing masks going all the way back to 2009. But fortunately this was not the case in Southeast Asia, and during the pandemic we got to see how the countries where mask wearing was ubiquitous fared, as it turned out, pretty well. No imagine that the same bad advice had been the standard worldwide. Would it have taken us longer to figure out that masks worked well for protecting against COVID-19? Almost certainly.

So the two rules I have for avoiding the “second mistake” are:

Consider the worst case scenario of an action before you take it. In particular try to consider the decision in the absence of the first mistake. Or what the decision might look like with the benefit of hindsight. (One clever mind hack I came across asks you to act as if you’ve been sent back in time to fix a horrible mistake, you just don’t know what the mistake was.)

Avoid having everyone take the same response to the initial mistake. It’s easy in the panic and haste caused by the initial mistake for everyone to default to the same response, but that just makes the initial mistake that much worse if everyone panics into making the same wrong decision.

There are other guidelines as well, and I’ll be discussing some of them in my next post, but these two represent an easy starting point.

Finally, I know I’ve already provided a couple of examples, but there are obviously lots of other recent actions which could be taken or have been taken and you may be wondering what their mistake potential is. To be clear I’m not saying that any of these actions are a mistake, identifying mistakes in advance is really hard, I’m just going to look at them with respect to the standards above.

Let’s start with actions which have been taken or might be taken with respect to the pandemic.

Rescue package: In response to the pandemic, the US passed a massive aid/spending bill. Adding quite a bit to a national debt that is already quite large. I have maintained for a while that the worst case scenario here is pretty bad. (The arguments around this are fairly deep, with the leading counter argument being that we don’t have to worry because such a failure is impossible.) Additionally while many governments did the same thing, I’m less worried here about doing the same thing everyone else did and more worried about doing the same thing we always do when panic ensues. That is, throw money at things.

Closing things down/Opening them back up: Both actions seemed to happen quite suddenly and in near unison, with the majority of states doing both nearly simultaneously. I’ve already talked about how there seemed to be very little discussion of the economic effects in pre-pandemic planning and equally not much consideration for what to do in the event of a new outbreak after opening things back up. As far as everyone doing the same thing, as I’ve mentioned before I’m glad that Sweden didn’t shut things down, just like I’d be happy to see Minneapolis try a new path with the police.

Social unrest: I first had the idea for this post before George Floyd’s death. And at the time it already seemed that people were using COVID as an excuse to further stoke political divisions. That rather than showing forth understanding to those who were harmed by the shutdown they were hurling criticisms. To be clear the worst case scenario on this tactic is a 2nd civil war. Also, not only is everyone making the same mistake of blaming the other side, but similar to spending it also seems to be our go-to tactic these days.

Moving on to the protests and the anger over police brutality:

The protests themselves: This is another area where the worst case scenario is pretty bad. While we’ve had good luck recently with protests generally fizzling out before anything truly extreme happened, historically there have been lots of times where protests just kept getting bigger and bigger until governments were overthrown, cities burned and thousands died. Also while there have been some exceptions, it’s been remarkable how even worldwide everyone is doing the same thing, gathering downtown in big cities and protesting, and further how the protests all look very similar, with the police confrontations, the tearing down of statues, the yelling, etc.

The pandemic: I try to be pretty even keeled about things, and it’s an open question whether I actually succeed, but the hypocrisy demonstrated by how quickly media and scientists changed their recommendations when the protests went from being anti-lockdown to anti police brutality was truly amazing both in how blatant and how partisan it was. Clearly there is a danger that the protests will contribute significantly to an increase in COVID cases, and it is difficult to see how arguments about the ability to do things virtually don’t apply here. Certainly whatever damage has been caused as a side effect of the protests would be far less if they had been conducted virtually…

Defunding the police: While this has already been touched on, the worst case scenario not only appears to be pretty bad, but very likely to occur as well. In particular everything I’ve seen since things started seems to indicate that the solution is to spend more money on policing rather than less. And yet nearly in lock stop most large cities have put forward plans to spend less money on the police.

I confess that these observations are less hard and fast and certainly less scientific than I would have liked. But if it was easy to know how we would end up making the second mistake we wouldn’t make it. Certainly if my son had known the danger of that particular intersection he would have spent the time necessary to figure out it wasn’t a four way stop. Or if my father had known that using the oxy acetylene welder would catch the fuel on fire he would have taken the extra time to move things to his house so he could use the arc welder. And I am certain that when we look back on how we handled the pandemic and the protests that there will be things that turned out to be obvious mistakes. Mistakes which we wish we had avoided. But maybe, if we can be just a little bit wiser and a little less panicky, we can avoid making the second mistake.

It’s possible that you think it was a mistake to read this post, hopefully not, but if it was then I’m going to engage in my own hypocrisy and ask you to, this one time, make a second mistake and donate. To be fair the worst case scenario is not too bad, and everyone is definitely not doing it.